Even on a good day, the placid waters of the Great Lakes are beguiling. Beneath these calm waters lie thousands of shipwrecks.

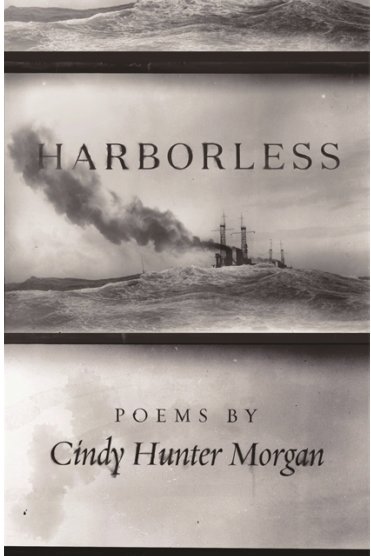

MSU Professor and poet Cindy Hunter Morgan’s latest poetry collection is a transformative look at the shipwrecks that dot the Great Lakes. “Harborless,” which comprises 40 poems, is partly history and partly imaginative reinvention of the lives that were lost in the tragedies.

Anyone who grew up on or near a Great Lake or took a summer vacation up north has likely stumbled upon some remnant from a shipwreck — pieces of wood, clothing and even entire structural beams often wash ashore, especially following a storm. That’s exactly how Hunter Morgan became fascinated with what lays beneath the world’s largest bodies of fresh water. Experts estimate that a minimum of 6,000 shipwrecks have occurred on the lakes, taking upwards of 30,000 lives.

“My grandma grew up in Oceana County and we camped there every summer. Near the Stony Lake channel, where it enters Lake Michigan, I always saw remains of shipwrecks,” Hunter Morgan said. “That, coupled with my great grandfather, who sailed the lakes to earn money so my grandmother could go to Michigan State College in the late 1920s, and I became fascinated with shipwrecks.”

The inspiration for individual poems includes objects from shipwrecks that litter the lakes’ floor.

“There are barrels of whiskey, juke boxes, cars and whole trains lying on the lake floor,” she said. “It’s bizarre what’s on the bottom.”

There are even rumors that a German World War I submarine was scuttled after a victory tour and lies somewhere at the bottom of Lake Michigan.

Hunter Morgan’s poem “Rouse Simmons, 1912” recounts the sinking of what was called the “Christmas Tree Ship,” which sank with 17 men and 5,000 Christmas trees.

“Fishermen wondered why they caught balsam and spruce, their nets full of forests not fish,” she writes.

Hunter Morgan, who grew up mostly in the Lansing area, said she began this collection of thematic poetry in 2013, before it was accepted for publication by Wayne State University Press. She has published two chapbooks, “The Sultan, The Skater, The Bicycle Maker” and “Apple Season,” but “Harborless” is her first book of poetry. Her next project is a collection of poems that will pay tribute to her grandmother.

“She was very important in my life,” she said.

The poems will explore the unusual job held by her grandmother, who took on the role of an “Indian Princess,” a sort of cultural ambassador who travelled Michigan promoting the prevention of tuberculosis. Hunter Morgan is researching the extensive records surrounding tuberculosis in Michigan that are housed at the MSU Archives.

It was recently announced that she has won the Moveen Prize for Poetry, which includes a month-long residency in Ireland at the ancestral cottage of fellow Michigan poet Thomas Lynch. The ocean-side lodging, on the Loop Head Peninsula of West Clare, is funded by the Lynch and Sons Fund for the Arts based in Lynch’s home of Milford, Mich.

This summer, Hunter Morgan plans to visit several Great Lakes port cities to promote her book, including Chicago, Mackinac Island, Petoskey and Marquette.

Another poem in the collection, “Pewabic, 1865,” tells the unusual tale of what was left behind when a ship carrying 150 Union troops sank near Thunder Bay in Lake Huron after colliding with another ship.

“When the ship was found, divers found a card table complete with an unfinished game of cards,” she said. “It was a live action scene. It was the stuff of life, still there and preserved.”

Hunter Morgan said she was also inspired by the people who went to their death on the ships.

“People were sort of an entry point for a lot of poems, and I used a sense of an imagined life of the people who sailed the lakes,” she said.

In the poem “Sidney E. Smith Jr., 1972,” for example, she writes about a ship’s pilot contemplating his guilt following a collision. In “Independence, 1853,” Hunter Morgan writes about the ship’s cargo exploding in fire.

“The crew clung to bales of hay, flotsam once meant to feed the horses in mining camps on the Keweenaw,” she writes.

“I imagined a sailor who, clinging to a bale of hay, represented the juxtaposition between earth and water,” she said.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here