For years, residents and politicians have heard the Red Cedar project is just a month away; shovels would be in the ground by spring. But finally, after nearly six years, the decommissioned Red Cedar Golf Course is at the center of a development economic and political leaders call “transformative” for Michigan Ave.

“It was a tough negotiation,” said Bob Trezise, CEO and president of Lansing Economic Area Partnership and key negotiator on the deal. “We had one united front. ‘Do what’s best for the city.’” And it did. The initial proposal from developer Joel Ferguson was pegged at $380 million and included a large Sparrow Hospital professional building to complement housing, hotels, restaurants retail shops. It would have required the city to underwrite at least $38 million in bonds to construct the massive concrete platforms needed to build above the Red Cedar River floodplain in addition to tax abatements and other incentives. Developers would have paid the city $7.5 million for the property.

The new, more modest plan, moving forward without Sparrow, requires the city to issue only $10.7 million in bonds to defray just over $77.9 million needed to build infrastructure platforms to mitigate flooding. Now, developers will pay $2.1 million for the former golf course.

During 6 years of negotiations, Ferguson and his partners, first Leo Jerome and later, Frank Kass, pushed the city for more concessions than it and LEAP were willing to offer. They tried to convince Ingham County to subsidize some of their project. That approach also failed.

The process frustrated all parties. Lansing Mayor Virg Bernero moved it along but ultimately left office without accomplishing what could have been his crowning development achievement.

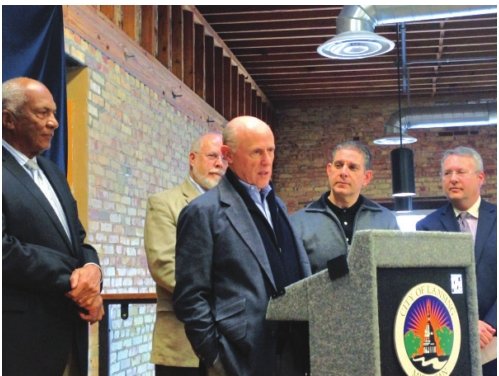

Andy Schor stepped in. “We asked everyone to come to the table,” said Schor, who took office as mayor on Jan. 1. “We said, ‘You’ve been working on this for four years. There are disagreements.’ I had people who wanted me to just rebid the whole project. I said, “We’re four years down the road.” We’ve put a lot of city dollars and hours into this. The developers put a lot of money into this. Let’s get to the table and see what the issues are.”

Schor said it turned out there were fewer issues preventing a deal than he originally thought.

“We thought we had a deal in early November,” said Trezise. “We thought we were a week away from announcing it. But then they rejected the proposal and went ice cold.”

Ferguson and his team didn’t come back to the table until mid-December, Trezise said. And the deal that was inked between the city and the developers “had no substantial changes” to the November draft.

Negotiating with Ferguson and his team was over small details at the end, Trezise said. For example, as with other development deals, the developer as a matter of course pays the city for its legal expenses incurred in putting together the deal. Trezise didn’t have a final number on that cost, only that it was “at most a couple hundred thousand dollars,” but Continental/Ferguson didn’t want to pay that. Under the terms of the signed agreement, they are paying it.

Bernero extolled Tresize and two top aides, Randy Hannan and Chad Gambill, for what they achieved. In an uncharacteristically muted statement in relation to the process and final deal, he said, “I am extremely proud of my entire team and the extraordinary work they did to position the Red Cedar project for success, while protecting the best interests of Lansing taxpayers and ensuring that the final product meets the high expectations and standards we demand.””

“We drove a hard bargain and secured the best possible deal for the city and its residents. I make no apologies for that and look forward with great anticipation to this transformational development finally coming to fruition and sparking even more economic development along the vital Michigan Avenue corridor.”

The project would include a 130-room full service hotel, costing $29.7 million; a select service hotel, with 120 rooms costing $25 million; 40,000 square feet of retail and restaurant space costing $9.1 million; 170 market-rate apartments costing $19.3 million; 1,248 beds of student housing costing $55.5 million; and a 112-unit long-term assisted living facility costing $25.5 million. That’s $164.1 million.

Including the costs to for the integrated parking structure, which is the platform on which the development will be built, the cost will be $242 million, developers and economic development officials said. The program will also create an estimated 388 permanent fulltime jobs once it’s complete. An added bonus to this will be income tax captured by those living in the market rate apartments and the student housing.

The terms of the development agreement includes a possible Brownfield Tax Increment Financing deal for the developers. Under such a deal, they pay the new, higher property value to the city based on the new development. However, that money is then used to pay back various expenses incurred by the developers including the city issued bonds, which get paid first; and any environmental remediation costs done to clean up the site.

“They have a lot of incentive to keep on schedule,” said Trezise of the developers. “If they don’t, they are on the hook for costs and not seeing their investment paying back.”

He characterized the deal as having one carrot for the developers and “nine sticks” of enforcement choices for the city.

Schor said, “Any incremental taxes that come in on that property, which includes not only our taxes but state taxes, county taxes, everybody who is making increased tax dollars comes in to pay for that. If there’s not enough to pay for it, the developers have to pay the city’s share,” said Schor of the deal involving the city issued and backed bonds. “There is not one tax dollar on the hook here. If we do nothing, there are no increased tax dollars. If we do this, you have increased property taxes that help to pay the bonds plus you have increased city income tax, so the city is making money.”

Schor said he anticipates criticism that the city could have gotten more for the property, which was assessed at more than $7 million. But he contended the overall shape of the deal, particularly that the city has a big say in what the final result will be, is worth the tradeoff.

Trezise said the negotiations over the repayment of the bonds took “two years.” Indeed, Ferguson and Trezise even approached the county to underwrite and issue $35 million in bonds.

The thinking was that the county’s higher credit rating would save millions in interest payments.

But county officials rebuffed the move, sending a laundry list of requirements and documentation before they would even enter into negotiations over the idea of issuing the bonds. Those demands were never met and the developers stuck with negotiating with the city.

At the same time this Red Cedar project is being constructed, Ingham County Drain Commissioner Pat Lindemann will be revamping the Montgomery Drain, which flows through the former golf course. While Trezise and the developers said the two projects were separate and not reliant on each other, the development agreement requires the drain plans be “substantially completed” before the construction can proceed.

Also hanging over the project is a lawsuit brought by Leo and Christopher Jerome. The Jeromes originally proposed the Gateway Project and were selected by the Bernero administration. Ferguson was brought in by the Jeromes, who had no experience with a large-scale development like the one they proposed. It would have included similar mixed use buildings, but it would have spanned across Michigan Avenye to include the former Story Olds property where SkyVue is.

The partnership between the Jeromes and Ferguson soured.

Ferguson said that was because Christopher Jerome was “making unrealistic demands.” Among them, he wanted to be the project manager as well as be given a housing and car allowance.

As a result,Bernero retracted the deal with the Jeromes and blessed a Ferguson Kass union. The Jeromes sued Kass, Bernero, Ferguson and others in Chicago. That lawsuit was booted by a judge there. So the father son duo hired former Michigan Republican Attorney General Mike Cox to represent them in a federal lawsuit in Grand Rapids. That suit, which is still being litigated in federal court, accuses Ferguson, Kass and Bernero as well as others of racketeering among other things.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here