When the doors at the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility closed behind Lora Rex Lempert for the first time, she had no idea what she would encounter. It certainly wasn’t prison as portrayed by Netflix’s “Orange is the New Black.”

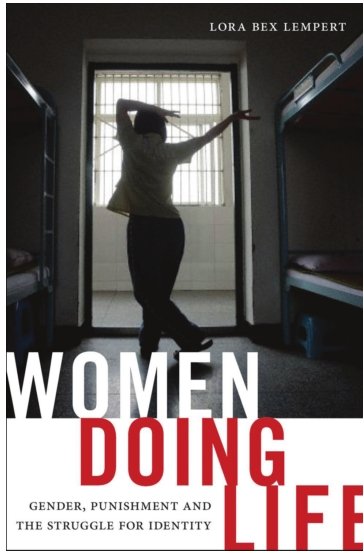

“My ongoing interactions with life-serving women opened a new world to me. A world that I never considered, a world that was not in any life plan for me, a world that I did not know existed.” she writes in her book, “Women Doing Life: Gender, Punishment and the Struggle for Identity.”

Lempert, professor emerita at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, had no idea when she began teaching in 1993 that she would spend a significant portion of her academic career studying 72 women who were sentenced to life in prison with no hope of parole. Most of the study took place from 2010 to 2011, when more than 170 women in the U.S. were serving life sentences.

Lempert, now retired, lives in San Francisco. Her interest in women in prison came out of her work studying violence against women, Lempert said in a visit to Michigan to accept the 2017 Notable Book Award from the Library of Michigan.

“(Violence against women) was the spark to study lifers,” Lempert said. “Of the women in prison, 85 percent were in an abusive relationship.”

She also said many of the lifers are there for crimes committed “behind a man.” For example, a man may have pulled the trigger, but the woman may have set the victim up to be robbed.

“Like most people, I had formed ideas from TV shows about women in prison, but what struck me was how public perception was so wrong,” Lempert said. “Some of the finest women I know I met in prison.”

Lempert conducted two to three focus groups a week and asked the imprisoned women to keep personal diaries. She found an incredible self-determination among the women, despite their knowing they were sentenced to life.

“They are incredibly strategic, have diverse skill levels and create meaningful lives,” she said.

In addition to classifying or identifying certain characteristics of those behind bars, Lempert also details how the women adapt to becoming prisoners and navigating what she calls “the mix.”

A chapter titled “Eating the Life Sentence Elephant” delves into how same-sex intimacies serve multiple purposes in the lives of life-serving women. (Lempert never uses the term prisoners). Sexual intimacy in prison is extremely complex and, for purposes of the book, is divided into 11 distinct categories ranging from “entry sex” to “sex for sex’s sake.”

She also explores the prison culture of drugs and sex, which is especially moving in a chapter named “Juvenile Lifers as ‘Minnows in a Shark Tank’.” Lempert talks with two lifers, now in their 30s, who were teenagers when they were admitted. Lempert is especially tortured by the long sentences of juveniles in prison for life.

“By the time they are 38, they have already been imprisoned for life,” she said. “Michigan may not have a death penalty, but it does have incarceration for life.”

In the book, she also explores a class of women who use prison as a spiritual journey, with hopes of making the incarceration meaningful. She finds that prayer is the most common way women create “meaningful lives.”

She also explores through the thoughts and voices of the prisoners themselves and the complicated relationships with “good” and “bad” correctional officers. It is imperative to note that just prior to the time of Lempert’s study, correctional officers’ abusive sexual relationships with prisoners resulted in a lawsuit ending with a $15.4 million award for the victims.

Lempert’s experience in conducting the study, writing the book and meeting the women sentenced to life has made her an outspoken activist for prison reform.

“We have to recognize that redemption is possible, and there needs to be second chances,” she said. “We can’t just throw people away in order to extract vengeance. Vengeance seems to be the reason we punish people far longer and punish them harder.”

Lempert is also adamantly opposed to private for-profit prisons, which she says “have to be filled.”

In our conversation, Lempert reflected on her time as an undergraduate at Michigan State University in the 1960s (she graduated in 1966) and its impact on her concept of social justice. She recalled the Civil Rights movement on campus and MSU’s over-reaching restrictions on women.

“If you tried to it to young women today, it would be like explaining painting on cave walls.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here