Dick Peffley, the new general manager of the Lansing Board of Water & Light, was losing sleep.

He was worrying about what would happen to downtown’s power if the aging Eckert plant ever failed.

“It’s a general manager’s nightmare,” said BWL’s spokesman, Steve Serkaian.

The solution is the proposed Central Substation that the BWL wants to build near Reo Town.

But now Peffley has a new worry: Preservationists are outraged that the Central Substation would replace the Tudor-style Scott House and its sunken gardens.

Serkaian was among BWL officials who met with 21 members of the public Tuesday night to explain the project to them.

The 98-year-old Scott House is a largely mothballed city asset of the city, sitting above the Grand River just north of Reo Town. Nestled beside the aluminum-paneled 4,600-square-foot house is a sunken garden, installed by Richard Scott in 1930. The 5.5- acre property was declared dedicated parkland in 2003 by the Lansing City Council.

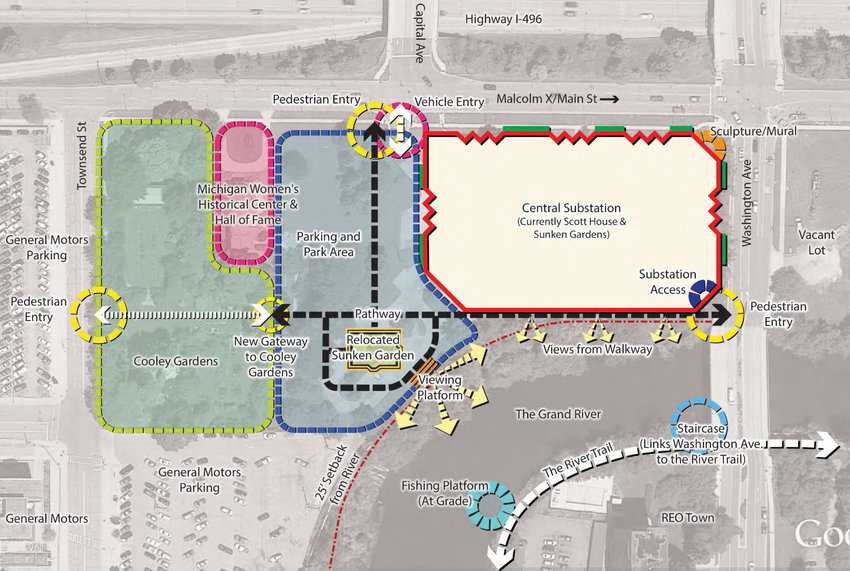

The BWL wants to replace it with the $26 million power substation. It says it would either move or raze the house and recreate the sunken garden behind the formal Cooley Gardens area next door.

The substation’s 50-foot-high steel skeletal towers and small building would be partly hidden behind 20-foot-high walls, decorated with gears and murals of famous Lansing residents such as Malcolm X. The plan would create a walkway overlooking the river. The public utility wants to begin con struction right after Labor Day. Completion will take at least two years.

The location is necessary because it would serve downtown and use existing circuits from the soon-to-be decommissioned Eckert Power Plant.

Development of the old Deluxe Inn site across the street as well as the BWL project “will create a compelling new gateway to REO Town,” said Randy Hannan, chief of staff to Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero.

But preservationists oppose the project.

“It’s a line in the sand,” said Dale Schrader of Preservation Lansing. He’s a landlord in the city who has purchased and restored several historic properties on the edge of Old Town and in the adjacent Walnut neighborhood. “We’re done with the teardowns in the name of urban renewal,” said Schrader, a leading opponent of Niowave’s infamous pole barn.

Activists and some on the Council, citing the City Charter, say the property transfer should be subject to a referendum because it’s parkland.

Hannan said by email, though, that “it is premature to conclude that a ballot question will be required because it is unlikely that the property will be sold to the BWL.”

“BWL is an agency of the City of Lansing, so it is not a foregone conclusion that the city needs to sell land to one of its own agencies in order for them to use it for this purpose.”

Emily Horvath, a professor at the Western Michigan University Cooley Law School, said her review of the City Charter supports Hannan’s contention.

“Section 8-403.6 of the City Charter states that any sale of a park requires approval by the voters,” Horvath said. “It appears that in this case, there will not be a sale, but a reclassification of the property.”

Schrader said a citizen initiative to stop the plan is on the table as a possible option.

He and other members of his group will meet Friday with BWL officials, Serkaian said.

Schrader and Joe Vitale, another developer and head of the preservation group, said this proposal is just another example of the lack of a strong preservation ethic in Lansing. They point to the the Lansing School District’s decision to sell Eastern High School to Sparrow Health Systems with no language to protect the historic building.

Both men, and others in the group challenge claims that restoration of the Tudor home, built in 1918, would cost $1.5 million to $2 million.

“That’s $250 a square foot for renovations,” Vitale said. “It’s easy to throw the numbers out to make it sound impossible. But it would cost maybe 10 or 20 percent of that amount — maybe.”

Both men have restored historic buildings themselves and said they might have an interest in purchasing and renovating the house.

The Preservation Lansing leaders’ cost assessments to renovate the property are based only on exterior inspections of the property. City officials claimed in 2007, in interviews with City Pulse, that the home required significant work on plumbing and electrical systems. The city shuttered the facility as a cost-saving measure in 2008. Since then it has served as a storage facility.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here