First, the bad news. Lansing tops communities in the state in municipal pension and other retiree benefits obligations, an estimated $600 million in short and long-term debt obligations.

How to solve that debt and maintain — perhaps even enhance — vital city services like roads, police, fire and more, is unknown. Right now, the city spends about 25 percent of its general fund expenditures on this debt service. If nothing is done, Randy Hannan, chief of staff to Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero, said the debt obligations will crowd out other budget priorities.

And that brings the glimmers of good news.

The debt can be paid out over decades. The pension investments are performing well. For the first time in years, the city is financially stable, reporting small budget surpluses for the last two years. That in turn means officials can consider paying down some of the debt.

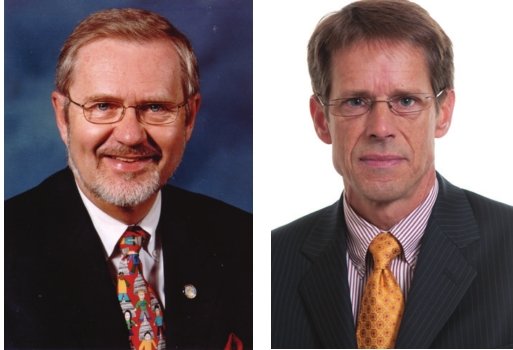

“Is it a crisis?” asked David Hollister, the former mayor whom Mayor Virg Bernero tapped to head the financial health team that advises him. “Eh, who knows.”

Why such ambivalence from the man who is supposed to evaluate and chart the course for fixing the city’s long term financial issues? Because the debt is a moving target — just like the economy. The pension debt is fairly well fixed, Hannan, Hollister and others said; but the health care costs are a variable.

Particularly challenging for those projecting health care costs is the impact of the Affordable Care Act. When the law went into effect, projections were that health care costs, which had been increasing by double digits for decades, would moderate. Last year, Hannan said, that was true. Only one of the city’s two health plans saw an increase, and that was about 1 percent. This year, however, the city is bracing for steeper increases, although what they will be is still unclear.

Complicating the situation is a new accounting rule that requires the pension debt be listed as a liability in year-end financial reports. As a result, it can appear as though the city must pay off the entire $600 million in one sitting, when in fact that debt stretches out over decades.

“Everyone has known this was out there, but when you put it on the balance sheet it looks worse than it actually is,” said Carol Wood, an at-large Council member.

Hollister said that part of the situation with the debt is an accounting sleight of hand but that the debt is still a real one that has to be addressed in the long term.

While there is uncertaintly about the size of the city's debt, there is agreement that it requires action. Wood, along with fellow Councilmembers Jessica Yorko, from the Fourth Ward, and Jody Washington from the First Ward, question the $600 million projection. But all Council members and officials interviewed concurred the debt issue “was real.”

Newly elected Councilmembers Patricia Spitzley, who serves in an at-large role, and Adam Hussain, the Third Ward representative, agreed with the other Council members that there's a problem.

"They told me we were not on the verge of bankruptcy," Hussain said of a briefing he received from Financial Health Team members. He called that meeting 'encouraging."

"But it's real."

Hannan said he “wouldn’t characterize it as a crisis right now. But it could become one if we don’t act.”

But what to do? The city’s taxing authority under state law is near the cap. State revenue sharing, which has been declining for over a decade, is not expected to have a “miraculous” impact, according to Hannan. And while the economy is stabilizing and property values are climbing, state laws interfere with the development of a mirrored recovery in tax capture. That’s artificially stalled by law.

City Council in October authorized the city to spend $100,000 to hire a firm to conduct a study on how cities and states across the country are handling the same debt issues. The state Treasury Department, which has loomed large for several years as the financial boogeyman of emergency manager-dom or bankruptcy, has agreed to pitch in another $100,000 for the study.

“That’s the beauty of the study,” said Council President Judi Brown Clarke, an at-large member. “There is no ‘right’ solution; there’s optimal solutions. We’ll be able to look at those and see what benefits and best serves our fiscal scenario.”

Said Hannan: “The goal of the study is to recommend specific solutions to our legacy cost solutions. The job is to crunch the numbers in those scenarios in Lansing’s specific problems.”

Hollister said the study will look at “what other communities are doing” for possible solutions.

The proposal for the study should be finalized in the coming weeks, and the final product could be available as soon as July, officials said.

Wood said she is interested in seeing whether bonds might be an answer. In that instance, the city would borrow money to cover the legacy costs as projected. That would create a more favorable balance sheet in financial reports, but would also require continued debt service for the life of the bonds. What the interest rate might be is simply unclear.

Oakland County, Hannan noted, has already used bonds to address its legacy cost situation. He also believes the Affordable Care Act may yet come to the rescue in new ways. He noted that retirees may be able to find cheaper healthcare solutions using subsidies and possible a payment from the city through exchanges. That's something he said he expects the study will review and report on.

"It's not like we haven't been aggressive in addressing this," said Hussain. "We've done so much, but we've exhausted our options."

Elected and appointed officials say there is also not one single bullet to solve the problem.

“We didn’t get here overnight, and we’re not going to get out of it overnight either,” Washington said.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here