Adopting a new, and possibly unconstitutional, policy that shields its law enforcement actions from public scrutiny, Lansing’s City Attorney’s Office is no longer releasing the names of people the Lansing Police arrest and jail.

Adopting a new, and possibly unconstitutional, policy that shields its law enforcement actions from public scrutiny, Lansing’s City Attorney’s Office is no longer releasing the names of people the Lansing Police arrest and jail. Until recently, Lansing, like other area governments, named those it arrested after they were arraigned in District Court. But last week, in responding to a request from City Pulse for arrest records for prostitution, the City Attorney’s Office disclosed it has adopted a policy of protecting the privacy of arrested individuals by not releasing their names.

In an interview Monday, interim City Attorney Joseph Abood confirmed that his office will no longer routinely provide the names of arrestees.

He said the decision is "consistent" with the Michigan Freedom of Information Act. But he also said his office is doing further research to "make sure we're on solid ground."

Added Abood, " "I've always been troubled, as back when I was in private practice, with the release of the names of my clients."

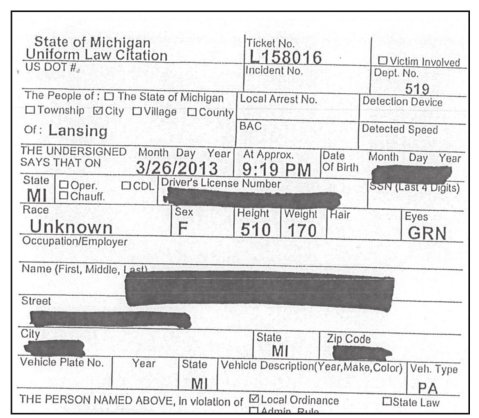

The change in practice was discovered when City Pulse requested information about prostitution arrests in the city.

The response redacted, or blacked out, the names of alleged prostitutes and their customers. Assistant City Attorney Mark Dotson, who handles FOIA requests for the office, justified the response, saying in a letter to City Pulse that to disclose their names “would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of the individual’s privacy.”

In a statement Tuesday, the Bernero administration said there's been "no change in city policy," which requires such decisions to be made on a "case by case basis" by the city attorney.

But the administration said it disagrees with the decision to “redact the names of individuals in prostitution-related cases," the statement issued by Chief of Staff Randy Hannan said.

The administration believes “the public interest in disclosure outweighs the individual’s right to privacy," the statement said. It added that Mayor Virg Bernero has directed Abood "to review the records in question and to provide" an explanation.

Abood defended the move, saying, “We’re following the [Freedom of Information] act. That’s our position.”

The decision to withhold from public scrutiny details of its policing actions raised constitutional concerns for Michael Nichols, a local defense attorney.

“Let’s say I have a client — Jack Smith — and his wife calls me and says, ‘Jack has been missing all night, I think he might have been arrested,’” Nichols said by phone Monday afternoon. “How am I supposed to pursue my client’s habeas rights if the jail won’t tell me their holding him?”

He said the policy violates the Michigan Freedom of Information Act. “It completely frustrates the reason for the sunshine act,” he said.

Lansing policy conflicts with Michigan law and legal precedent, said Robin Luce- Hermann, an attorney with the Michigan Press Association, said by email.

“Michigan courts have repeatedly recognized that ‘In all but a limited number of circumstances, the public’s interest in governmental accountability prevails over an individual’s, or a group of individuals’, expectation of privacy.” Luce-Hermann wrote, citing the Michigan Court of Appeals 2015 decision in Bitteman v. Oakley.

She continued: “Moreover, even if such circumstances apply, Michigan courts have repeatedly recognized that ‘in all but a limited number of circumstances, the public’s interest in governmental accountability prevails over an individual’s, or a group of individuals’, expectation of privacy.’”

The new policy surfaced when the city released hundreds of pages of heavily redacted police incident reports related to prostitution enforcement as well as the register of actions from 54-A District Court related to at least some of these charges. The release also included hours of blurred-out dashboard cam video showing the arrests of persons on prostitution-related crimes. In each of those videos, a Lansing Police officer, in full uniform and driving a marked police vehicle, is seen making the arrests connected to undercover operations.

The reports included 38 cases of people accused of prostitution and 14 cases of men charged with soliciting a female undercover officer for sex for money. In eight of those cases, the men’s cars were impounded under state law, according to the records. Of those impounded, five of the eight were reclaimed by the owner for $500 plus towing and storage costs.

Dotson, the city's FOIA coordinator, declined to discuss the new policy on the record, referring City Pulse to Hannan.

But in a letter to City Pulse accompanying the censored documents, Dotson wrote, “The information is personal in nature and disclosure would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of the individual’s privacy. In addition, disclosure of the information would not advance the core purpose of FOIA, which is to contribute significantly to the public understanding of government.”

The act allows nearly all residents of the state, except those incarcerated, to request documents from the government. “It is the public policy of this state that all persons...be entitled to full and complete information regarding the affairs of government and the official acts of those who represent them as public officials and public employees, consistent with this act. The people shall be informed so that they may fully participate in the democratic process.”

Dotson argued in his letter that releasing the unredacted video as well as the alleged statements of both undercover officers and their targets in prostitution sting operations are “confidential” and their release would interfere with police operations.

Luce-Hermann, the media attorney, challenged that assumption.

“First, this is a discretionary exemption (not mandatory) and requires the balancing of interest,” she wrote.

“Second, this exemption requires that the police demonstrate that disclosure would interfere (as opposed to could interfere).

“Third, Federal case law on this subject indicates that the technique not be well known to the public. It is obviously well known that police talk to and interrogate both victims and suspected offenders. It is hard to imagine how what a suspected offender said could reveal an unknown law enforcement technique. The same is true of what the police said to those they interviewed.”

As allowed under the city’s FOIA policy, City Pulse filed a formal appeal with Lansing City Council President Judi Brown Clarke on Thursday evening. Under state law, the head of a jurisdiction’s public body —in Lansing, the City Council — is charged with deciding appeals.

Municipal police agencies and Michigan Courts favor openness and disclosure in criminal matters. Some examples:

— On Monday, City Pulse visited the East Lansing Police Department and asked Heidi Williams, technology and information supervisor, if she would release the names, ages, races, and charges of everyone lodged in the department’s lock-up between May 5 at 12:22 p.m. and May 6 at 12:22 p.m. She said if City Pulse filed a FOIA, the city would “absolutely” release the list. “We’re about transparency here,” she said.

— On April 12, City Pulse stopped into the Eaton County Sheriff’s Department Offices in Charlotte and requested the police report related to the June 16, 2014. arrest of Todd Michael Brenizer. Eaton county officials promptly released the document without redacting Brenizer’s identity, despite his not being convicted of a crime. In a follow up FOIA, City Pulse requested video of Brenizer’s arrest, and the county released that video without redactions.

— In October 2015, the State Supreme Court upheld two lower court rulings ordering Michigan State University to release the names of student athletes accused of crimes. ESPN had sought the names in incident reports to evaluate whether there had been prosecutorial favoritism for athletes of the university. The courts held that releasing the names furthered an understanding of government operations.

— In July 2009, former Lansing City Attorney Brigham Smith came under fire when he released police incident reports from a sex sting operation targeting men who have sex with men. That sting operation occurred in the city’s Fenner Nature Center property.

Smith released the incident reports with the names of the accused and included the HIV status of one of the arrested men. That resulted in Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero asking former Michigan Attorney General Mike Cox whether the release of the HIV status violated Michigan’s stringent HIV confidentiality law. Cox said the decision to release such information is, in fact, optional for police agencies and not guided by the “clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy” exemption in FOIA or by the state’s HIV confidentiality law. City Council adopted an amended FOIA policy prohibiting the release of medical information contained in police reports.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here