Bottoms, Lansing Symphony make red-hot case for live music

The spectacle of four tympani players, thundering away like a runaway chariot at the end of Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique,” was one of a thousand arguments for getting out of the house and surrendering to the glories of live music at Friday’s Lansing Symphony season opener.

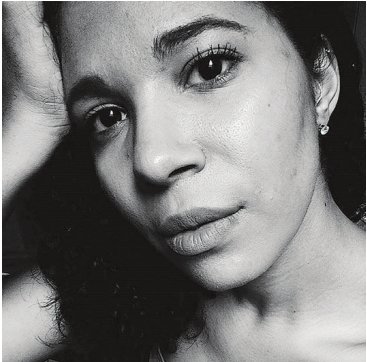

Another one was mezzo-soprano Amanda Lynn Bottoms, who pushed a ravishing performance of music by Spanish composer Manuel de Falla into the red zone.

Bottoms has a rich, molten voice that surges from below, like a magic magma from deep in the earth, a smooth and surging substance that glows but doesn’t scorch.

Whenever she sang, I found a second pair of ears, at about hip level, attuned to a secret southern hemisphere of purple sound.

Falla’s music is right in the sweet spot of mid-20th-century energy, sleekness and beauty, where Music Director Timothy Muffitt and the orchestra really seem to thrive, with dance rhythms spilling all over the place, sophisticated piano touches and gorgeously shifting patterns and textures.

In one segment, the “Dance of Terror,” Bottoms flung astonishing streamers of trans-verbal, bone-chilling melismas on top of a stupendous maelstrom of rhythms and colors, evoking a drunken but lucid madness, a scary but beautiful crack in reality.

There’s little to say about the night’s opener, an obscure overture to an 1828 opera about a vampire. The music stuck firmly to the musical conventions of 1828 and got a fine, workmanlike reading from the orchestra, although, for all I could tell, the subject could just as well have been a poor fellow who lost his candle snuffer as a blood-sucking creature of the night.

Friday night’s massive closer, the hour-long “Symphonie Fantastique” by Hector Berlioz, has to be heard live to be fully appreciated — if only because most recordings have to compress the extremes in volume to keep your sound system from exploding.

Muffitt and the orchestra, of course, faced no such limitations. The sudden fortissimos in the climactic movements were truly shocking, as in a nightmare, when the monster chasing you from a mile away suddenly appears in front of your face. (The Falla also featured sudden, demonic fortissimos, a dramatic, foregrounding effect that never come off as well in recordings.)

For all its lurid backstory of opium-fueled fever dreams, the Berlioz symphony is pretty tame, bordering on dull, for much of the running time. But it’s important to dare to do dull now and then. The payoff is substantial. You can’t cut right to the beheadings and orgies and expect them to have the same effect.

That’s another great thing about live concerts — no surfing or flipping. You’re stuck. You have to settle in and wait for the train to roll in on its own good time.

Knowing this, Muffitt took his sweet time with the light-textured, drifting reveries of the first movement, shaping them lovingly as they coalesced into a counterpoint of melodies and fugues. It was time for the strings to hold the hall, and they sounded splendid.

The heavy ordnance lay in reserve.

The tubas sat, bells to the floor, like the Russian guns at Borodino, waiting for Napoleon.

The second movement, depicting a waltz at the ball, brought everybody’s blood pressure down even further. The relaxed air reached sublime levels with the next movement’s opening duet between an English horn and oboe, representing two shepherds.

Sneaking offstage to heighten the effect, principal oboist Stephanie Shapiro traded ethereal melodies with her section mate, Gretchen Morse, while the rest of the orchestra looked on, and the audience went into half-lidded bliss, like a belly-scratched dog.

Berlioz is no Ravel or Tchaikovsky — his melodies have the best intentions and make all the right turns, but they’re far from inspired. That’s why it was crucial to have soloists on hand, especially in the woodwinds, who poured so much juicy life into the music — especially Shapiro, Morse and principal clarinet Guy Yehuda, who had a long, fine utterance in the third movement that could have been — and often is — a complete yawner in less passionate and competent hands.

Lulled by all the waltzes, shepherds and whatnot, the audience was in perfect condition to be blasted out of its wits by the merciless whacks of the “March to the Scaffold” and the wild music that follows. But the thunder and drama were secondary to the meat of the experience; superbly crafted and paced music-making with no detail, no melodic line or gesture, left unloved.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here