In some ways greater Lansing is still thawing from the natural disaster “event” Dec. 21 that left 40,000 residents and businesses cold and dark.

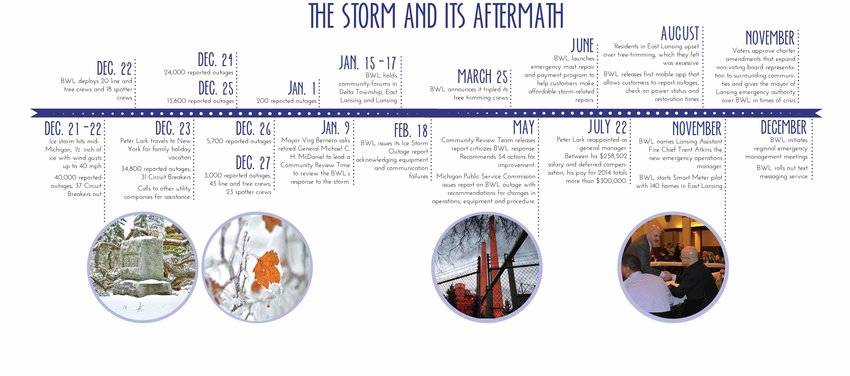

That “event” wasn’t the Gemini winter storm that encased the community in a half inch of ice or the power outages it caused, but the firestorm of anger, distrust, frustration and disbelief that followed as the public utility fumbled executing and communicating the restoration, which took up to 10 days for some. Board of Water & Light General Manager Peter Lark was harshly criticized for leaving for New York City on Dec. 22 at the height of the crisis; for deleting internal emails that documented his communications about the restoration process; and for the utility’s overall lack of communication with the public and perceived lack of empathy.

The storm forever changed not only the BWL but the entire community, how we relate to one another and what our expectations are.

BWL isn't a conventional commercial utility. It is owned by the people of Lansing, a relationship captured by its motto: “Hometown People. Hometown Power.” BWL is — or was — a big family business, different from profit-making energy giants like Consumers Energy or DTE. The dismal performance a year ago was a betrayal, an infidelity of sorts, fraying the warm blanket of trust the city expected of its power company.

The larger Lansing family is still dealing with the breakdown. There are lots of patches — many of them skillfully tailored. But with winter approaching the uncertainty remains. Too little time has passed.

“From a utility process we’re improved,” said BWL Commissioner Cynthia Ward, the only board member to vote not to reappoint Lark as manager. “In emergency preparedness, there’s improvement. In my own household preparedness, there’s improvements. It forced a lot of people to think about things. ... We have to be a better community for it even if everyone is individually better prepared.”

The BWL has adopted a long list of changes suggested by the independent Community Review Team and the Michigan Public Service Commission. There’s an emergency operations manager, a new mobile app, new text message service. There’s a social media manager and representation on the board of commissioners from surrounding communities will begin in July.

READ: GEN. MCDANIEL: BWL and City of Lansing must develop community resilience

READ: Remembering the ice storm

The utility promises better communication in the future.

Retired General Michael McDaniel, who headed the review team and a homeland security expert, said the utility has made good on a lot of changes, but more is left to be done.

“The one area of criticism is that there needs to be even more community engagement,” McDaniel said. “BWL is going to roll their eyes and say, ‘McDaniel we’re doing community engagement.’ They’re absolutely right, but they need even more of it.”

Communication and cultureIn a phone interview, Lark highlighted the changes that have been made in the past year, including the Outage Center phone number, “the mobile app, Nixle alerts, emergency operations manager, social media specialist … more line crews … tree trimming crews … in short we are ready.”

The storm created a record outage of 40,000 — double it’s prior largest single outage, according to the BWL’s storm outage report. It was unable to handle the volume of calls. Email queues hit their limit. The utility acknowledged not having a crisis communication plan.

The immediate aftermath was a collision with community, rather than collaboration. Lark gave optimistic restoration times rather than realistic ones, McDaniel said.

“Every time you make a promise you’ve gotta either keep that promise or you’ve got to get back up there and say why you didn’t keep that promise,” McDaniel said. “You have to stand up every day and say this is where we are.”

Long nights, angry public meetings and charged statements framed the dark January and February days that followed as the community worked to understand the problems that led to the prolonged outage and how to prevent one like it in the future.

“If this storm has revealed one thing to the public is that there is a cultural problem in the upper management levels of BWL,” said Ryan Sebolt, at a committee of the whole meeting Feb. 18. “It’s a culture of superiority and arrogance.”

The public created a crowd-sourced Google map of outages and restorations to provide information they felt wasn’t being supplied by the utility.

A mock BWL Twitter account took jabs at the utility, making fun of its missteps.

The BWL is still a favorite punching bag in barstool conversation.

Many called for Lark’s ouster, but he was reappointed as general manager in June. He earns a $258,502 salary and deferred compensation, giving him a total annual pay of more than $300,000.

“I don’t believe the BWL behaved arrogantly,” Lark said when asked if Sebolt’s comment in the February meeting was accurate or fair.

“We are a completely different BWL than we were in the past,” Lark said. “We are aggressively going out to see our customers.”

And when asked if the community has forgiven BWL today he replied: “I don’t know about forgiveness or that we are looking for forgiveness, but community acceptance of the BWL.”

The trust will be earned in a real-life test, McDaniel said.

“How does the Board of Water & Light build back the trust? There’s going to be another event. ... It’s going to be based on their ability to respond to that event.”

Mayor Virg Bernero said he applauds the BWL for the changes that have been put in place and “an exercise in being self critical.”

“I think for most people they simply would like to know that it won’t happen again,” Bernero said. “That would be the greatest apology they could get. I wish we could provide that guarantee. But with the reality of weather patterns and the uncertainty of the grid I doubt anyone could give that guarantee.”

RegionalismThe response to the storm, not only by the utility but the municipalities, spotlighted a need to collaborate, Bernero said.

“This was a very potent reminder to us that weather-related emergencies are spread widely through the region,” he said. “They’re not compartmentalized to one municipality. We should be looking to pool our resources.”

Last month the BWL named Trent Atkins to be the new emergency operations manager for the utility. He was formerly assistant fire chief in the Lansing Fire Department.

“With Trent moving to the Board of Water & Light, he can help all of the region to take a more cohesive approach to emergency response.”

Atkins led the first regional emergency response meeting at the beginning of the month. The goal is to have surrounding communities share their emergency response plans, find duplication, opportunities to share. That means sharing their playbook so to speak.

Can they do it?

“I hope so. It’s up to them to do it,” McDaniel said.

“There’s no question we need closer regional collaboration,” McDaniel said. “The debate is going to be on how we achieve that. There’s clearly resistance to the idea of having a regional emergency operations center because everybody wants to have their own.

That’s fine as long as they are so well connected that they are like nodes on a single network. They have to be. Or else we will see inconsistencies in response across the region.”

Planning is one thing, McDaniel said. Putting a plan into action under stress, like a once-in-a-lifetime storm, is another.

“An event like that truly did stress staff and plan to the breaking point,” McDaniel said. “One of the things we don’t know yet has changed, but we assume has, is that there was no true documentation. Nobody was keeping records.”

McDaniel said he wrote a note to himself on his CRT report: “No documentation means no lessons, no lessons learned equals no learning.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here