Officials at the Lansing Board of Water & Light started hunting last week for two Lansing residents to serve on an advisory committee that is charged with brainstorming new electricity-generation options as its nearly 60-year-old coal-fired power plants heads toward decommission in four years or less.

The two volunteers will serve on a committee with seven other experts, all of whom BWL will announce next month. They will make recommendations that influence the fate and price of the city and nearby communities' electricity, after Lansing shutters the Eckert power plant amid tighter environmental regulations and the challenge of running an aging plant on a floodplain.

Neither BWL nor the city has released specific details that could answer lingering questions about Lansing’s post-Eckert power dilemma: What that replacement would be, or how much it might cost, and what it means for ratepayers.

That’s all up to the committee, said BWL spokesman Stephen Serkaian.

“Essentially the options include building a new replacement plant, buying energy off of the grid, or increased use of renewable energy like solar and wind,” Serkaian said.

The BWL is looking for what it calls a “diverse” group of people to decide which of those options the utility will end up going with.

According to a statement from the BWL, the volunteers are being pulled from various sectors to form a committee that has a collective “knowledge of the energy industry, the region’s power needs and experience as BWL customers.”

Together, they’ll lead seven public meetings stretching from October to February. After that, committee members will present their recommendation for replacing the power that Eckert generates. (Applications from those interested in serving should be submitted to the BWL by today.)

An Aging Plant and New Regulations

As power plants age, they become costlier and less efficient, said Joe Nipper, a spokesman for the American Public Power Association, which represents about 2,000 municipal power plants (including Eckert) across the country. About 35 percent of the power these municipal plants produce comes from coal-fired facilities, many of them aging.

“It becomes more costly to maintain, you find it difficult to find parts, etc.,” Nipper said.

At the Eckert station, for example, Serkaian said the utility finds it difficult to locate spare parts for the generator and boiler units, in particular.

But Nipper said a well-maintained power plant can keep running for a long time.

And many of them do, especially considering the economic incentive for communities to keep them producing at least as long as it takes to recoup the cost of the municipal bonds that most public bodies issue to raise the capital for constructing a power plant, Nipper said.

Eckert pumps out about 69 percent of the power that it did in its heyday. The six coal-powered electric-generating units once supplied about 420 megawatts of power, according to city documents. Now, it’s capable of a 290-megawatt output.

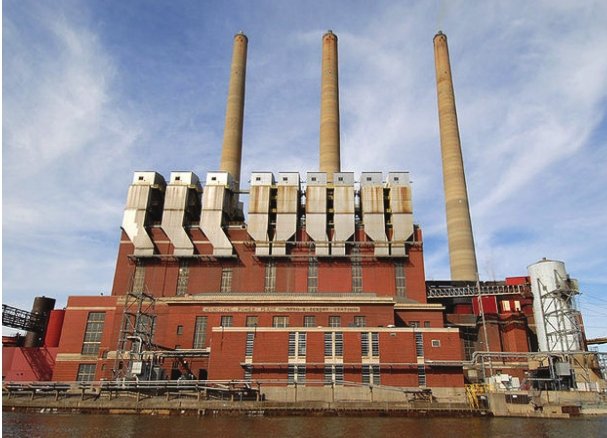

The power station — which has three smokestacks locally known as Wynken, Blynken and Nod — supplied power to Lansing as early as the 1920s.

Eckert was upgraded in the 1950s and 1970s, when the Erickson plant, which produces 156 megawatts of power, was also constructed. Most of the city’s electric assets have been the same ones Lansing has used for more than four decades, according to city documents.

Eckert still supplies power to portions of the city that Lansing officials consider critical, like one-third of the power that downtown Lansing and the surrounding area use. That includes power that goes to the General Motors Lansing Grand River Plant.

“Without electrical generation at Eckert, downtown Lansing is one contingency from failure,” the meeting minutes from an August BWL Board of Commissioners’ meeting said.

According to the same minutes, finding a replacement for the power that Eckert generates will mean an “unprecedented level of work for the next seven to 10 years,” posing “a challenge to human resources.”

Lansing isn’t the only city facing the challenges of generating power from old plants.

By 2020, 25 other coal units in the state will be retired too, Valerie Brader, the executive director of the Michigan Agency for Energy, told a Senate committee on Thursday.

Those plants are slated for decommission regardless of whether new proposed regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency become codified; those proposed regulations would dramatically slash the amount of carbon dioxide that power-generation stations can pump into the atmosphere.

Environmentalists and many Democrats lauded the regulations as a step toward seriously combating climate change.

The pending clean air regulation would limit the amount of carbon dioxide — a major greenhouse gas — plants like Eckert can shoot into the atmosphere.

But many conservatives are critical because they say it would end up increasing operation costs as plants are either forced to install new parts to mitigate pollution or shut down completely.

Officials at BWL say other new environmental regulations are partly to blame for the scheduled Eckert closure, though its age and the fact that it’s located on a 100-year-floodplain are also significant factors.

“Reasons (for the decommission) included the changing landscape of federal and state coal regulations, difficulty in maintaining a plant that is nearly 60 years old and because the plant is located in a 100-year floodplain,” Serkaian said.

Photo by Paul R. Kucher.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here