In 1977, the world for the LGBT community was a different place. No presidents spoke of equality. A measure to ensure equal treatment under the law had been introduced in the U.S. House but died. East Lansing was one of a handful of local governments that barred discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. A guy named Harvey Milk had just become the first openly gay man in office in American history when he was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

In fact, gay liberation was less than a decade old. Only eight years before, drag queens and patrons of the Stonewall Inn in New York ushered in a militant brand of political activism when they rioted to protest police harassment at gay bars. Marching in a pride parade and talking openly about being gay was an act of resistance. People often were fired from jobs, evicted.

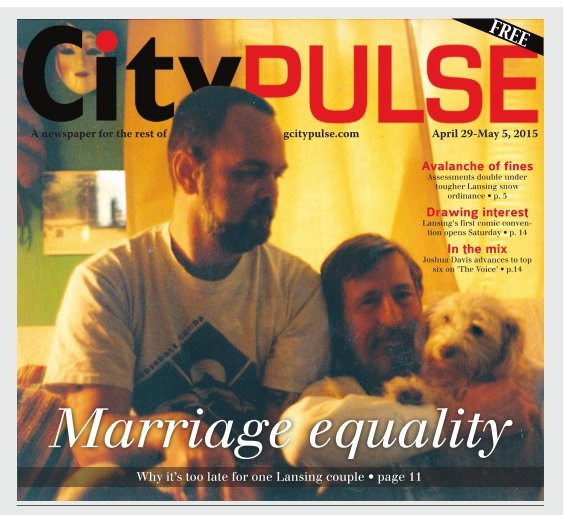

Against this backdrop, a 27-year-old Mykul Johnson of Lansing met Henry David Thomas, 33. Everyone knew him as D.

D, a dancer who choreographed many local productions, was friendly and outgoing, Johnson recalled. The attraction was immediate.

“When I first came over, it was like late in the afternoon,” Johnson said. “He said, at some point early on, ‘I think you’re going to be spending the night.’ I had no objection whatsoever to that. So I did, and I’ve been here ever since.”

The two lived together in a two-story home on the east side. It’s filled with an eclectic mix of masks and pottery, artwork and photo mementos. For 37 years, it was Mykul and D’s home.

On March 21, one year to the day after a federal district court judge in Detroit struck down Michigan’s constitutional marriage ban, D Thomas passed away at age 69. He died of congestive heart failure and COPD. The couple could not tie the knot on March 22, 2014, when a federal court ruling created a short window during which same-sex marriage was legal in Michigan. D was tethered to an oxygen machine in the couple’s living room.

Johnson’s life now consists of phone calls, emails and errands for a local attorney handling D’s estate. By law, he is a legal stranger to D and his belongings. Those all belong to the estate, which is being liquidated.

And despite having spent money to have legal documents drawn up to assure that Johnson would have title to the couple’s home in the event of D’s death, he’s fighting for that too. The Ingham County Register of Deeds Office rejected a quitclaim deed because of legal errors on it.

The result? Five weeks after his partner’s death, Johnson, 63, has no idea, whether he will be able to keep their home.

“Mykul and D´s story is the perfect example of why we cannot delay justice any longer,” said Gina Calcagno, public education campaign director for Michigan for Marriage. “They pledged their lives to one another, they took on all of the responsibilities of marriage and never received the rights they deserved. Couples across Michigan and across the country, like Mykul and D, deserve to have the lives they have built together recognized.”

That’s an important part of what is at stake at the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard arguments Tuesday by defendants from four states, including Michigan. Too late for Mykul Johnson.

Marriage opens the doorway to over 1,000 tangible benefits, from Social Security survivor payments to inheritance protections. It is much more than a promise made in a church, it’s a secular contract recognized by law and creating a unique partnership under law.

“If the couple had been able to legally wed, if D had died, as his surviving spouse, Mykul would have inherited the home (absent any directive in D’s will leaving title to the home to someone else),” said Jay Kaplan of the ACLU of Michigan LGBT Project. “And if D had died without leaving a will, Mykul as his legal spouse also would have inherited the marital home. That is one of the many important legal benefits of civil marriage.”

Michigan is one of 14 states where same-sex marriage remains illegal. It ended up as part of the case before the Supreme Court after U.S. District Judge Bernard Friedman declared unconstitutional the 2004 ban on same-sex marriage and civil unions approved by Michigan voters. The U.S. Appeals Court in Cincinnati reversed his ruling.

A decision in the cases will be handed down by the high court by the end of June, when the court’s annual session ends.

Michigan’s Marriage Amendment was approved by voters in 2004, 59 percent to 41 percent. Ingham County was one of only two counties to reject the measure. But times have changed. Polling shows that the majority of Michiganders support marriage equality now, Calcagno said. And national polls show that six in 10 Americans support the right to marry.

A Gallup poll released last week found that nearly 2 million Americans are in same-sex partnerships, 780,000 of those a marriage.

… The fight for full LGBT equality doesn’t end when and if the Supreme Court rules that marriage is a constitutional right. For instance, in Michigan, unless a person lives in one of 38 municipalities that has a local ordinance prohibiting discrimination, a person can still be fired for being gay or perceived to be. They can also be denied housing. State lawmakers are also working on the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which would allow business owners to refuse to provide services based on “sincerely held religious beliefs.” The state Senate is posed to pass a three-bill package, already approved by the House, that would allow adoption agencies to provide services based on “sincerely held religious beliefs” as well — code for banning same-sex couples from adopting.

For Mykul Johnson, the chance for nuptials is past, something not lost on leading marriage equality voices.

“Because Mykul and D, are both men, they were denied the right to marry and, since D has passed, they never will,” said Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum, who performed Michigan’s first same-sex marriage on March 22 last year, before the Appeals Court blocked Friedman’s order. She was prepared, if the Supreme Court had ruled sooner, or the Appeals court had ruled differently, to wed Johnson and Thomas at their home.

“This is a horrifying reality many same-sex couples have faced and continue to face. That is why this ruling is so important. — to allow all people, to allow all love, to be treated equally."

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here