You don’t have to enroll at Lansing Community College to learn stuff. If you wander into the place by mistake —fooled by the drab architecture into thinking this is where you check in with your parole officer — you are bombarded by knowledge for free.

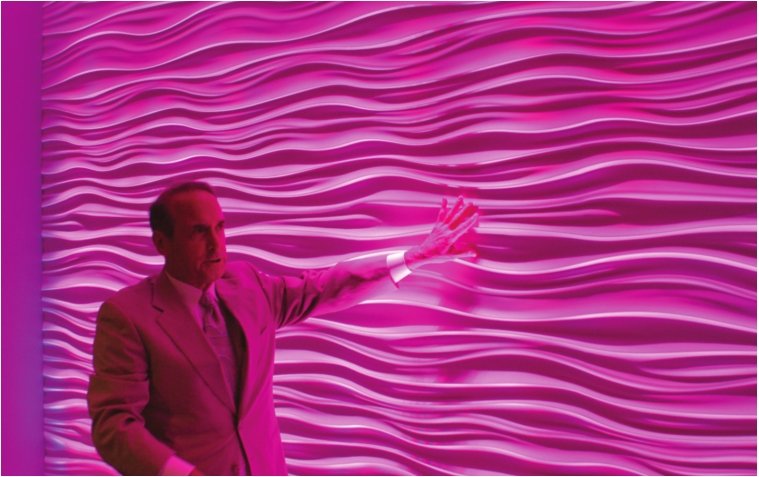

Under the “ambient learning” philosophy of President Brent Knight, no inch is left unexploited. The second floor of the Arts and Sciences Building, a typical classroom cluster, crackles with educational and artistic stimuli, from satellite photos of Syria to a giant image of the eyes of a fly to a set of photos of African-American life collected by W.E.B. DuBois.

Only one 5-foot patch of wall leaves the bare, dirty concrete and brown brick of LCC’s original Brutalist architecture untouched. But that’s a history lesson, too. It makes you curious: was this a prison back in the day?

Not exactly, but in 10 years as LCC president, Brent Knight has thoroughly fairy-dusted the entire campus with colorful sculpture, glassy atriums, trees and shrubs and plantings, a new clock tower, and on and on. Even the surface parking lots to the west, surrounded by art and greenery, don’t look like parking lots.

In April of this year, LCC’s Board of Trustees unanimously voted to extend his contract, which would have expired at the end of this year, through June 2021. His national profile has only grown since he popped up in People Magazine in 1976 as an up-and-coming, 20-something community college president to watch. In August, he was appointed to the board of directors of the American Association of Community Colleges.

LCC Trustee Andrew Abood called Knight a “miracle worker.”

“LCC has always been an important part of Lansing, but it really hasn’t functioned in the past at its full capability,” Abood said. “He has brought LCC into the 21st century, not only with its physical structures, but he deserves a lot of credit for the culture.”

Trustee Larry Meyer called him a “visionary.”

Meyer said the board re-punched Knight’s card for many reasons — but mainly for his “focus on student success.”

Meyer cited two significant programs the college has launched under Knight: the Center for Manufacturing Excellence on the west campus, where students learn robotics, precision machining and other 21st century skills, and an aviation partnership with Delta Airlines he called “unique in the nation.”

“Those are new approaches to teaching and learning,” Meyer said.

The same goes for the aggressive “ambient learning” in the halls. “We’ve got a lot of walls,” Meyer said. “Why shouldn’t it be an atmosphere for learning?”

No dye in his tie

Brent Knight is a restless man with a restless mind. He’s notorious for tooling around LCC in his golf cart to check on the never-ending campus improvements.

If you peeked at his computer history for the hour and a half I spent with him last week, you’d see images of the schools where he’s been president in the past, the Egyptian frescoes at Luxor, pictures of pickles and GM’s 1958 Futurliner bus. He can’t go five minutes without popping out of his chair, Elton John-ing his keyboard and showing you what he’s talking about.

Although Knight, 71, came of age in the stoned-out, crunchy, feelgood 1970s, the dye never got into his tie. It’s not hard to account for his getting a doctorate at 24, with no detours to find himself.

He grew up in Bay City among German Lutherans who value work above all and sold roadside produce from the abundant family farm in his youth. When he was 5 years old, he and his 8-year-old brother picked pickles in Bay County, loaded them into hundred-pound bags and took them to a pickle station to be sorted.

It sounds like exploitation, but Knight lights up at the memory. His father paid him for the work by check — usually about $3.50.

Knight jumped out of his chair to demonstrate how he lifted the check to the teller window, way above his head.

“My father wanted us to understand that if you work, you get paid,” he said.

A key boost to Knight’s education, and a big influence on his choice to work at community colleges, was getting an $8,000 Mott Foundation fellowship in 1970.

Knight interned with the president of Mott Community College in Flint and wrote his doctoral dissertation on community colleges in Michigan.

The stigma of community colleges as “Last Chance Colleges” didn’t occur to Knight, not only because of his experience with the Mott fellowship, but also because his mother went to Bay City Junior College before becoming a teacher in 1934.

“My mother did that and it worked just fine,” Knight said. “I loved the idea that everyone could go and it was affordable.”

Esther Knight, now in her 90s, gave an exuberant speech at Knight’s inaugural as LCC president in 2008. “My priority list as a parent was weaning, toilet training and reading, and sometimes the last two were combined,” she told the crowd.

Out of the box

Knight got a doctorate in business at Western Michigan University at 24. He immediately went to Triton College in Illinois to head the school’s research and grant-writing team. He was president of Triton in 1976, at 29.

That earned him an amusing blurb in People Magazine’s as a young college administrator to watch. The story mentioned that Knight owned some interesting vintage vehicles, including two GM Futurliner buses. Only 12 of the custom behemoths, the size and shape of streamlined Art Deco locomotives, were made.

Knight Googled “Futurliner” and brought up 1950s images of bulbous bus caravans deploying rooftop lights at county fairs as they displayed the products of tomorrow.

“ W e opened ours up and had volleyball parties at night,” Knight said.

But the white elephants wouldn’t fit in Knight’s garage, so he got rid of them back in the 1970s. One of them recently sold for $4 million.

“Had I just kept them,” he sighed.

After serving as president at Triton from 1976 to 1983, he was forced out in a struggle with the board over contracts and hiring, according to the Chicago Tribune.

But Knight had his fans. Sunil Chand, a former administrator at Triton and now a professor and administrator at Benedictine University in Lisle, Illinois, called Knight “the most out-of-the-box creative thinker I have ever known.”

After his tenure at Triton, Knight was president of Pierce College in Puyallup, Washington, for four years. (He fondly recalls an office that looked onto Mount Rainier.) Under Knight, Pierce bought a second campus and expanded its student base.

After four years at Pierce, Knight made a sharp career turn. He was recruited by Meijer Inc. as vice president in charge of design, construction and maintenance for all Meijer stores.

“I knew a lot on Friday and knew very little on Monday,” he said. He supervised over 400 employees, building new stores across the Midwest in one of Meijer’s biggest expansion phases.

At Meijer, Knight learned the value, in dollars and cents, of keeping an institution’s look current and inviting.

“If you remodel a store, you’ll get a double-digit increase in sales,” Knight said.

Garden interlude

After Knight spent seven years at Meijer, CEO and founder Fred Meijer took note of his skill at competing stores on time and on budget.

Meijer asked Knight to be the first board chairman of a new project, Frederic Meijer Gardens.

“He called me at home,” Knight recalled. “It was the only time he did that.”

Knight enjoyed the challenge of moving Meijer’s massive sculpture collection from the CEO’s “very nice barn” to the garden.

He remembers hustling to help first lady Betty Ford, in heels, walk down a muddy plank at the planting of a palm tree where she and her husband, President Gerald Ford, were guests of honor.

The garden went on to become the second biggest tourist draw in Michigan, next to the Henry Ford Museum. But seven years at Meijer was “plenty,” Knight said.

Another rare chance opened up when Walter Bumphus, CEO of the American Association of Community Colleges, was headed to Louisiana to start a community college campus from scratch at Baton Rouge and asked Knight to help design it.

“We started from nothing, made plans, got the money, designed and planned where to put the buildings,” Knight said.

In 2003, Knight became president of Morton College in Cicero, a troubled institution that had burned through four presidents in the previous year. At Morton, Knight made it a priority to reach out to the Latino community, about 70 percent of the student body there. In a preview of his projects at LCC, he oversaw expansions of the 1970s-era campus, including landscaping projects and even redrew the campus mascot.

Colorful sculpture, landscaping and signs have softened the campus’s Brutalist concrete architecture.

At Morton, Knight began to apply the ambient learning ideas he deployed on a broad scale at LCC, designing a Civil War themed classroom, a display on the origin of local street names and a room featuring World War II aircraft.

‘Good things will follow’

When Knight started in 2008 at LCC, a complete makeover was never feasible. But despite all the Brutalist angles and materials, the campus's organic, fluid and compact layout made it amenable to Knight’s new touches.

Judicious use of glassy additions, colorful signs and art and plantings have made a dramatic difference.

“I want the community to be proud of the college,” Knight said. “If that is the case, good things will follow.”

However, some of LCC’s faculty and staff have mixed feelings when they look at the work going on around them.

“Like any institution, I think we’re underpaid,” writing tutor Cruz Villareal said. “You’d like to see some of the money go to teachers instead of a pile of boulders.”

Villareal is a former union president of part-time LCC employees. He has three associate degrees at LCC, and makes $13 an hour as a tutor.

“Aesthetically, the college is definitely more pleasing,” Villareal said. “You can’t miss that. But what saddens is that we lose good instructors, usually as a result of compensation.”

Villareal said that because of low pay, about 40 percent of LCC part-timers stay for a year and a half or less, but that's in line with national trends. Nationwide, the average tenure of an adjunct instructor at a community college is one to three years, according to the job hunting website Insight.

Instructor Gary Affholter has taught at LCC for 18 years. He teaches reading and writing classes. Affholter said that what Knight is doing is “uniform” with what’s happening in other community colleges.

“To get students into four-year colleges or trained for jobs, that’s the goal, and he’s doing that,” he said. The makeover doesn’t sway him much, one way or the other.

“It’s very pretty. It makes it a nice place to visit, although I think students are going to go to school regardless,” he said. “I’d like to steal some of these plants and take them home, though.”

Skills gap to Luxor

Knight knows there are skeptics who think he’s gone overboard with the makeover.

“People say, ‘What’s the point?’” he said.

“You can have great programs and faculty, but in order for it to work, students do need to enroll, and they have choices. You want it to be an inviting choice.”

However, unlike remodeling a Meijer store, it’s hard to quantify the effect of a campus makeover. LCC enrollment dropped from a high of 22,126 in 2010, as the Great Recession crested, to 12,882 in 2017, but the drop is roughly in line with state and national trends.

Community college enrollments invariably spike upward during recessions and go down as the economy improves.

LCC also does extensive training under contract with area companies — 12,000 trainees in the coming year, Knight said. The contract training doesn’t show up in the enrollment numbers. In the past 10 years, LCC has done $4 million worth of contract training for 8,000 General Motors employees alone. Apprenticeships with local businesses have doubled.

The training work is a big part of the college’s next challenge — keeping up with what Knight calls “the skills gap.”

“Our aviation maintenance grads get $50,000 after two years and as many job offers as they want,” he said. “Our line worker program — line workers make even more. Twenty-five percent of all Consumers Power retirees are eligible for retirement. Companies are highly motivated to fill the skills gap.”

Knight’s vision is still shaped by his bottom-line, pickle-picking business sense, but he’s never lost his artistic side. He has enjoyed doing abstract paintings for many years, and stone and plaster sculpture is another intermittent diversion.

He smiles at the memory of a frenzied day spent making a replica of Egyptian relief carvings at Luxor, working at full speed, before the plaster dried, then staining the plaster to resemble stone.

“Let me show you the fresco,” he said.

He jumped from his chair and Googled “Luxor.”

“That was quite a day.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here