“On the first day of class, I saw this little old lady coming down the hall, and I said to myself — or was it God? — ‘please don’t let that be her.’”

The more they dread Stark, the better she likes it. At 86, she is Exhibit A in her own long-running class on dealing with workplace diversity.

“They come in thinking I’m going to be an old fuddy-duddy,” Stark said.

Flipping prejudice into respect is her stock in trade. About 10,000 students have taken Stark’s Lansing Community College’s class in diversity in the workplace during her time there. (Other instructors have also taught alongside her.)

Last week, she led her last class at LCC. She is retiring this year after 40 years of teaching.

Martha Bibbs, the first African-American and first female director of personnel service for the state of Michigan, has known and worked with Stark for most of those years.

“She has been consistent in her dedication to issues of diversity,” Bibbs said. “She’s lived it, and she teaches it.”

That dedication even extends to Stark’s TV habits.

“I never watch ‘Mad Men,’ because I don’t want to go back to those days,” she said.

Moved to tears

The first time Cindy Jackson sat in on one of Joanna Stark’s classes, she was moved to tears.

“A lot of people were,” Jackson said. “Her class opened me up on a much deeper level.”

The heart of Stark’s approach is to bring guest panelists to her class to talk about their lives as women, African- Americans, people with disabilities, Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, LGBTQ people or members of any group that is marginalized or stereotyped.

Jackson’s husband is J.J. Jackson, a former MSU faculty member and advocate for people with disabilities. He has appeared on Stark’s panels for 20 years, both as a blind person and as an African-American man.

Cindy Jackson often joined her husband on Stark’s panels to talk frankly about love, logistics and married life when one spouse is blind and the other is not. She once told Stark’s students about her first encounter with J.J. Jackson, when she was in her stressful third week as a driver for Spec-Tran, CATA’s extended service for people with disabilities.

“I was very overwhelmed and had a van full of people, and I asked how to get to Grand River,” she said. “The only guy who answered was this blind guy in the back of the van.”

She eventually fell in love with “the blind guy” and married him.

The stories told in Stark’s classes resonate beyond the categories in the syllabus. One of Stark’s students approached Cindy Jackson after the class and told her that although she had no disability, their story had opened her up to the possibility that she, too, could be happy in love and life.

“That just blew me away,” Jackson said.

Stark’s disability panels include people with hearing impairments, cerebral palsy and, perhaps most revealingly, people with “hidden disabilities.”

Among the latter is another LCC teacher, Sylvia Wood, who, at 17, was one of the first people in Michigan to get a pacemaker. Wood looked able-bodied at a casual glance, but her story turned a light on for Cindy Jackson.

“Sylvia talked about fainting, passing out, being weak and not being able to do things,” Jackson said. “People told her she was just trying to get attention. It made me think deeply about what people with disabilities go through.”

In Stark’s class, J.J. Jackson has fielded all kinds of questions about dating, how he handles his home, how he matches up his clothing, what it’s like to be a father as a blind person. He tells them about his high-level job as a human resource manager at Amoco Oil in Chicago and explains how he manages interviewing job applicants, arranges travel and handles other work demands.

“They’re afraid of the unknown, of our disability, and it’s up to us to eliminate those barriers of fear and remind them that we’re just like they are,” Jackson said. “We have the same hopes, the same desires and pains. We’re all connected in this big universe.”

Martha Bibbs said some students come into the class “very skeptical,” and Stark doesn’t discourage them from saying so. Bibbs served on Stark’s panels several times with her husband, former MSU track and field coach Jim Bibbs. She didn’t mind when a white student asked her why African-Americans “stick together” in cities and don’t move to the country. Far from being offended, she welcomed the chance for dialogue in the safe space Stark had created.

“We answer them honestly,” Bibbs said. “It’s not a situation where they feel they are being blamed. We have just got to get to know each other.”

Bowling Green and beyond

Joanna Stark wasn’t too fond of milking cows, cleaning chicken coops and “slopping hogs” on a farm near Bowling Green, Ohio, where she grew up.

But she excelled at business classes, typing and shorthand at Bowling Green State University, all the while suppressing a deeper desire to become a doctor.

“Girls weren’t encouraged to go in that direction,” she said.

She parlayed her business skills into part-time jobs almost immediately, but what she enjoyed most at BGSU was singing in choir. The experience had an impact on her life that went beyond music.

The choir director took the group to the East Coast and into the South, a new experience for Stark and the other members.

On one tour, just inside the Mississippi state line, the choir bus stopped and the director let everyone off for a daily one-mile walk. Stark and a few other women wandered into a nearby field to prod the spindly, fluffy cotton plants, which they had never seen before. A man on horseback gallantly approached them and asked what they were doing.

They told him they were on their way to Tougaloo College, a historically black college near Jackson, to perform a concert.

He ordered them off his property.

“All this Southern charm, then boom — when he found out we were going to a black college, he kicked us out,” Stark said. “It was a defining moment for me. I had really no idea of discrimination, other than against girls.”

The choir went on to Tougaloo College, sang the concert, stayed in a dorm with black students and had a great time.

About 40 schools around Bowling Green were interested in hiring Stark, but she wanted to go to a big city and opted for Cincinnati. She taught typing in an inner-city neighborhood and had only one white student in her class.

In 1961, Joanna moved to East Lansing with her husband, Stanley Stark. A professor at the University of Illinois at the time, Stanley had just been hired at MSU, where he would teach for 31 years.

As a business management professor at MSU, Stanley Stark introduced courses on women and minorities in the workplace.

“They didn’t even know how to spell ‘diversity’ back then,” Joanna Stark said.

She spent much of their early years together at home, raising three kids, stirring a pot with her left hand and holding a book with her right. She was overjoyed to live in East Lansing’s ethnically diverse Flower Pot Neighbor hood, west of Harrison Road and south of Kalamazoo Street, where she still lives. She gladly sent her kids to the multi-hued Red Cedar Elementary.

As a haven of diversity, the neighborhood fell short in one respect. The Starks were one of only two Jewish families who lived there in the early 1980s. (Stark converted to Judaism, her husband’s faith.)

“I remember a third-grader at Red Cedar saying, ‘Do you live in a tent?’” Stark said. “I thought to myself, ‘They’ve been reading too many Christian Bible stories.’”

Power and pushback

Joanna Stark admitted that her husband, a Jew from the Bronx, was more “sophisticated about differences” than she was at first, but she caught up fast. After many of Stanley Stark’s classes, his panelists and students gathered at the house to eat and socialize.

As her kids grew older, Stark found part-time work at Michigan’s Civil Service Commission and got involved in a variety of causes and activities. For 20 years, she read newspapers for the blind on the radio.

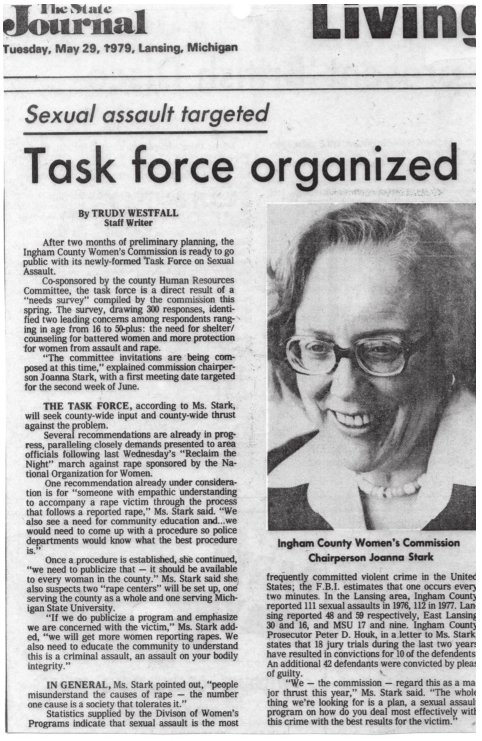

In the 1970s, U.S. Sen. Debbie Stabenow, then the chairwoman of Ingham County Board of Commissioners, appointed Joanna Stark to lead the Ingham County Women’s Commission to investigate employment rights, domestic violence and other issues relating to the status of women in the county. The commission set up shelters and counseling centers in Ingham County and at MSU.

A few male county commissioners pushed back, insisting that domestic violence was not a problem in Ingham County — and they weren’t the only opponents.

“A guy who used to run a gun shop would drive by (the shelter) and check how many lights were on,” Stark recalled.

The Women’s Commission also set up a task force on sexual assault, which was also opposed by some of the male commissioners.

Stark taught management training at nearly every state prison in the 1980s, when women began to be hired as corrections officers.

“They were the toughest,” she said. “They didn’t want to hear about women.”

Male resistance to gender equality never comes as a surprise to Stark.

“Who wants to give up power? Nobody,” she said.

Stark found that the best way to win men over, whether she was dealing with a corrections officer or a county commissioner, was to ask how they’d feel if their own wives or daughters had been unfairly treated.

“Men with daughters are converts,” she said with a trace of irony. “It’s funny. You’d think they would (be) with wives, but there are so many men who feel they can tell (their wives) what to do, how to vote. That happened a lot last November.”

When Stanley Stark retired in 1991, he had little trouble making the case that his wife was qualified to take over his MSU workplace diversity class.

Before long, LCC asked her to teach a variant of her MSU diversity lessons. The syllabus the Starks developed has been adopted by criminal justice and police academies and nursing schools around the state.

‘I won’t be quiet’

In one of Stark’s most enlightening exercises, she announces to her students that she is a magician who can change their sex and asks them how they expect their lives to change the next morning.

“That stymies men,” she said. “They don’t get beyond saying, ‘I wake up in the morning and play with my boobs.’ Seriously, I have gotten that.”

After the election of Donald Trump, Stark is less sanguine than ever about the country’s progress where racism and sexism are concerned.

“I fear right now that our differences have been enhanced by the political situation,” Stark said. “I’m feeling very unsettled about it; I didn’t think we’d end up here.”

On the other hand, she has been heartened by recent progress in rights for LGBTQ people. She recalled a class 10 years ago where a student started to cry after a gay panelist spoke.

“He seems like such a nice man, but he’s going to Hell,” the student sobbed.

“I don’t have that anymore,” Stark said. “I hope it continues, but I don’t know. I still see some hate.”

After decades of pondering human nature — and often fighting it — Stark said she has learned as much as she has taught.

“I do think men and women are wired differently,” she said. “I have finally accepted that men will not stop looking at women. I don’t care if all they do is look. But they don’t give women enough respect in what they can do.”

With her last class at LCC under her belt, Stark hasn’t decided what she’ll do next.

“I won’t be quiet, I know that,” she said. She will be spending more time at home, helping her husband with his mounting health problems. They have been married for 62 years.

She is still troubled by gender disparities in education, a problem she relates to personally. When she was growing up, her mother limited her to one Saturday trip to the library and two books a week, which she usually had read by Sunday. Almost 70 years after leaving the farm, her early thoughts of becoming a doctor still nag at her.

“I might want to work with the push for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education for girls in the schools,” she said.

In the meantime, it’s no small comfort to know she has planted seeds of tolerance in thousands of hearts and minds.

She keeps her glowing student evaluations like rare meteorites. One of them is the cringing student evaluation cited at the beginning of this tale, which goes on a bit further.

“The joke was on me,” wrote the student who dreaded the approach of the “little old lady” on the first day of class. “There is such a wealth of information to be shared that it is a shame 16 weeks are almost over. I will certainly be more open to any teacher or manager that I have after this.”

Stark smiled as she watched me read it. “Stanley put that one up,” she said. “You can’t ask for much more that that.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here