It was an intimate space chock full of acoustic music, social and political debate and palpable change. It was spaces like these, which emerged in the '60s, that gave singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez their starts.

By 1974 it was common to take a ride to the Ark in Ann Arbor for your “folk fix.” The only place where you could find a folk jam locally at that time was in the then-new Elderly Instruments on Grand River in East Lansing. That all changed in 1975 with the birth of a concert series inspired by a need for affordable, good folk music.

“We were just hoping to kind of snag folk singers on the way between Ann Arbor and Chicago to come do a concert for us,” said Bob Blackman, a longtime leader of the local folk community. “I don’t think we ever envisioned it would go on for more than a few years.”

The Ten Pound Fiddle is 40 this year. The concert series was created much like a folk song comes together. It is both a personal and a community endeavor. The parts are simple and the feeling is deep.

The Fiddle is a nonprofit music series that also hosts dances and singalongs. Unlike most concert venues, the Fiddle doesn’t have a physical home. Its concerts float from location to location.

It’s a format that has allowed the organization to keep costs down, pay artists well and grow a folk music community. The board members along with an army of nearly 70 volunteers produce around 30 concerts and 10 dances every year. It has a paid membership of more than 300.

Over the years the series has drawn such acts as Tom Paxton, Janis Ian, Utah Phillips, The Chenille Sisters, and Suzanne Vega, and this March Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul & Mary).

“The Ten Pound Fiddle is one of the pre-eminent clubs in the country,” said Sally Rogers, a nationally known folk singer who got her start with the Fiddle. “It is on every traveling folk musician’s list of places they have played or would like to play. ”

Arising from the actions of a few folk music fans who saw that something was missing in East Lansing, the Fiddle came from humble but ambitious beginnings in the fall of 1974. At the time folk music lovers would hang out in Elderly Instruments checking out the used acoustic guitars, banjos, dulcimers and mandolins. Blackman, a 1970 East Lansing High School graduate, spent his first three years at Kalamazoo College managing the Black Spot, the student coffee house there. He returned to East Lansing, attending Michigan State University for his fourth year of college.

“I met some people who were interested in starting a coffee house here,” he said, “and ran into Gary and Barb Gardner, who had moved here from Boston ... and had been very active in the folk scene there.”

Gary Gardner and Blackman revived the dormant MSU Folksong Society to gain access to a free venue on campus. They would begin to produce what would be known as the Ten Pound Fiddle concert series.

Named for an old Scottish fiddle tune, the Ten Pound Fiddle would follow a British folk club format for its concerts. A group of local “resident singers” would open the show, followed by a set with the main act for the first half. Then, following the intermission, an open mic session featuring “floor singers” from the audience would lead up to the main act’s second set. It was inclusive, simple and organic.

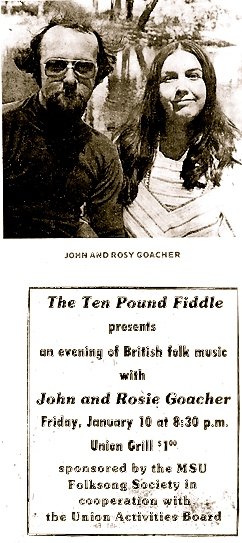

The Fiddle’s first concert was Jan. 10, 1975, at the MSU Union Grill in a small room called Old College Hall. The main act was John and Rosy Goacher, performing an evening of British folk music. John was the Lancashire, England-born host of WKAR Radio’s A British Tradition, and Rosy, a Lansing native. The resident singers were Elderly Instrument founder Stan Werbin, Blackman, then MSU music therapy major and Elderly Instrument employee Sally Rogers, and Gardner. More than 100 people attended the show, joining in on the choruses of “The Wild Rover,” and “Red-Haired Mary,” among others.

Another concert followed the next Friday, featuring Joel Mabus, who has since become a Fiddle favorite in addition to having recorded more than 20 albums, and penning a banjo tune, Firelake, familiar to many folk enthusiasts nationwide as theme music for NPR’s syndicated show The Folk Sampler.

Rogers, a Connecticut-based singer, songwriter, and dulcimer player who has gone on to release 13 albums, learned a lot in the Fiddle’s early days.

“We had so many fine musicians living within 30 minutes of town: Joel Mabus, Ray Kamalay, Kitty Donohoe, Karrie Potter, Dave and Mike Ross, the Lost World Stringband, etc., etc., etc,” Rogers said. “There was no shortage of really good musicians.”

Rogers served for several years as the Fiddle’s booking manager.

“I helped arrange for Jean Ritchie to come to the Fiddle,” Rogers said. “She also did a dulcimer workshop. She was and is my idol and mentor.”

Rogers was also coming to realize just how friendly and supportive the folk community could be.

“I'll never forget how full of song and laughter she and her husband, George, were,” she said. “They were like family, and [we] became close friends. George produced and was the videographer of my one and only children's video.

Defined by the American Heritage Dictionary, folk music is “music originating among the common people of a nation or region and spread about or passed down orally, often with considerable variation.”

Folk musicians and folk music lovers are plain folk. Artists often stay at the homes of volunteers rather than in hotels. Early concerts were in people’s homes, and “house concerts” are still a staple for emerging folk musicians to make their way.

The experience isn’t one-way. Fiddle audiences and performers interact intimately even during the shows.

“The audiences make the club,” Rogers said. “It is known as a singing club.”

That’s the nature of folk music though.

“What folk music is really about historically is people who are just singing for their own entertainment because they can’t afford to go to concerts,” Blackman said. “Or they can’t afford to buy a lot of recordings. ...It wasn’t so much that you did songs that were old, it’s that you did songs that you knew. ...Whatever songs they heard or knew wherever they came from, they just like to sing them with their friends and family for their own amusement. That, to me, is the core of what folk music is about.”

Community singsEven though the Fiddle is known as a singing club on the national folk scene, it wasn’t until it had been around for over 20 years that it began producing an annual event dedicated to audience involvement.

The Fiddle’s current booking manager, Sally Potter, and her band Second Opinion once played Pete Seeger’s Clearwater Festival on the Hudson River, a festival drawing tens of thousands of folk fans annually.

One of the festival’s seven stages was a singing tent, where every hour on the hour, songleaders would lead the audience in song.

“We had our shift in the middle of Saturday,” Potter said, “and there were four women in the front row, and I’d seen them there Thursday, Friday and Saturday morning. I said to them, ‘you know, Sweet Honey in the Rock is here, (Tom) Paxton is here ...people are here! And you’ve been here all weekend!’ They looked up and said, ‘Well, yeah, this is singing! Isn’t this what a folk festival is?’”

Potter saw this same enthusiasm at local concerts and realized the potential for the Ten Pound Fiddle.

“Instead of a festival where everyone’s just listening to everyone performing,” she thought, “where, very often there’s this wall between the performer and the audience, why don’t we just have one where song leaders pick the songs, we give everybody the words and we just start singing?”

The first Mid-Winter Singing Festival was at the Hannah Community Center in February 2003, with sings in the auditorium on Friday and Saturday evenings, and workshops on Saturday afternoon.

“I think it’s been a big shot in the arm for the Ten Pound Fiddle,” Blackman said about the community sings, “and for the Great Lakes Folk Festival, where (Potter has also done) this wonderful community sing for the last few years. It really brings the Fiddle back to some of those early roots; people doing not necessarily traditional songs, but songs that everybody knows in a group format, as opposed to ‘I am a performer, I am doing songs that I have written; and you are sitting in the audience listening,’ which had sort of become the dominant notion of what folk music was all about in terms of performance. So I’m really happy to see that.”

More than a songThe Ten Pound Fiddle isn’t only about songs and singing. In 1976, Bob Stein moved to East Lansing from Boston, bringing with him over 30 years of experience in and a passion for contra dance, a form of traditional folk dance similar to square dancing, led by a caller. Having seen a column by Blackman about the Fiddle in Sing Out! Magazine, a national folk music magazine, Stein made sure to look them up soon after he arrived.

At that time, there were only a couple of small contra dances in Detroit and Ann Arbor, neither of which were very well attended, as well as some traditional square dances in Webberville and Dimondale, which were waning in popularity. So, with the assistance of the Fiddle volunteers, the first Ten Pound Fiddle contra dance was held in the MSU ballroom in 1977. The Fiddle dances drew around 200 people from around the state in the early years, and more clubs gradually formed in Michigan, which now boasts around 20 dances monthly.

Stein’s wife, Laura, who joined him in East Lansing two years later, took a job at Elderly Instruments. Soon after that, Bob convinced her to use her talent at the piano and form a band to play the dances. Joel Mabus was teaching guitar at Elderly, so Laura approached him about playing in the newly formed band. As it turned out, he was learning the fiddle and was happy to have the opportunity to play solo fiddle along with Laura’s piano, and a banjo player.

Over the years, the Steins have remained closely involved in the Fiddle, not only doing the contra dances, but also taking up the tradition of housing visiting musicians Rogers had been hosting until she moved away, and the post-concert gatherings that took place in the earlier years, “when the performers were young,” Laura Stein said. “Now, they’re all too tired after gigging all over the place, so we just feed them quietly.”

The dances, now on the first Saturday of the month at Lansing’s Central United Methodist Church, draw all ages.

“It’s fun,” Laura Stein said. “People who have any kind of interest in it should show up. There are lessons before the dance. Just pick the best dancer on the floor, ask that person, male or female, to dance with you, and you’ll have a good time and you’ll learn how to do it.”

Several years ago, a group of contra dance enthusiasts who didn’t think one dance a month was enough formed the Looking Glass Music and Arts Association. Looking Glass holds dances on the third Saturday of the month, also at Central United Methodist Church, and shares many members with the Fiddle. The two groups celebrate New Year’s Eve every year with a potluck and contra dance at the church.

40 years is a long timeSo, how does an all-volunteer organization manage to remain relevant and successful for four decades?

“I think the secret is that it’s never been a one-person show,” Bob Stein said. “So the people that are doing the organizing have continually changed. As people got tired, new people came in, and it wasn’t all at once. So there’s this continuity. People like Bob Blackman, who have been along the whole time kind of help with the history, as I have. Even if we weren’t actively involved in organizing, there’s still some institutional memory here.”

With no permanent home, the Fiddle can also size its venue to fit the act, offering flexibility in both budget and intimacy. The Fiddle can bring high quality traditional acts that have a smaller following without the worry that ticket sales won’t support the venue, but will offer the artist a full house of fans who know and love their music.

Without the overhead costs of a bricks and mortar, the board members can focus on their roles, which support the production of concerts and dances, rather than raising funds for overhead operating expenses. Early on, the Fiddle’s board determined that the best way to support itself was to offer the artist a guaranteed amount, plus a percentage of the gate remaining after expenses were paid.

This simple, common-sense approach, along with membership fees being used for improvements such as a website and sound equipment upgrades within the organization, have served to keep it viable.

But maybe, when it comes right down to it, it’s because it’s a folk music organization.

“The whole folk music movement has always been based on community efforts and volunteers,” Blackman said, “and since the heyday in the ‘60s when folk acts were playing huge venues, it’s really gone way back down to the communal community level, and that’s really where it still exists: in house concerts, small venues and churches, and on college campuses. In folk radio and folk festivals it’s often the same. It’s folk people who are passionate about it, who will devote time and energy to it.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here