To be thrown into an identity crisis at the age of 3 is a little early, but that’s what is happening to MSU’s Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum as it nears its third birthday, coming in November.

The death of the Broad’s founding director, Michael Rush, in March robbed the museum of a passionate and unorthodox guiding spirit. The blue-ribbon staff Rush assembled in 2012 has scattered to the other cities and jobs, leading to turnover in every top position.

An international search committee will soon meet to start the process of choosing a new director, according to MSU.

Staff attrition isn’t the only problem facing the Broad: Attendance has fallen short of first expectations. According to Whitney Stoepel, Broad Museum director of public relations, the museum attracted 108,356 visitors in its first year and 59,894 in its second year. It expects to top 60,000 in its third year, with about 52,000 visitors so far.

While that means that tens of thousands of people are taking the plunge into contemporary art, the numbers are well below the 150,000 visitors per year predicted in a study by the Anderson Economic Group, commissioned by MSU in 2012.

The visitors have come from 80 countries, and many of the exhibits have got ten attention from national and international art world. The museum, or at least its coffee shop, is also catching on as a student hangout, as MSU hoped. But there is little evidence that the Broad has been embraced by a broader mid-Michigan community at the level its founders had hoped.

With a new director on the horizon and a new curator, Caitlín Doherty, in place, the Broad is clearly at a crossroads, its tender age notwithstanding.

Life without Rush

Broad Museum staff members past and present say it’s impossible to overstate the hole Rush left when he died of pancreatic cancer.

Former curator Alison Gass said Rush’s commitment to the Broad “prolonged his life.”

“He loved that museum,” Gass said. “He lived so much longer than anyone could have imagined with his diagnosis.”

“I traveled halfway around the world to work with Michael Rush,” Doherty said.

Graham Beal, director of the Detroit Institute of Arts for 16 years until he stepped down in June, was on the search committee that chose Rush and will help choose his successor.

“We were very, very lucky to have a candidate of (Rush’s) caliber, for a museum that had yet to establish itself,” Beal said.

Joseph Rosa, former curator of archi tecture and design at the Art Institute of Chicago and now director of the University of Michigan Museum of Art, made the same point at Rush’s memorial.

“You have people that, honestly, should have gone to New York, L.A. or Chicago, but they came here because of Michael,” Rosa said. “So in many ways, his legacy has been established.”

But a legacy built of people is ephemeral. Gass, the Broad’s ebullient first curator and Rush’s closest collaborator, left for an administrative post at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center in June. Gass said she made the move to be closer to her family and her native Bay Area.

Min Jung Kim, who started at the Broad as deputy director in 2012, left the museum last month to become the director of the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut.

Tammy Fortin, the curatorial program manager who kept the Broad Museum hopping with dozens of imaginative music, film and art events, moved to the Bay Area to join Gass’ team at Stanford.

Gass said the turnover is “normal for a institution, especially one that’s just starting. There was a collaborative spirit that got the thing going, but everybody left because they had great opportunities elsewhere.”

Fulcrum and bridge

Last week, Beal visited the Broad Museum and talked with the staff about community relations. Beal is this year’s Hannah Distinguished Visiting Professor at MSU, a prestigious one-year gig that includes working with the Broad Museum’s staff as a “general adviser” and consultant on a wide range of issues, including programming.

Over his 16-year tenure in Detroit, Beal shepherded the DIA through a major renovation, countless political land mines, a millage rescue and the existential threat of bankruptcy. After turmoil on that scale, the Broad’s staff turnover and identity quest seem manageable by comparison.

“We’ve shown at the DIA that there are ways of making your community feel at home,” Beal said in a phone interview last week. “This is where some critics get a bit nervous, but you have to find out what your community wants from the museum.”

At the DIA, Beal made sure that the explanatory plaques on the walls were translated from academic jargon into everyday language. By comparison, much of the writing on the wall at the Broad has been larded with jargon to the point of impenetrability — even to a few people on the staff (who asked not to be named).

Beal may urge the Broad to undertake a community survey similar to audience research he carried out before the 2007 DIA renovation, which was warmly received by critics and museum visitors.

“Bringing the community and the university together — with art as the fulcrum — is the important thing,” Beal said.

Doherty said she is deeply mindful of the need for community buy-in.

“We have two entrances — one to the university and one to Grand River (Avenue), and that symbolism is important,” Doherty said. “Art and our museum acts as a bridge.”

Breaching the castle

Among Doherty’s jobs before coming to the Broad was directing Lismore Castle Arts, a contemporary art museum in Ireland tucked into a medieval castle. Doherty sees a resonance, across the centuries, with Zaha Hadid’s steel-plated Broad Museum.

“I think of the building as a jewel, but for others it may seem like some sort of impenetrable armor,” Doherty said. “It’s the responsibility of the curatorial team and education team and public programs to provide ways into the armor.”

A fresh slate of public events, including guided walkthroughs and artist talks, student performances, an underground film series and an Acoustic Lunch concert series linked to East Lansing’s popular Pump House Concerts series, will be a key weapon in Doherty’s armor-penetrating arsenal.

This year’s exhibits at the Broad also show a subtle shift in style and emphasis.

In late spring and summer of this year, a visitor could wander through most of the Broad Museum and not see a single human face or form on display. “The Genres: Trevor Paglen,” a high-concept critique of the modern surveillance state, parked ersatz satellites on the museum’s second floor. “East Lansing 2030: Collegeville Reenvisioned” filled the first floor’s main gallery with futuristic, abstracted models and designs of East Lansing’s possibilities.

By contrast, the Broad’s current display of art from the United Arab Emirates is a colorful bouquet straight from the pages of a hip, multimedia iteration of National Geographic, lining the walls with textures, patterns and faces of unabashed beauty. Upcoming exhibits at the Broad, including a major exhibit tracing the history of video art, promise to be anything but sterile.

To Gass, one of the most successful exhibits at the Broad was summer 2013’s “Patterns,” a combination of novel, abstract forms and materials with hypnotic, jewel-like razzle-dazzle.

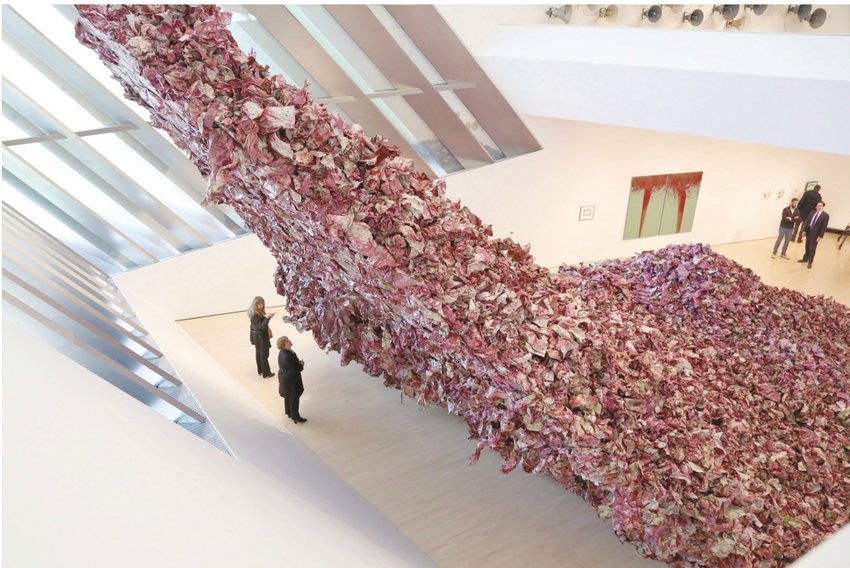

Doherty singled out the massive crumpled-paper installation by Pakistani artist Imran Qureshi, inspired by the shape of the building, as a high point in the Broad’s third year. Qureshi’s forays into East Lansing, painting walls and sidewalks, sparked the kind of public dialogue Rush and Gass envisioned. Doherty wants to see more buzz beyond the Broad’s walls.

“I don’t want anyone going out and saying, ‘That was nice, that was OK,’” she said. “If it’s negative, that’s OK, so long as it’s an excited negativity, an inquiring negativity.”

With the right mix of challenge and beauty, Gass said, the Broad can do things other museums don’t do.

“The white box is coming out of fashion,” Gass said, referring to traditional gallery rooms. “The Broad can be a leader in thinking about how to respond to an exciting space.”

Looking for the right person

Another problem bound to dog the Broad Museum’s next director is lingering resentment over the way the university handled the transition from the old Kresge Art Museum to the Broad.

In 2007, a $12 million plan to quadruple the size of the Kresge and its 7,000 pieces — collected and donated over 40 years — was dwarfed by the bombshell announcement that building and banking tycoon and contemporary art collector Eli Broad, an MSU alumnus, would give $26 million (later beefed up to $28 million) to his alma mater for a whole new museum. It’s still the largest gift in the university’s history.

The catch — or the great leap forward, depending on how you look at it — was that Broad, one of the world’s top art collectors, wanted the new museum devoted to his own passion: contemporary art.

The former Kresge art, now dubbed the “historic collection,” is available for study by faculty and students. The art is also used at the Broad to add a historic depth to themes or ideas expressed in the contemporary exhibits. In the recent Trevor Paglen exhibit, 19th- and 20th-century landscapes from the Kresge collection were juxtaposed with Paglen’s chilling photographs of surveillance facilities.

“We engage with (the historic collection) more than people realize — through research and student involvement, and community,” Doherty said.

But MSU never made it clear to the public why Kresge was axed as a standalone entity, needlessly angering a devoted cohort of Kresge supporters and donors. The most likely reason is that the Kresge collection just didn’t fit with MSU’s new world-class ambitions — but it’s hard to get anyone at MSU to say that. Despite his limited, one-year involvement at MSU and exalted status in the museum world, even Beal was hesitant to go there.

“It’s hard to talk about the (Kresge) collection,” Beal said. “It has a few jewels in it and it represents various cultures. I don’t want to cause offense in any corners, but it … it is not really a free-standing resource.”

Beal, a past master in reconciling conflicting voices in Detroit, said the Broad’s new director and curatorial team will do well not to ignore that part of its history.

“You have people who wanted what they had, and it’s been taken away from them,” Beal said. “The onus is on the museum staff to provide programming that’s vital enough, that uses aspects of the collection, as appropriate, to give the visitor the kind of satisfying experiences that assuages those concerns.”

To Gass, the Kresge fallout and mid- Michigan’s overall wariness of contemporary art make the director’s job at the Broad an exciting opportunity — “for the right person.”

The next director, she said, should be working at the highest level in the contemporary art world, but also excited to share it with a broad audience who hasn’t experienced it before.

“You have to have someone who’s committed to teaching, and I don’t mean just in the classroom,” Gass said.

If the search committee goes for a director whose main concern is maintaining the museum’s prestige in the contemporary art world, the Broad will settle deeper into the university as a high-functioning academic asset, point of pride and expensive brochure icon, but little more.

Ever the optimist, Gass said the Broad’s current interregnum won’t last forever.

“There’s going to be a moment that feels like a transition, but the (Broad’s) reputation in the art world is incredibly strong,” Gass said. “Everybody just needs to breathe for a moment and realize that something great is coming.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here