Michigan State University’s Broad Art Museum is planning to lease a space across Grand River Avenue where it will showcase art from the former Kresge Art Museum, the Broad’s new director, Marc-Olivier Wahler, said in an interview with City Pulse Nov. 17.

Wahler called the former Kresge collection “a pillar of the museum.” He hopes to secure the space in 2017 “if all goes well.” He didn’t say how large the space would be and offered no more specific details, but he described the project as “very real.”

“We want to open across the street with a new space where we can show this important collection,” Wahler said.

The proposed new space not only has the potential to park historic works of art among the burger joints and comic book stores of Grand River Avenue’s commercial strip, it would further one of Wahler’s top priorities as he begins to make his mark on the Broad: extending the museum’s reach into the surrounding community. (For more of Wahler’s plans for the Broad, see related story, click here.)

It might also heal a lingering sore spot left by the Broad’s handling of the Kresge collection.

“We could attract again people who have been bitter about having donated work to the Kresge and then learning their donation is going into storage,” Wahler said.

The new space may contain some contemporary art but would be “90 percent” art from the former Kresge collection, Wahler said.

“We want to engage all these people who were active with the Kresge,” he said. “It’s a very concrete plan. It’s just a question of raising money.”

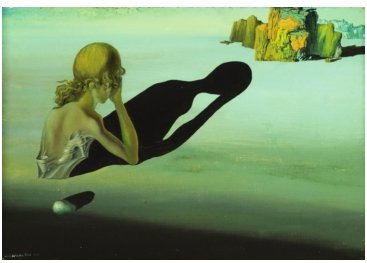

The Kresge Art Museum closed its doors in July 2011, just before the Broad Art Museum, devoted to the contemporary art favored by major donor Eli Broad, opened in November 2012. By that time, the Kresge had amassed about 7,500 works of art, from Greek and Roman artifacts to Islamic manuscripts to European portraits and landscapes, as well as works by 20th century artists such as Alexander Calder and Salvador Dali.

Wahler said the former Kresge collection is part of what makes the Broad Museum a genuine museum, as opposed to an art center with rotating exhibits.

“An art center is more on the horizontal dynamic, but a museum is more on the vertical — it has roots,” Wahler said. “It’s very important to give this verticality of thoughts. We have a fantastic collection.”

Ironically, the Broad Museum juggernaut would never have rolled over the Kresge in the first place if it hadn’t been for the Kresge’s passionate friends network.

Plans for a new art museum at MSU go back to 1987, but Kresge supporters’ goal, well into the construction phase of the Broad Museum, was to get more room to display the cramped Kresge collection, not less.

In 2003, a fundraising group, Better Art Museum, and the Friends of Kresge unveiled plans to quadruple the Kresge’s space and renovate the building.

“The quality of the collection has always far outclassed the facility that housed it,” former Kresge Art Museum director Susan Bandes said in 2003.

Besides the more well-known names, Kresge was home to exotic gems such as a 12th century Chinese tiger pillow (the finest in the West, according to the museum plaque), an ancient Roman mosaic floor, a sculpture by Auguste Rodin, a box by Joseph Cornell, a 17th century oil portrait of St. Anthony of Padua and many works from the mid-20th century.

“If the exhibit can be faulted, it’s for an extra-artistic reason — the inadequacy of the exhibition galleries,” art critic Roger Green said in 2003. “The burgeoning art collection deserves a proper home.”

To its ultimate regret, the Better Art Museum group asked billionaire MSU alumnus Eli Broad for help with the expansion and took him on a personal tour of the Kresge in 2004. Unimpressed by the building, the collection and its obscure location in the middle of campus, Broad said he wasn’t interested in expanding the Kresge. Instead, he offered a more “transformative” gift: $26 million, later beefed up to $28 million, the largest gift in the university’s history, for a whole new museum, designed by one of the world’s top architects.

But Broad wanted the new museum to be devoted to his own passion, contemporary art.

At first, Kresge donors and support groups welcomed the advent of the Broad. Better Art Museum even continued its long series of fundraisers and gave the money to the Broad Art Museum fund, hoping the new museum would accommodate Kresge’s art.

In a 2007 statement, Bandes said she was delighted with the Broad gift, and predicted the new museum would be “a fitting home for the display, interaction with and contemplation of works of art in the university’s collection and in special exhibitions.”

The last Friends of Kresge booklet, published in 2010, clung to the same hope: “The arts community and art museum friends look forward to realizing their long held ambitions for exhibitions and display space.”

A source close to the Kresge, who asked not to be named, said that early designs for the Broad Art Museum included gallery space set aside for the Kresge collection, but the space disappeared in later drafts.

After the Broad opened, university officials kept insisting that the Kresge collection had not been deep-sixed but merely become a part of the Broad Art Museum.

Selected Kresge items did see sunlight at the Broad, as when landscapes from the Kresge collection were juxtaposed with artist Trevor Paglen’s exhibit critiquing the modern surveillance state. But the connections between old and new often came off as strained at best and a sop to Kresge supporters at worst. Bringing isolated artworks upstairs to “contextualize” Broad exhibits was not what Kresge’s donors and friends had in mind.

University officials, including Linda Stanford, Associate Provost for Academic Services, never made it clear why the Kresge had to die in order for the Broad to live. But the Broad’s first director, Michael Rush, came close to identifying Eli Broad’s fingerprints in a 2012 interview with City Pulse.

“When you have philanthropists entering the situation at that level of giving, which is extraordinary, and it is the donor intent for the museum to be a contemporary one, then that is what we embrace,” Rush said.

Rush died in 2015. Wahler, his successor, surveyed the Broad’s assets after arriving in East Lansing in July 2016 and decided it was time to take better advantage of a neglected asset.

“It’s a university museum,” Wahler said. “This collection is made for students, for research and for the community. For me, this is crucial. It’s not only an arts center where we do activities. This collection is a pillar of the museum.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here