But emergency manager called the resolution “incomprehensible.” He defended the water as safe.

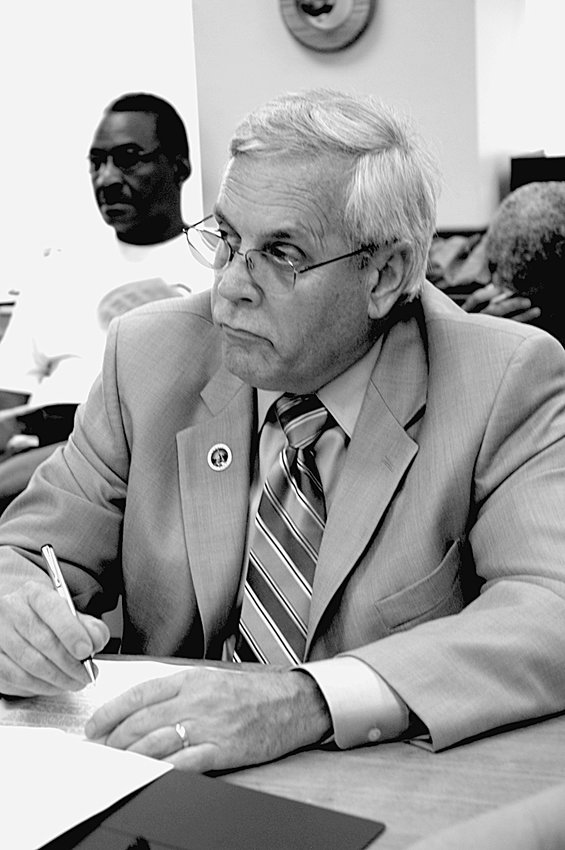

That emergency manager was Jerry Ambrose, well known in Lansing.

Ambrose, 56, who was Flint’s fourth and final emergency manager, had served as Ingham County’s controller for over 20 years before becoming finance director for the city of Lansing and chief of staff for Mayor Virg Bernero. He left in 2011 to serve as chief financial officer for Flint’s three financial managers before Gov. Rick Snyder named him the top dog in January 2015.

The Mason resident — who commuted to Flint during his entire tenure — could be in danger of becoming the national media’s poster boy for governmental insensitivity in the Flint crisis. Twice over the weekend, he was cited in New York Times’ articles as refusing to bow to local demands for better water. “Water in Detroit is no safer than water in Flint,” the Times quoted him as having said.

Indeed, as emergency manager, Ambrose was a leading defender of the Flint River conversion, arguing a switch back to Detroit water would be too costly. A March 3 letter to overseers at the Michigan Treasury Department spelled out his views.

“I am satisfied that the water provided to Flint users today is within all MDEQ and EPA guidelines, as evidenced by the most recent water quality results conducted for MDEQ,” he wrote to Deputy Treasurer Wayne Workman, referring to the state Department of Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

He underlined the word “today” in the letter, written following several boil water advisories made to Flint residents because of e. coli bacteria concerns and after the city had been cited for violations of the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. “We have a continuing commitment to maintain water safety and to improve water quality, and have dedicated resources to assure this commitment will be made.”

Ambrose argued that a switch back to Detroit water would cost Flint residents an additional $12 million a year but doing so was unlikely to address the water issues.

“Changing the source of the city’s water would not necessarily change any of the aesthetics of the water, including odor and discoloration, since those appear to be directly related to the aging pipes and other infrastructure that carry water from the treatment facility to our customers,” Ambrose wrote — a comment eerily prescient. The current emergency stems from the failure to treat the water so that it would not corrode pipes and introduce unsafe levels of lead into what came out of the taps.

Earlier, serving as Flint’s chief financial officer, Ambrose had signed off on the plan to switch from Detroit water to the Flint River in 2013. That switch was completed in April 2014.Ambrose was likely a party to negotiations in 2013 in which Detroit officials offered to lower its rates, according to documents unearthed by the ACLU of Michigan.

Yet on March 5, 2015, Ambrose told a group of citizens in Flint that Detroit officials had told the city to “go get your water some place else.”

“It was Detroit that sent us a letter that said we’re canceling your contract, go find your water some place else,” video provided by the ACLU of Michigan shows Ambrose telling aggravated residents.

The ACLU’s Curt Guyette, a former journalist with an investigative bent, called this statement “a lie.”

Efforts to reach Ambrose for comment were unsuccessful.

How did Ambrose end up making decisions that contributed to the water crisis?

Matt Grossmann, an associate professor of government at Michigan State University, attributed it to the emergency manager law itself.

“As a general criticism of the emergency manager law, the fact is local elected officials are better equipped to respond to the concerns of citizens,” he said. “The emergency manager is laser focused on saving money rather than other concerns that would come forward.”

He said the Flint water crisis was a succession of failures, bureaucratic and legal, and that he was not prepared to assess any blame to one specific person yet.

Ambrose’s role in the crisis is likely to leave him spending a lot of time in the offices of attorneys, as well as federal and state authorities as private lawsuits and governmental investigations unfold.

That’s the reason he gave Bernero on Monday for resigning from the Financial Health Team that advises the mayor on budgetary issues. Bernero had appointed him in 2012 to serve on the panel, which is chaired by former mayor David Hollister.

Randy Hannan, Bernero’s current chief of staff, said in a statement on Monday: “Earlier today, Jerry tendered his resignation from the FHT, indicating that his resignation is not a comment on the Flint water controversy or his role in it, but as a measure taken to not distract from the important work of the FHT.” Over the weekend, four members of the City Council told City Pulse Ambrose should resign from the Financial Health Team. Their views, solicited by City Pulse, prompted Ambrose to quit, Hollister said.

President Judi Brown Clarke, joined by First Ward Councilwoman Jody Washington, Third Ward Councilkman Adam Hussain and At-Large member Carol Wood, said the Flint situation would be a “distraction” to the team’s work if Ambrose remained.

Hussain went further. “My colleagues on Council, other Lansing officials, and most importantly the residents of Lansing, have to be able to trust this group as we move forward in a cooperative manner,” Hussain said. “Unfortunately, that trust has been compromised.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here