There are many carefully forged links in the 39-year-old New York artist’s work, but the chain drops straight into a well of mystery. Sendor spoke extensively about his meticulous methods on a visit to the Broad Art Museum Thursday, but he kept mum about the meaning of his work.

“People who look for symbolic meanings fail to grasp the inherent poetry and mystery of the image,” he said, quoting Belgian surrealist René Magritte. “But if one does not reject the mystery … one asks other things.”

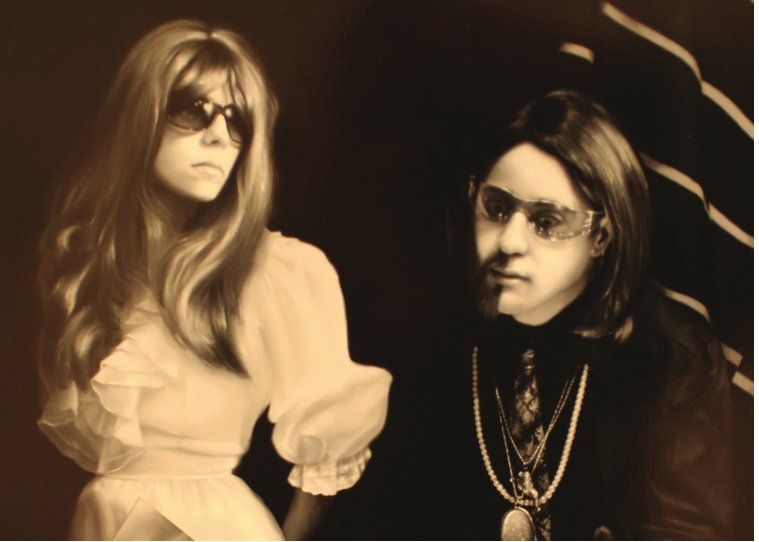

Sendor’s hyper-realistic drawings and paintings will be on view at the Broad through April 24, along with a 13-minute film he directed. To start a project, Sendor rounds up a recurring cast of friends and New York performance artists and directs them in elaborate tableaux that often suggest mysterious rituals.

Then he holes up in his studio, sometimes for months, and paints the tableaux in almost impossibly delicate tones of black, gray and white. He adds surrealist touches like the visual echo of a face in a spray of leaves or a side panel that plays subtle variations on the main image.

The characters have elaborate names and backstories that pop unbidden into Sendor’s head.

When people ask him where his ideas come from — which is constantly — he answers with a quote from the German filmmaker Werner Herzog.

“My ideas are uninvited guests,” Sendor said. “They don’t knock on the door; they climb in through the windows like burglars.”

One of the recurring characters in Sendor’s images, Boris Flumzy, is a sensitive, questing soul with half of a beard. Sendor couldn’t convince anyone in his circle to go around with half a beard for a couple of months, so he played the part himself. (In the film accompanying the exhibit, the close-up, slow-motion beard grooming is so graphic that some young girls couldn’t handle it and walked away.)

Sendor called the half-beard experience “exciting and horrifying.” Even in New York, he drew a lot of stares walking down the street. The Flumzy look added piquancy to the most mundane, everyday acts, including parent-teacher conferences, opening a bank account and air travel.

“I assure you, TSA workers do not like half beards,” he said.

About half of the works in the Broad exhibit have not been shown publicly before. “It’s the first time anyone’s seen them except myself,” Sendor said.

Several of the works were also on view at “Andrew Sendor: Delicates,” a 2015 exhibit at New York’s Sperone Westwater Gallery. Sendor looked around and noted an “amazing difference” between the New York gallery and the Broad.

“There are very few right angles here,” he noted. “It’s a dynamic space.”

The seed for the exhibit was planted in 2014, when Broad Art Museum founding director Michael Rush came to Sendor’s New York studio while writing an essay for the Sperone Westwater exhibit catalogue.

Rush, who died in March, loved art that combined painterly quality and a sense of performance. It’s no surprise that he gravitated to Sendor.

“We talked about my work, art in general and life,” Sendor recalled. “I could tell by the way he was looking at my work that he really believed in the power of art.”

Thursday, Broad Art Museum Curator Caitlín Doherty, who curated the Sendor exhibit, couldn’t get over the contrast between the artist’s mild-mannered persona and the haunting images on the walls.

“He’s so calm,” she said. “He looks like this middle school teacher, and yet all these visions come out of his head.”

Sendor’s talky transparency about his methods and utter opacity when it comes to their interpretation fit together like a ledge and a velvety void.

“This notion of embracing the unknown and embracing artworks that elicit a spirit of inquiry and wonder is always filling the air in my studio,” he said.

In one painting, a character named Fenomeno is seen playing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 35, in the majestic setting of the Geiranger Fjord in Norway, according to the work’s absurdly specific title. All that information, far from providing a helpful backstory, seems to mock the “facts” viewers cling to when they interpret a work of art. The silly specificity pushes the viewer back to the mystery of the image — Sendor’s nefarious plan all along. The painting, he “explained,” captures Fenomeno “at the peak of elation and rapture, just before he melts to the ground.”

The attention to detail in Sendor’s paintings is almost painfully acute, down to the smallest leaf or piece of furniture in the background — only don’t say “background.”

“I regard every single square centimeter as activated space that needs to be addressed with very careful attention,” he said.

Doherty said the most frequent comment she hears about the work is a question: “Is that really a painting?”

Besides breathtaking detail, some of the paintings offer a commentary on detail. One painting contains an image-within-the-image built of 1,435 black, white and gray pixels, each one carefully mapped out by shade. You have to squint to see what’s in the pixelated sections — in one case, two dancers; an LP cover in another.

By popping pixelated images into finegrained, hyper-real settings, Sendor seems to put digital culture in a critical light.

The “often contentious” relationship between painting and photography goes back to the invention of daguerreotypes, Sendor explained. The rise of digital photography has only complicated and accelerated an old rivalry.

For 150 years, he said, “the act of painting has endured sharp, antagonistic reappraisals.”

“Endured” is the key word. People have been telling painters they’re superfluous for a long time. By sheer hard work and imagination, Sendor seems to be defending the archaic art against the latest digital-age “reappraisal.”

He found, to his surprise, that the pixelated parts of his paintings become recognizable not only when you squint, but also when you look at them through a cell phone camera.

It’s a fitting outcome for our times, he said, because “that’s kind of how we experience things now.”

He said it with a wistful shrug, like a man who spends months rendering human faces and tree branches in fine gradations of gray.

“Paintings, Drawings and a Film”

On display through April 24 FREE Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum 547 E. Circle Drive, East Lansing (517) 884-4800, broadmuseum.msu.edu

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here