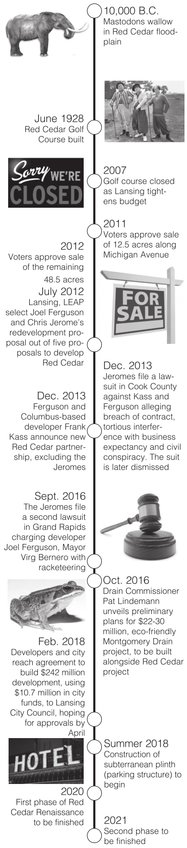

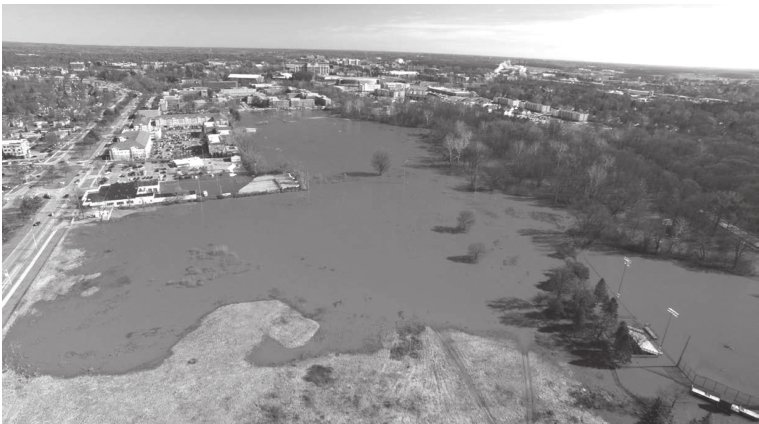

Last week, an orange kayak floated across the icy water flooding the former Red Cedar golf course on the eastern edge of Lansing, near MSU.

The man beached his tiny craft, scattering a few ducks. Two years hence, at the same spot, guests will pull up to a high and dry hotel, if the most long-awaited development agreement in Lansing’s history, announced last week, is approved by the city.

Make that two hotels, five restaurants, 170 family housing units, 112 assisted living and memory care units, 1,248 beds of student housing, and village-esque amenities such as an amphitheater, an ice skating rink and a “main street.”

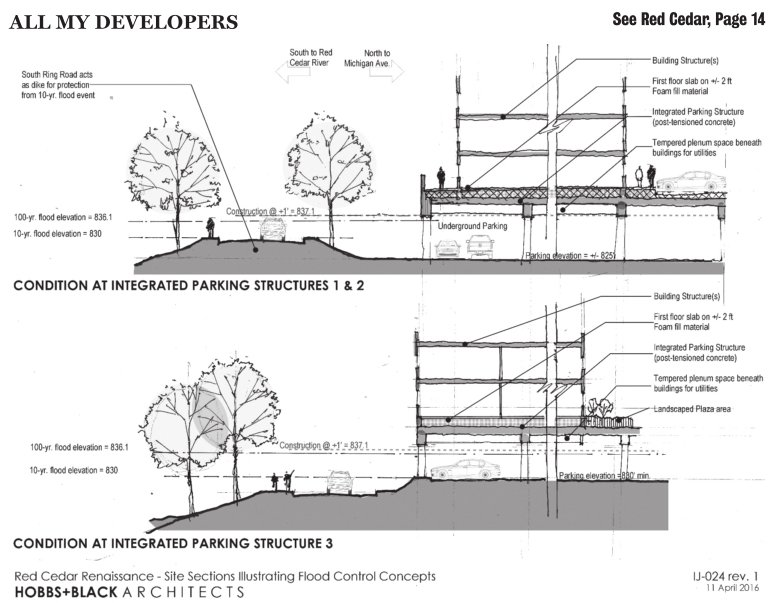

It will cost $77.9 million out of the estimated $242 million cost of the Red Cedar Redevelopment project — sometimes called Red Cedar Renaissance — just to get the ground ready. Engineers have come up with podium-like parking structures that hold hundreds of cars, channel storm water and, most important, lift all those college kids and old folks and casual diners and everything else above the floodplain.

In God’s name, why bother? One thing alone has drawn city officials and developers for more than five years to move heaven and earth — but mostly earth — to plant one of the biggest projects the city has ever seen on a few forlorn, frequently flooded former fairways.

In God’s name, why bother? One thing alone has drawn city officials and developers for more than five years to move heaven and earth — but mostly earth — to plant one of the biggest projects the city has ever seen on a few forlorn, frequently flooded former fairways.

It’s the classic real estate formula — location, location, location — times 10 thousand.

In developer-vision, Red Cedar is a cosmic wormhole — or at least a doggy door — between two hitherto unbridgeable worlds.

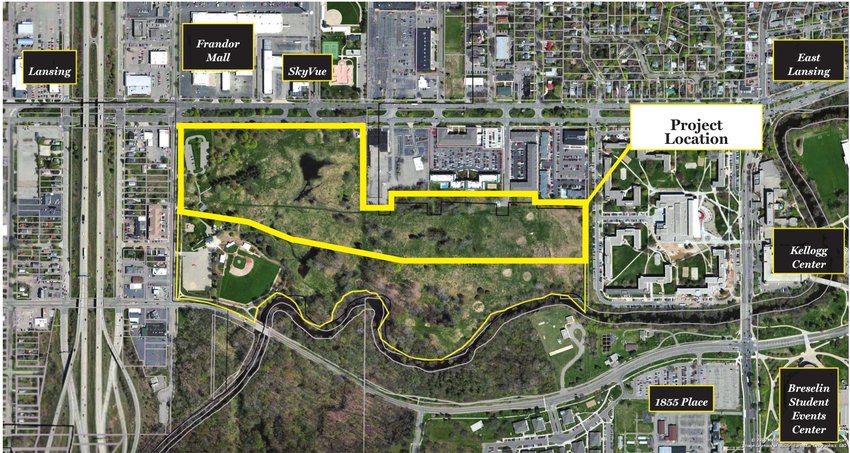

The prospect of people living, doing business and recreating by the thousands, smack dab at the border of Lansing and East Lansing, at the midpoint of the Michigan Avenue corridor linking MSU to Michigan’s Capitol, has kept the project alive through years of delays, lawsuits and logistical holdups.

About 22 acres out of the 61 are in a floodway, where nothing can be built, and will remain a park, maintained in perpetuity by the developers. The parks board will review the evolution of the park and use the $2.2 million from the sale of the property for city parks.

Paired with the epic Montgomery Drain project — an overhaul of storm water management and environmental engineering scaled to Roman aqueducts and the hanging gardens of Babylon — Red Cedar is a project like no other in the area’s history.

BELT OF BLAH

For decades, Lansing has suffered from Columbus complex, an unseemly green and white envy of the bustling corridor from Ohio State University campus to the Ohio state Capitol.

The Red Cedar team even brought in a Buckeye with megabucks, Columbusbased developer Frank Kass, in 2013, to show how it’s done.

“Our company has always tackled transformative projects, in Columbus, Pittsburgh, Toledo, Nashville, Charlotte, and now in Lansing, that make a longterm difference,” Kass said. “We have been a big part of everything going on in the connector, High Street, from downtown to Ohio State. This all fits our M.O. has been and that’s why we like it.”

Beginning in the 1980s, the River Trail pioneered a non-motorized link between Lansing with East Lansing. But the landward, Michigan Avenue route remains a jumble of barriers, from chain link fences around the old golf course to the dusty I-127 overpass.

A wasteland of grim east side business (eczema and hair loss remedies, sweeper repair, instant cash) have done little to enhance the belt of blah between Lansing and East Lansing.

A 2009 study by MSU’s School of Planning, Design and Construction said the corridor “is not meeting its full potential,” calling it “unattractive” and troubled with “dysfunctional land uses.”

Revitalizing the Red Cedar Golf Course and the Frandor shopping center across the street was one of 10 key recommendations in the report.

A 2004 study by a former city parks board chairman and longtime urban planning wonk, Rick Kibbey, for the Allen Neighborhood Center said a “gateway” image for the corridor will be essential to its success. Former Lansing Mayor David Hollister used the same word.

“The potential for making that a gateway and connecting MSU to the Capitol would be a dream fulfilled,” Hollister said.

Hollister said he dreamed of doing something special with the area for “15 or 20 years.”

“We were never able to get that stretch,” Hollister said. “We took care of the sin strip downtown. We moved the marker. We cleaned up down to Sparrow Hospital. My dream was to have that developed all the way to the university.”

“That area is a wall, a major gap,” said Bob Trezise, president and CEO of the Lansing Economic Area Partnership. “Not a lot of people east of that gap are willing to keep moving down the road into the city.”

By packing thousands of residents, acres of maintained parks and the buzz of hotels and restaurants into a resurgent Red Cedar, the city saw a chance to activate the energy potential of other Capitol-to-college corridors in Madison, Wisconsin, and Kass’s stomping grounds, Columbus.

To raise the ante, the moribund Sears store across the street from the golf course, where developer Pat Gillespie owns the land, is likely to free another of the corridor’s most conspicuous parcels soon.

“It would really blow up that corridor if Sears goes away and Pat’s able to step in and build a cousin-type development across the street,” developer Christopher Stralkowski of Ferguson Development said. “Now you’d have bookends as you are coming through.”

But the road to Red Cedar has been an unusually long one for Kass, a wealthy man with a private jet, a yacht and a penchant for doing big things fast.

“I’ve never spent this much money on the front end of a project and I’ve never taken five years,” Kass said. “It’s not anyone’s fault other than nature — the terrain, the flood plain. But LEAP has stuck with us, and the city has city has stuck with us.”

When considering places to invest such large sums as those involved in the Red Cedar project, developers like Kass look for “drivers.”

“A driver is a state capital and a major university,” Kass said. “Being across from retail is a driver. Lansing is all of those things.”

Pittsburgh’s Waterfront, a billion dollars’ worth of developments completed by Kass’s company in 2004, turned a sprawling, polluted former U.S. Steel works into 2 million square feet of retail, restaurants, hotels, offices and apartments on two miles of the Monongahela River, with pedestrian walkways to the river.

“Frank’s made a major statement in Pittsburgh,” co-developer Joel Ferguson said. “That’s what he’s here in Lansing to do.” Ferguson Development is Kass’ local partner for the Red Cedar project.

Stralkowski, Ferguson’s associate and son-in-law, called Kass’ Pittsburgh project “a classic example of how to do urban riverfront development.”

When it came to taking on the Red Cedar project, Kass said “no” before he said “yes.”

It’s a long soap opera. Sometime before 2012, Leo Jerome, owner of the Story Olds dealership on Michigan Avenue, and son Chris contacted Hallmark, a student housing company affiliated with Kass. When Oldsmobile went the way of the passenger pigeon, the Jeromes saw a chance to scrap the dealership and put up student housing close to MSU.

The Jeromes had longstanding ties to Lansing and Michigan Avenue, but little experience in development.

“We had no trust at all that they had any idea what they were doing,” Kass said. “These guys never developed anything. Chris Jerome couldn’t run a Lionel train. I said no.”

Kass was out of the picture temporarily, but his personal jet will return shortly.

A partnership with Ferguson made more sense for the Jeromes, at least at first. Leo Jerome met Ferguson in the 1970s, when Ferguson was a teacher and about to become the first African- American, and the youngest person, to be elected to the Lansing City Council. Ferguson visited the Olds dealership on occasion, eating chicken soup out of a cup for lunch in the lean times before he drove a Bentley.

Leo Jerome recalled in 2012 that Ferguson bought an Oldsmobile but ruined the engine because he never changed the oil. “I changed the engine and we became friends for life,” Jerome said. “The relationship has been there for over 50 years.”

The cast of characters in the Red Cedar drama kept growing. Throw in Mayor Virg Bernero and Drain Commissioner Pat Lindemann, Jerome said in 2012, and “we’re going to have to have meetings in Spartan Stadium to accommodate all the egos.”

As things turned out, the Colosseum might have been better. The Jeromes were heavily invested in the project and felt proprietary about it. “People with their eggs all in one basket typically get things done,” Chris Jerome said.

According to Stralkowski, Chris Jerome demanded a corporate credit card, a car allowance, a $1,000 housing allowance, and, most important, voting rights for himself and Leo — meaning Ferguson would be voted down two to one whenever a disagreement came up. Ferguson, an accomplished housing developer, member of the MSU Board of Trustees and civil rights pioneer in Lansing, had no interest in taking a back seat.

In Stralkowski’s account, Bernero walked into a December 2012 meeting with a baseball bat, demanding that the parties reach a deal, but they split up anyway.

Meanwhile, Ferguson and a banker pal, John McCoy, were zipping off to Las Vegas now and then with Lansing lobbyist Gregory Eaton and another friend, Ohio meat mogul Michael Bloch.

Bloch was the lightest of a trio of heavy hitters. (Michael’s Finer Meats & Seafoods is a massive meat and seafood processing operation with a 2, 700-gallon tank that holds a ton of live lobsters.)

Ferguson met McCoy in 1993, when both men served on the board of Freddie Mac. McCoy had impressed Ferguson with his acumen at Chase Bank. “He took them from $7 billion to $187 billion in assets,” Ferguson said.

President Bill Clinton appointed Ferguson to the Freddie Mac board after lobbying him, unsuccessfully, to be the U.S. ambassador to Jamaica.

Ferguson said he’s fine with missing out on Jamaica because he met McCoy, who, as it turned out, went to kindergarten with Kass.

‘We believe we’re tearing down walls’

-Lansing Area Economic Partnership CEO Bob Trezise

In 2013, Ferguson and McCoy went to Scottsdale to attend a surprise birthday party for Bloch.

Two days into the party, Ferguson and Kass found themselves at the same table and hit it off.

Soon after, Kass flew his jet to Lansing, met with Ferguson and embarked on their Red Cedar adventure.

The new partnership, dubbed Continental/Ferguson, was announced in 2013. Mayor Virg Bernero praised Kass’ team as “deeply experienced in mixed-use projects and urban revitalization, including riverfront developments.”

“We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to get it right,” Bernero said. “We believe we have found the best possible partners.”

But the split between the Jeromes and Ferguson churned up some white water. In September 2016, former Attorney General Mike Cox filed a federal lawsuit accusing, among others, Ferguson, Bernero and Trezise of racketeering, contending they were improperly cut out of the project as a reward from Bernero to Ferguson for political favors.

The suit is still tied up in federal court, but a pre-motion hearing in February 2017 did not bode well for Cox and the Jeromes. U.S. District Judge Janet Neff lambasted the plaintiffs for a rambling complaint full of “irrelevant, conclusory statements” and “stream of consciousness” passages that “appear to be an outpouring of emotion and anger.”

“If I were in your shoes,” Neff told Cox, “I’d probably go south somewhere and put my head in the sand.”

The lawsuit still isn’t settled and the drama of Red Cedar’s changing dance partners isn’t over yet. As a longtime member of the MSU Board of Trustees, Ferguson’s stock in the Lansing and MSU community plummeted considerably in early 2018, in the wake of the Larry Nassar sexual assault scandal.

The trustees have been assailed for the scandal and its aftermath, a tire fire of sordid behavior and official mishandling that has drawn ugly attention to MSU around the world. Ferguson’s comments disparaging victims and minimizing the scandal as “that Nassar thing” provoked calls for him to be removed from the board.

Kass took the long view in an interview last week.

“We’re not in this for the short term,” Kass said. “We’re not going to have anything open for another two years, and this will have all sorted itself out long before then. People draw parallels between this and the crisis at Penn State, and Penn State seems to have recovered fully from whatever they went through at that time.”

Ferguson’s comments in this story come a Jan. 18 interview, before calls for him to step down reached their zenith. At a more recent meeting with City Pulse about the project last week, Trezise, Stralkowski and city development director, Brian McGrain were present, along with Kass (by phone), but Ferguson was absent.

“Joel has another role in the community, and he’s focusing on what he needs to do as a leader at MSU,” Trezise said.

His name was only mentioned at last week’s meeting as half of the Red Cedar developing entity, Continental/Ferguson. Even then, Trezise seemed to minimize Ferguson’s role.

“Well, Continental is the majority holder of the company, substantially,” Trezise said.

EMPIRE

With Kass on board, the Red Cedar project took on a solidity and national heft that helped it weather the delays and financial wrangling to come. (For a detailed look at the developers’ negotiations with the city, see related article on page 16.)

Continental, the master developer, has assembled a blue-chip portfolio of “operating partners,” all new to Michigan, each of whom will run its own part of the project.

“Everybody uses the term ‘mixed-use development,’ and it’s become one of the worst catchwords there are — like saying someone has potential,” Kass said dryly. “Well, we actually do that.”

Each of his operating partners amount to small empires in their own right. A company with strong ties to MSU, Concord Hospitality of Raleigh, North Carolina, will run the hotels. Mark Laport, the founder and CEO of Concord, is an MSU alumnus who was named the hospitality industry’s “Leader of the Year” in 2015. Kass said about a third of Laport’s management team graduated from MSU.

The senior living portion will be run by Leo Brown Group, an Indianapolis-based giant with a billion dollars of senior living and post-acute care facilities across the nation. The apartments will be run by Columbus-based Coastal Ridge Real Estate, with about a $1.5 billion portfolio of apartments in 22 markets.

Kass said the operating partners will all “have money in this deal and will have their entire operating partnership at risk with us. That’s what they do.”

As “master developer,” Kass will build the buildings, but not operate them.

“We’ve brought a lot of expertise to Lansing and Red Cedar,” Kass said.

Trezise said Kass’ portfolio of partners was one of the reasons the city welcomed his participation in the project.

“We couldn’t do this without him,” Ferguson agreed. “He’s got the hotels and the people, the rapport with everybody, from his own reputation.”

The developers haven’t announced tenants yet, but Stralkowski predicted a mix of national “fast casual” restaurants like Houlihan’s and local restaurateurs. Stralkowski said he plans to reach out to locals like Zane Vicknair, formerly of Golden Harvest and now chef/owner of Street Kitchen on the east side, and Sam Short of the Creole and Cosmos restaurants in Old Town.

‘You’ll see smallmouth bass going crazy in that river when I’m done with it.’

-Ingham County Drain Commissioner

Pat Lindemann

Retail will be minimal, in part to avoid completion with nearby Frandor, but mostly because brick-and-mortar retail is under siege in the era of Internet shopping.

However, Red Cedar’s multi-generational “village” approach to housing is new to this area, at least on the scale proposed. At the planning charrettes for the Red Cedar project in 2012, residents of Lansing’s east side pointed out the need for housing for MSU alumni and retired staff who are empty nesters or whose spouses have died.

McGrain explained that the buzz phrase “aging in place” is commonly used for seniors who enjoy the cultural life and green space of a university campus but don’t want to maintain big houses and lawns.

“A lot of people want to stay, but we don’t necessarily have a place for them to stay,” McGrain said. “This addresses the full life cycle, from students to families to seniors.”

Unlike other big projects in the Lansing area’s recent history, such as the renovation of the majestic Ottawa Power Station and the Art Deco Knapp’s building, or the angular Broad Art Museum, Red Cedar has no architectural statement to make.

Stralkowski said the look of the buildings would be “traditional brick, glass and metal,” with “nothing trendy, nothing out of Dr. Suess,” referring to the particolored developments Pat Gillespie has built on each end of town.

The 80-foot height of the buildings facing Michigan at Red Cedar would allow for “dramatic landscape and lighting.” He said the architects are going for “a crisp, clean look” similar to the new 1855 development across from MSU’s Breslin Center.

FIREFLIES AND RESTAURANTS

If generic commercial architecture and mixed uses don’t thrill, there is one other thing, besides location, going for the Red Cedar project, and it involves large numbers of insects.

If Ingham County Drain Commissioner Pat Lindemann and the developers are to be believed, the synergy of the massive Montgomery Drain project and Red Cedar will result in a unique place that is half Eden, half Metropolis.

“The drain commissioner, and what he’s doing to the Red Cedar to help our project and all of that area, is just paramount for the success of this project,” Kass said.

“It’s an extraordinary opportunity to put private dollars to work in Lansing,” Lindemann said. “It’s an impressive attempt to upgrade Lansing by going backwards in time, trying to recreate the ecosystem and live next to it.”

In the 10 years the golf course has been idle, many local residents have come to enjoy its overgrown meadows and trees. But Lindemann, one of the state’s most vociferous environmentalists, called the park a “dead zone” ecologically, poisoned by decades of golf course fertilizers, especially where the tees and greens used to be.

“If anybody thinks that space is natural, they’re wrong. There’s nothing natural about it,” Lindemann said.

The synergy between the two projects is also practical. Lindemann likes to say they “don’t want to move the same bucket of dirt twice.”

But unique opportunities open up when two big projects are happening at the same time.

Even in the project’s early design phase, Lindemann advised the developers to position their main restaurant at a corner overlooking parkland, where fireflies lay eggs in vast numbers and put on a spectacular show in the summer.

If bland architecture fails to excite, the trails, ponds, revitalized river and other natural features of the drain project will elevate Red Cedar above most sprawling mixed use piles. Lindemann is happy to whip everyone up further.

“I’m building ecosystem niches into the system. There will be more species there than you can count,” he said. “Frogs are going to wake up the people in those hotels.”

“That’s fine with me,” Kass said. Lindemann also plans to take advantage of the presence of heavy earthmovers near the site to use a $1 million state grant to rebuild the Red Cedar River and establish fish habitat. The work would include laying gravel beds where steelhead trout and salmon can lay eggs, shaping the riverbanks to minimize runoff onto the beds, and narrowing the banks so the river would run faster and wash the beds.

CLEANING UP

The ultimate goal of Lindemann’s drain project is to clean up the Red Cedar River. To Kass, that is no mere amenity. The cleanup, he said, was “crucial” to his investment in the project.

“I’d have no interest at all in spending all this money to look at a polluted river,” Kass declared.

For decades, the Montgomery Drain’s service area has served as a vast urban toilet where rain flushes tons of runoff, from tire rubber to toxic metals to cigarette butts, straight into the Red Cedar River. The service area is centered on the parking lot of the Frandor shopping center, a flat basin that swirls with rain in summer and is piled with dirty mountains of snow in the winter. The area also includes strip malls and a subdivision to the north and the highways that pass through it, including I-127.

Lindemann estimated that the Montgomery Drain district spews between 50,000 and 75,000 pounds of pollution to the Red Cedar River each year. He predicts that his storm water “urban retrofit” project will eliminate 96 percent of that pollution.

The Montgomery Drain project will draw on the full panoply of “constructed natural features” familiar from Lindemann’s signature project, the Tollgate Wetlands — also a former golf course.

Lindemann plans to install rain gardens, retention ponds and 23 filtering waterfalls cascading from the north end of Ranney Park, under Michigan Avenue through the Red Cedar project to the river. Two and a half miles of service access paths, built for maintenance of the drain, will double as hiking and biking paths.

“When I build those ponds, you’ll see 15 blue herons down there every day,” he said. “You’ll see kingfishers and birds of prey, steelheads and salmon in the river, smallmouth bass going crazy in that river when I’m done with it.”

The drain design adds innovations like sculptural filtration walls in the Frandor Shopping Center that will double as public water fountains. (People will be able to donate to the wall and commission their own likeness, spewing clean water.)

‘Making that area a gateway and connecting MSU to the Capitol would be a dream fulfilled’

-former Lansing mayor David Hollister

A nonprofit group, Art in the Wild, with over 150 volunteers and corporate sponsors, has already raised tens of thousands of dollars to place art in the drainage district, including a flower clock like the one at Detroit’s Belle Isle, planned for the north end of neighboring Ranney Park.

Lindemann also plans to turn the floodway south of the Red Cedar development into the most natural state possible.

“We’ll create places for turtles to lay eggs. We did the same time at Tollgate. We’re going out of our way to make this a really cool ecosystem.”

Kass is thrilled with Lindemann’s plans and called it a “wonderland.”

The synergy between the drain project and Red Cedar projects extends to financing as well. About $170 million worth of new development will distribute the pain from Lindemann’s assessments a lot thinner.

“The bigger the development, the less everyone else has to pay,” Lindemann said. “If the drain isn’t accompanied by that increase in economic development, the lion’s share will be bigger for everyone else.”

MILESTONES

The city still faces “many milestones” on the way to closing on the property, according to Trezise.

Two of them will come when LEAP and the developers ask the Council to consider the brownfield and bonding proposals. The project’s financing also requires approvals from the Michigan Economic Development Corp. and the state Department of Environmental Quality.

Meanwhile, the Council will review the purchase agreement, which has to be posted for 30 days with the city clerk.

“There are multiple moments where the public and City Council will be totally engaged,” Trezise said. “There will be many meetings, many public hearings.” Trezise is hoping for approval by April 9 so construction can start in the summer.

After the long wait, the nasty business scrums, the sky-high hype and airy promises from developers, city officials and Lindemann, it will be hard for Red Cedar Renaissance to live up to expectations.

Trezise said the city could have taken the easy route and simply sold the land off for student housing, but he, Mayor Virg Bernero and others involved in the deal wanted to see a “more complicated” project, a “village” with potential to change the game on the city’s east side.

“Michigan Avenue is the backbone of our economic development vision for the city and the region,” Trezise said. “We believe we’re tearing down walls and connecting the river, the cities, the neighborhoods.”

Kass isn’t the patient type, but he said it was worth the wait to fight the floodwaters and build “what one would build on Michigan Avenue between a great university and a great state capital.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here