Last week, architect Elisabeth Knibbe punched up a few images of Lansing's Eastern High School on her computer.

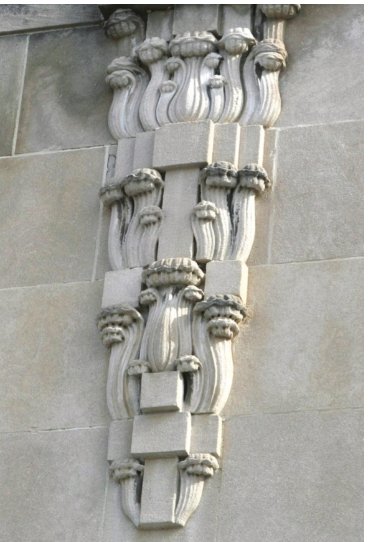

A row of arched windows, embroidered with Indiana limestone, appeared on the screen.

"Oh, wow. It's really beautiful," she said. While historic school buildings are being rehabbed and repurposed for housing and other uses all over the state, the fate of Eastern after its January sale to neighboring Sparrow Hospital is uncertain.

Knibbe works at Quinn Evans, the Ann Arbor firm that has helped restore historic landmarks around the country, from Lansing's Ottawa Street Power Station to Washington, D.C.,'s Old Executive Office Building to Michigan's Capitol. She made her mark in Lansing as the lead architect on the 2014 renovation of the downtown Knapp's Department Store into the Knapp's Centre.

She scrutinized Eastern's meaty brick and creamy masonry, delicately ornamented and topped by copper gutters and a slate roof. "You can't replicate anything like that today," she said.

In January, the Lansing School District sold the three-story, 237,000-square-foot school and 18 acres of its surrounding campus to its next-door neighbor, Sparrow Hospital for $2.475 million.

The sprawling health complex now owns "one of the maybe 25 or so key buildings in Lansing, from an architectural standpoint," according to Robert Christensen, National Register of Historic Places coordinator at the State Historic Preservation Office.

Owner, yes. Proud owner? Hard to say.

In reply to an email inquiry about the future of the building, Sparrow spokesman John Foren did not even mention the building.

Asked whether preserving all or any part of Eastern High School was a priority, Foren replied that Sparrow is committed to "the continued health, education, and economic growth of the area." He declined to comment further.

The purchase agreement is almost as vague.

The school district can lease the building rent free for up to five years while a new school is built. After that, Sparrow has agreed to "honor the historic integrity of the structure," according to a Jan. 21 press release announcing the sale, but the terms give Sparrow a freer hand and say nothing at all about the "structure." It only says that Sparrow "shall develop a plan, which in (Sparrow's) reasonable discretion protects and preserves the historical value of the property."

Even School Board President Peter Spadafore, who approved the agreement with the rest of the board, doesn't know what that means. He said that when it comes to saving Eastern, he is "hoping for the best.”

"Let's keep our fingers crossed," Spadafore said.

Knibbe knows hospitals need a lot of parking.

"That would really, really be a lost opportunity," she said.

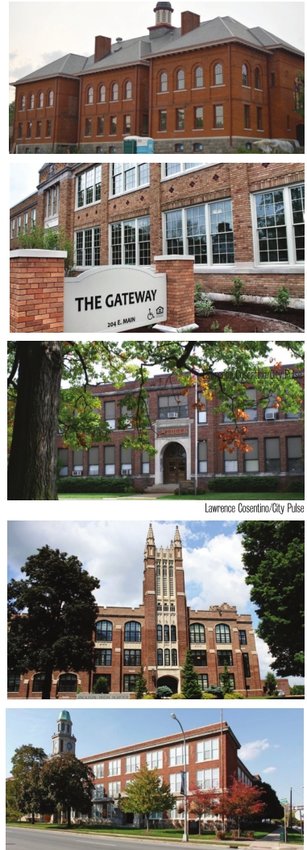

Across the state, old neighborhood schools from the 1920s are being renovated into modern schools or converted into housing, offices and other purposes. Knibbe was the lead architect on two such projects in Michigan, turning Ypsilanti High School, built in 1929, and Fremont High in Newaygo County, built in 1926, into low-income senior housing.

"If anything, (Eastern) is nicer than those," Knibbe said. "This one is a more handsome building."

Christensen said a stream of proposals to rehab historic school buildings have crossed his desk in the past decade.

"It's going on all over the place," he said. "Eastern would certainly lend itself to housing, or a mixture of housing and office space. It's hard to think that rehabbing it would not be feasible."

Raiding the nuggets

James Lynch, president of the Eastern Alumni Association, said his group is "very disappointed" that the school board punted on preserving Eastern.

"People understand they had to sell the school, but people are less than thrilled about the agreement," he said. "It's so vague, nobody knows."

Spadafore tried to put the best face on the deal. He expects Sparrow, "to whatever degree possible, will work to ensure the community has some sort of respect or homage to the history there."

What form might "respect or homage" take? Spadafore said the district would work with Sparrow "to perhaps transfer any meaningful internal architectural features or pieces to a new site."

"There's a lot of great tiling and woodwork and stuff like that, and those could find their way to a new home in (a new) Eastern High School," Spadafore said.

Raiding the shell for historic nuggets, the way you'd pull copper pipes from a demolition site, didn't sit well with Lynch.

"That would definitely be a red flag for me," Lynch said. "If they're just going to tear it down and build an ugly parking ramp there, that's not good."

The heavy tread of Sparrow, one of the region's major employers, has a way of quieting the room. Before the sale, Bob Trezise, CEO of the Lansing Economic Area Partnership, talked as if Eastern would never come down.

“If Eastern High School were suddenly on the market, we would be 100 percent adamant that nothing happen to the school itself,” Trezise said in March 2014. “That is far too significant and beautiful a building to ever tear down. We don’t make those mistakes anymore.”

Last week, Trezise declined to comment on the prospects for the building.

Nancy Finegood, director of the Michigan Historic Preservation Network, called Eastern High a "magnificent building."

“My organization has only sat in front of a bulldozer once, but Eastern might be worth it,” Finegood said. (That was the 1905 Madison-Lenox hotel in downtown Detroit, torn down in May 2005 and turned into a parking lot.)

Finegood's group offered to help the school district get its request for proposals for Eastern to preservation-minded developers, but she said "the (request) was not shared with us."

"My great fear is that they are going to demolish it, and it will become parking, or something new and completely incompatible," Finegood said.

Elusive style

Christensen's memory of Eastern High School goes back to the early 1980s, when Garrison Keillor broadcast an episode of "A Prairie Home Companion" from the auditorium.

"It's hard to say what style to call it," Christensen said. (Knibbe called it "kind of like collegiate Gothic.") "It's sort of arts and crafts but it has allusions to English styles. It's really distinctive and inventive. It goes back to 16th century, 17th century styles — extremely nice."

The school was designed by the Chicago architectural firm of Irving K. and Allen B. Pond, known for rich detail and inventive blending of styles. Pond & Pond, which specialized in academic buildings, designed the student union buildings at MSU, Purdue University and the University of Michigan. (Their father was warden of the state prison at Jackson, Mich.)

To get another expert eye on Eastern's charms, I took a walk around the school Sunday with Lansing preservationist and designer Amanda Harrell-Seyburn, a former contributor to City Pulse's "Eyesore/Eye Candy of the Week."

Like Knibbe and Christensen, Harrell- Seyburn was hard pressed to pin down the school's eclectic style, but that didn't dampen her ardor for the building.

"I'd be OK with Elizabethan Revival," she said. "But it's just good, early 20th century American high school architecture."

Harrell-Seyburn found it "very important" that the details on the facade were meant to be viewed close up, from the sidewalk, not by a driver passing by.

Schools from the 1920s like Eastern aren't just beautiful buildings. They reflect an era in history when schools were a part of the urban streetscape, before they became prison-like, blocky behemoths tucked into vast, mall-sized parking lots.

"This is a neighborhood high school," Harrell-Seyburn said. "People walked here every day. Most high schools today are not neighborhood based. You get there and back by car or bus."

Viewed up close, the squiggly details and window tracery came alive and the limestone blocks looked huge — 3 feet long and 2 feet high.

"We can't afford to build buildings of this quality anymore," Harrell-Seyburn said. "This is full-on masonry, a solid wall, not cheap quarter-inch depth veneer they use now."

We walked from one end of the facade, facing Pennsylvania Avenue, to the other, stopping to look at the stairwells at each end of the school, clad in white stone.

"It's expensive to switch the material, but they're framing the building on either side," she said. "It's very classical, with origins back in the Vatican and other Renaissance buildings."

Every arched and crenelated entrance was, in her words, "a celebration."

"It's the quality of materials, the level of detail," she said. "Those copper gutters will last forever. No one goes out and does a new high school with a slate roof."

{::PAGEBREAK::}

Schoolhouse rock

As state coordinator for the National Register of Historic Places, Christensen goes through a lot of applications. He said there is "no question" Eastern could make the list.

That would make the building eligible for substantial federal credits that would help pay for renovation. Federal historic tax credits pay for up to 20 percent of the total cost of a qualified project, up front or over five years, and they're not the only credits available.

"There's a big interest all around the state in re-using these older school buildings as the school districts abandon them for new buildings," Christensen said. "They tend to be neglected in their later years by school districts that are thinking of moving out, but the building itself is a steel framed, masonry building that is a good building to start with."

Old schools lend themselves well to a variety of uses, but housing is the most frequently chosen option, Christensen said.

"A couple of nominations I have on my desk are for schools around the state, with ideas to rehab them into housing," he said.

Architect Knibbe said classroom buildings "convert very easily" to housing. It so happens that old classrooms are about the same size as modern efficiency apartments.

"The depth between the window and the corridor is good for putting a housing unit in," Knibbe said. "You have these big, wide corridors, gyms and lobbies and libraries, that make great social spaces. High ceilings, big windows, wood floors in some of the classrooms — all these make for very desirable housing."

In May 2015, the first residents moved into the former Fremont High School in Newaygo County, built in 1926. The stately arts-andcrafts edifice, closed in 2012, was converted into a 38-unit low-income and market rate senior housing complex, Gateway Fremont, complete with geothermal heating.

The $11.8 million project used low-income housing credit, federal historic tax credits and a $450,000 Community Development Fund Grant, all of which are still available in Michigan.

In 2005, Ypsilanti High School, a 110,000 -square-foot 1929 building similar to Eastern, was converted into 110 units of senior housing, Cross Street Village. The school was closed in 1972 and falling into extreme disrepair.

Knibbe was lead architect on the Ypsilanti High School and Fremont High School projects.

"They were both financed using the same tools, which are historic tax credits and lowincome housing tax credits," Knibbe said. "They got done without the (discontinued) state tax credits and without extra subsidies from the state. Using the incentives that are out there, you can do these projects and they are economically viable."

Finegood said that any renovation of Eastern would also likely qualify for grants and/or low-interest loans under the Community Revitalization Program, which replaced the state's now-discontinued brownfield and historic tax credits.

Adaptable you

The list of renovated schools in Michigan alone is growing year by year.

In 2013, Flint's 1898 Oak Street School was converted into 24 units of low-income senior housing for about $5 million, using federal grants.

"They did an amazing job," Finegood said. "They have a waiting list."

In 2004, voters in Charlevoix approved a millage to turn its classic 1927 high school into a high-tech library., which opened two years later.

Finegood and Christensen said similar school-to-housing rehabs are finished or under way in Grass Lake, Owosso, South Haven, Detroit and several other Michigan towns. In The Grass Lake project, now called Schoolhouse Square Apartments, the hallways look exactly as they did in the 1920s and 1930s, down to the lockers and drinking fountains, but the apartments are fully modernized.

Old schools are not only being converted to housing, but also to offices and even laboratories. In Lansing alone, several old schools have been snapped up by new-tech companies with specialized needs.

Niowave, a manufacturer of parts for particle accelerators, took over Lansing's 1924 Walnut Street School in 2006. The Neogen Corp., a biotech firm specializing in food safety test kits, bought and renovated two large elementary schools, the 1916 Oak Park Elementary building in 1985 and the Allen Street Elementary in 2005. Neogen CEO James Herbert told the business website NextCity the school buildings cost about a quarter of what a new building would have cost. Even Lansing's creaky 1918 Cedar Street School, a crumbling eyesore since it was closed in the 1980s, was converted into the LEED-certified Medical Arts Building in 2008.

With a potential for housing, office and even laboratory space, Eastern presents a menu of options for Sparrow.

Among the possible uses are temporary housing for families of patients who are in long-term care, or new staff or interns who haven't found an apartment yet.

"Training, continuing education — there are a lot of uses," Knibbe said.

Knibbe said she'd love to get a call from Sparrow and start a feasibility study.

“The Knapp's building — nobody thought we could do anything with that, either, and that's exactly how that went," Knibbe said. "The state hired us to do a study, and it sat there for a while, but eventually it got implemented. We'd be very interested in helping out with a building like this."

At refurbished Jackson High School, Rod Walz is eager to give Sparrow execs a tour. Walz, project manager for the school's spectacular 2005 renovation, said that if Sparrow sends bulldozers over, they might have to contend with some serious steel and concrete, given the construction methods of the day.

Gothic-towered Jackson High, built in 1926, got a stem-to-stern $30 million renovation, financed by a bond issue voters approved by a 5 to 1 margin.

"If Sparrow decides to tear that down, they'll spend more time — I guarantee it'll go over budget," he said. "Come down and I can show you what you can do and how you can do it," Walz said. "It is absolutely phenomenal."

The cost of renovating Eastern depends on several unknowns, including the condition of the building and the ultimate use.

"(Sparrow) is going to have to do their due diligence to find out what is financially and structurally possible, according to their needs," Spadafore said. "There are wants, there are needs and there are practical things as well."

Is it worth it to rehab a fancy old building? Knibbe said it depends.

"Compared to a cheap stick-built building that's built on a green field site, out in the suburbs, and will last 40 years, it's not cost competitive," she said.

"But Eastern is in a great location, next to a hospital, near downtown and it's a beautiful, historic structure." Nothing new, she said, is likely to be cost competitive with preserving a structure that has so many assets.

Knibbe allowed that some features of older buildings, "if they're not in great condition," make it more expensive to renovate, but that's where the incentives come in.

"The fact that the federal government subsidizes these projects with historic tax credits reflects the policy that, as a culture, we think it makes more economic sense to re-use these buildings than to tear them down," she said.

Christensen hopes an application for National Register status for Eastern, and a plan for its renovation, crosses his desk soon.

"It's great that there are a couple of years for discussions of other plans, than just (to) see this become another parking lot," he said. "That's a total waste."

The school district's five-year lease on Eastern gives Sparrow time for study and the community time to sound off on the fate of the building, but that isn't necessarily cause for hope, in Finegood's view.

"My fear is, they say 'four to five years,' and you turn around and oh my gosh, the bulldozers are there," Finegood said. "We've seen that happen before."

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here