The program is still in the planning stage, but with the change in presidential administrations, the availability of federal funds for the program is uncertain.

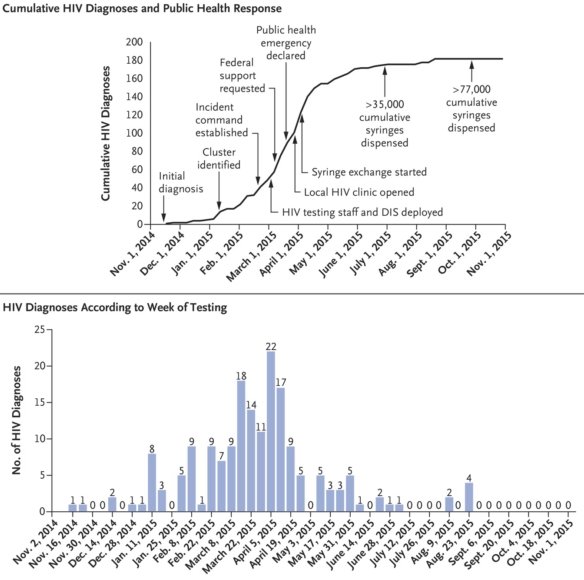

In February and March of 2015, 55 new HIV cases were reported Scott County, Ind., up from about five new cases a year in previous years. When the outbreak happened, Indiana law prohibited needle exchange programs. By the time then-Indiana Gov. Mike Pence handed down an emergency order allowing needle exchanges at the end of March, over 100 people in the small community were infected with HIV. By October of that year, reports of new HIV infections had dropped to less than one per month, according to a study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The rural county seemed like an unlikely place for an HIV outbreak, but the area had also been hit hard by the injected opioid epidemic sweeping the nation. Ingham County officials and health experts say that with the alarming rise of opioid use in Ingham County, they want to head off a Scott County-scale outbreak here.

“We have some of the higher opioid and heroin mortality rates in the state,” Ingham County Health Officer Linda Vail said. “The last thing we want on our hands is some thing like (the Scott County outbreak).”

Ingham County already has the highest HIV rate in Michigan outside of Detroit, according to the state’s Department of Health and Human Services. In 2015, the county had 175 cases of HIV per 100,000 people. Ominously, opioid-related deaths have spiked in Ingham County, from 14 reported in 2003 to 68 in 2015.

An ad hoc committee on needle exchanges reported to the Ingham Community Health Center in fall 2016 that “it is clear (…) that injection drug use is on the increase” in the county.

“We are certainly at increased risk of HIV and hepatitis transmission,” Vail said.

Ingham County Clerk Barb Byrum, a member of the ad hoc needle exchange committee, said “it will only take one person who is in the community that uses and shares needles to have an outbreak” similar to the one in Scott County.

A needle exchange program would help prevent the spread of HIV, reduce the Hepatitis C rate among intravenous drug users and reduce the number of emergency room visits caused by drugs in Ingham County, the report said.

When the risk of an outbreak is this high, conventional treatment programs don’t work fast enough, Vail said.

“If you’ve ever worked with people who are addicted to opioids and heroin, it takes them, on average, five or six times going in and out of recovery until they finally recover,” Vail said. “We need to meet people where they are in the meantime to try to maintain other aspects of their health and protect the community from the risk of transmission.”

Byrum said the needle exchange program is “desperately needed” in Ingham County.

Ingham County Commissioner Todd Tennis, who also served on the ad hoc needle exchange committee, said the program will likely be administered by a private nonprofit, and talks with possible partners are underway.

“Minor” adjustments of local ordinances will be needed to implement the program, according to the ad hoc committee report. Lansing ordinance restricts the use of drug paraphernalia.

“The city would have to take steps to change those ordinances and local rules so people would feel comfortable to get clean needles,” Tennis said.

Vail said the county health department has been in contact with the Lansing City Council’s Committee on Public Safety and the mayor’s office “related to the potential of changes that would get that out of our way, and they’re prepared to review it and see what they can do to help.”

Funding for the program, however, would have to come mainly from the federal government.

“The sticky part is that there’s not a whole lot of budgetary space, either at the county level or local unit levels,” Tennis said.

According to U.S. Center for Disease Control guidelines, federal funds can’t be used to purchase sterile needles or syringes for illegal drug injection, but can be used to support a “comprehensive set of services” including staff time, testing equipment and other supplies.

To get a CDC grant, local health departments must show evidence that their area is either experiencing or at risk for “significant increases in hepatitis infections or an HIV outbreak due to injection drug use.”

Tom Price, the physician and congressman from Georgia picked by President Donald Trump to head the Department of Health and Human Services, voted to stop federal funding for needle exchanges in 2009 and voted in 2007 to stop the District of Columbia from using non-federal funds for needle exchange programs.

However, Price represents a district north of Atlanta where heroin-related deaths have increased dramatically since 2013, according to data released by the Big Cities Health Coalition Project. Price’s wife, Betty, an anesthesiologist who serves in the Georgia state legislature, pushed through the Georgia House in March a bill that would have allowed homeless shelters, drug treatment centers and other social service organizations to distribute sterile syringes to intravenous drug users, but the bill failed in the state Senate.

Supporters of needle exchange programs hope the recent spikes in injection drug use and related outbreaks in HIV and Hepatitis-C in Mike Pence’s and Tom Price’s home states will influence the CDC to protect the programs, even under a Trump administration.

Vail, Byrum and Tennis all cited another significant benefit of a needle exchange program. For many injected drug users, such a program is a first contact with counseling and treatment services and a gateway to recovery.

“As opposed to this population living in the shadows, unable to even find help, hopefully this program can provide a safe space where they can start to reevaluate their choices,” Tennis said.

Tennis said it’s “impossible to know” whether a Scott County-type event is likely to happen here, “but it’s better to take steps to prevent that happening rather than react to it after it happens.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here