In early autumn of 2006, two anonymous visitors asked for a tour of Lansing’s derelict Ottawa Power Station. It was an unusual request.

The city usually had to coax people into venturing inside the once-splendid landmark on the Grand River, by then an intractable and embarrassing symbol of decay.

The visitors were strangers to Bob Trezise, president and CEO of the Lansing Economic Development Corp. and their contact with the city. When Trezise met them at the power plant gates, they didn’t hand him a business card. Instead, they introduced themselves as Homer and Marge Simpson.

Trezise played along, sensing something big.

They circled the grounds, rattled to the top of the building in a service elevator and picked their way through the pigeon droppings, lingering for an hour and a half.

Many times before, Trezise led quixotic tours of the crumbling, 185,000-square-foot monolith, desperately hoping to interest a deep-pocketed developer. He would point out spectacular views of the Grand River 172.2 feet below, say things like “imagine your office right here,” and sigh as his guests smiled politely and ran away.

But this time felt different. “I’ll never forget when Homer said, ‘This could work for us.’’ Trezise recalled. “It was the first time anyone said that.”

Flash forward to spring 2011.

The people of Lansing are stumbling out of their winter dens, rubbing their eyes, and finding that the transformation of the Ottawa Power Station isn’t a dream.

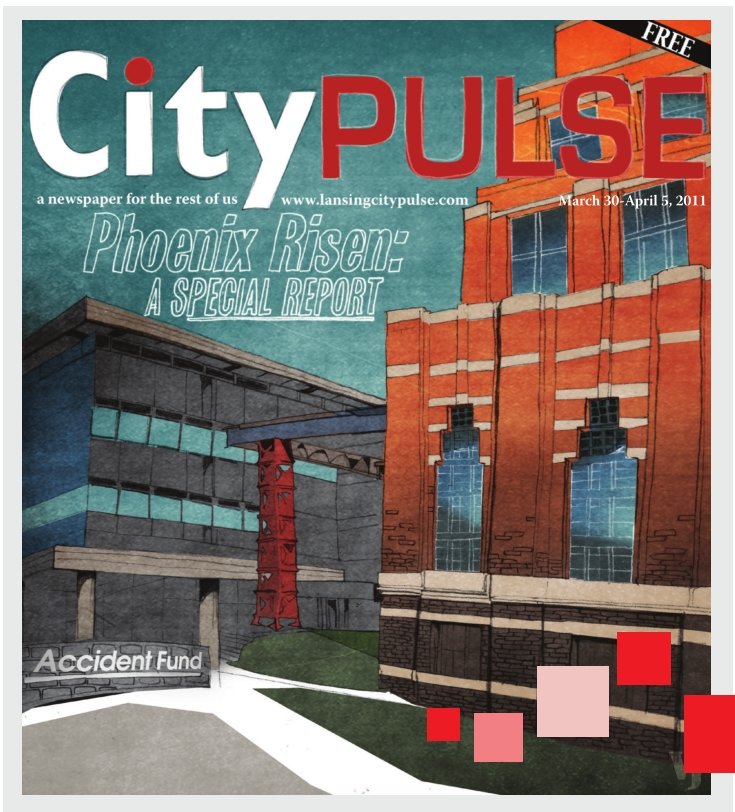

Pinch yourself as hard as you please. It will still be there. The once-rusting hulk, now etched into the postal rolls as 200 N. Grand Ave., really is a sexy, spiffy national landmark, a giant corporate headquarters, and potential anchor of downtown renewal.

The project is more than a high-concept corporate aerie. It’s a national model of private-public partnership and adaptive re-use on a colossal sale, destined to star in hundreds of Power Point lectures at architecture and urban design conferences around the world for decades to come.

The only building in the world that compares to Lansing’s 1939 masterpiece is London’s Tate Modern art gallery, a former power station that can’t hold a candlepower to the Ottawa Station’s dynamic forms and colors. No wonder 1,550 workers spent two and a half years carefully restoring and scooping out the building’s precious shell, tapered like a 170-foot-high flame and colored to match, with masonry that appears to burn from black to orange to yellow as it thrusts upward.

As a result, a 20th-century wonder — a power plant disguised as a downtown office building — has become a genuine office complex and downtown anchor in the 21st.

How could such an un-disaster happen?

The short answer is that a lot of people badly wanted it to happen.

The long answer is longer.

There were so many moving parts to the project that even one of its prime movers, Dan Loepp, president and CEO of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, the Accident Fund’s parent company, called it “highly unlikely.”

“The dominoes fell up,” Loepp said.

Idle since 1992 except for a chilled water plant in the basement, the power station shrugged off several attempts to fill it, ranging from technology center to entertainment complex.

All of them fell short for lack of a big enough anchor tenant.

The station’s Art Deco charms faded, year by year, until it began to stink like a beached whale.

“This was the tough nut to crack,” Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero said. “That was the symbol, either of stagnation or success, and we knew it.”

In summer 2006, six months after Bernero became mayor, Trezise urged him to solicit bids from potential developers across the country. In the development world, a “request for proposal” is like the courtship dance of a bird of paradise. Bernero dreaded public rejection.

“What if nobody wants it?” he asked Trezise.

“Then we’ll know,” Trezise responded. “And we won’t waste any more time on it.”

As the mayor feared, out of 1,600 developers, none came back with financing or a major tenant. There were no bites, but two nibbles — brief letters of interest, one of them from Lansing developer Chuck Abraham.

Abraham didn’t have financing or a tenant, but he had a friend in a high place, Blue Cross´ Loepp. Loepp knew Lansing well. He came to Lansing in 1984 to work for the state of Michigan. Abraham was an old family friend.

By 2006, the Accident Fund, the nation’s 15th largest workers’ compensation company, was growing fast and contemplated a doubled staff of about 1,200 employees by 2021. It was quickly blowing out the seams of its old headquarters on Capitol Avenue in downtown Lansing.

The company was considering a move out of the city, or out of the state, to accommodate its growing workforce. Bernero recalled a retention meeting with noncommittal Accident Fund execs early in his term as mayor.

“I came out of the meeting pretty depressed,” Bernero said.

Once Loepp had the power station on his radar screen, things began to change.

Loepp credits Abraham with buttonholing him about the building. “I probably blew him off two or three times,” Loepp said. “It was just sitting there, pretty much an eyesore, but it intrigued me intellectually because of what we had done in Grand Rapids.”

In 2004, the Blues moved their West Michigan operations from the suburbs of Grand Rapids to downtown into the historic eight-story Steketee’s department store building, part of which dates back to the 1860s. The development helped reanimate a moribund section of downtown Grand Rapids, drawing coffee shops, Schuler Books and other businesses.

Loepp asked Jim Cash, vice president for marketing of the Christman Co., a Lansing-based developer working with the Accident Fund, if he had looked at the Ottawa plant.

Christman was looking around the country for a place to put the Accident Fund but hadn’t seriously considered the site, only a five-minute stroll from the Christman building on Capitol Avenue.

“Like everybody else in Lansing, we were a little jaded about the building,” he said. “So many efforts had preceded us.”

But Christman Co. had prestigious restoration projects to its credit, including the 1990s restoration of Lansing’s Capitol building, the Virginia Capitol in Richmond and Christman’s own corporate headquarters in downtown Lansing.

To tighten the feeling that a great circle was closing, Christman’s construction division laid the foundation for the Ottawa Power Station in 1937.

The dominoes started falling up. Trezise alerted Abraham to the layers of federal and state credits available for the site, including a $26 million Michigan Economic Growth Authority, or MEGA, grant. Offsetting the building’s many burdens were city, state and federal historic credits and brownfield credits.

Abraham admitted he was more intrigued by the stack of credits than he was by the faded glories of the building. Leopp thought of both when he and Abraham looked at the building together.

Enter the Simpsons. Over Thanksgiving weekend of 2006, a month after the anonymous Ottawa visit, Loepp called Bernero at home and told him that Homer and Marge were Blue Cross facility managers from Detroit.

“That was us,” Loepp told Bernero. “Better sharpen your pencil.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here