The next time you take a drink of tap water, brush your teeth or take a bath, think of the residents of Flint and Mona Hanna-Attisha, the crusading pediatrician who established the definitive link between elevated lead levels in Flint water and the poisoning of its residents.

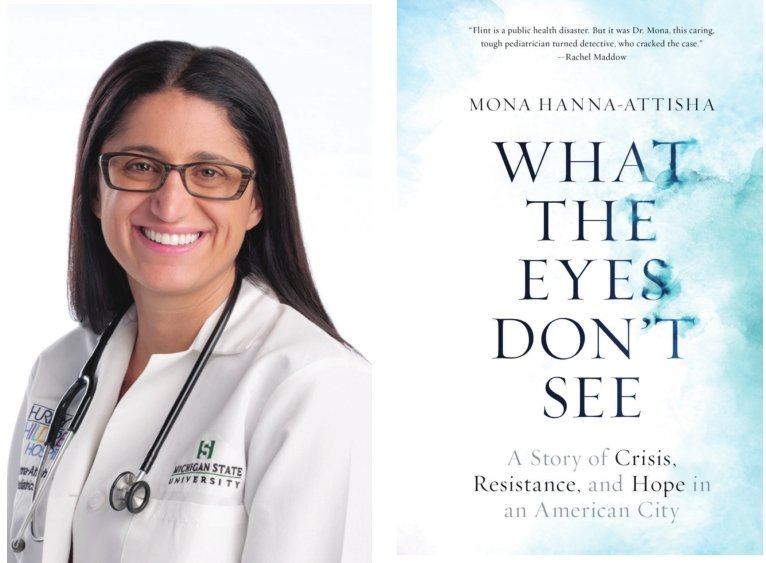

Hanna-Attisha describes her involvement in her new memoir, “What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance and Hope in an American City.”

According to Hanna-Attisha, the title of her book tells the most compelling part of the story.

“We chose to turn a blind eye to the crisis. It was about the demographics of the population. The poor, the minority, were neglected.”

In 1975, Flint had the highest per capita income of any city in the United States. Less than three decades following a pullout by General Motors, the city had become one of the most poor, dangerous and ignored cities in America.

But Hanna-Attisha said, “The situation is not about Flint, but an issue of democracy. Flint is not an isolated issue. We have to ask: What is our civic responsibility? It can’t be just for the privileged.

Are we going to have two Americas?” Hanna-Attisha was thrown into the Flint water fray by accident.

On a warm August night in 2015, Hanna-Attisha, the director of Hurley Medical Center’s pediatric division, was enjoying a backyard barbecue with friends from high school.

One of her friends, an EPA employee and water expert, told her about the unfolding water situation in Flint. Her friend explained how when Flint switched its water source, officials had failed to introduce non-corrosive chemicals into the water.

As a result, lead from decades-old pipes began to leak into the water. The friend also sent Hanna-Attisha a leaked EPA memo detailing the problem.

Flint’s financial situation became so critical that in 2011, Gov. Rick Snyder appointed an emergency manager to run the city, and in 2014 it was decided to switch the source of Flint water from a Detroit area provider in order to cut costs.

While waiting for a new source to come online, water from the Flint River was used.

When Hanna-Attisha became involved, Flint residents had been drinking the poisoned water for more than a year and had been complaining about the taste and discoloration.

They did not know that invisible to the eye, lead was now in the water.

Lead is poison. It’s as simple as that and it is especially problematic for young developing children and has been shown to cause attention deficit, learning disabilities and a myriad other problems.

The friend who had been involved in a similar crisis in Washington D.C. put her in touch with national expert Marc Edwards who became key in bringing the Flint water crisis to light.

“Serendipity brought the story together,” she said.

But it was only after a month of intensely examining and analyzing lead tests given to the children of Flint by state and local health agencies that Hannah-Attisha was able to put the final exclamation mark on the investigation. Rather than isolated cases the researched showed off-the-chart lead levels.

At a September 2015 news conference Hanna-Attisha, her pulse racing, stood in front of a crowded room holding a baby bottle and released her findings. Her message was simple — do not drink the water.

It was then her own personal hell week began and her findings were immediately assailed by local, state and federal officials. However, she stood her ground.

After Hanna-Attisha a series of media appearances, including the Rachel Maddow Show, government officials relented, accepting the facts. One week later, Snyder publicly apologized to Hanna-Attisha for the way she had been treated by his appointees.

Truckloads upon truckloads of bottled water began arriving in Flint to be used for bathing and drinking. Flint switched back to the Detroit water system, and more than a dozen state and local officials were charged with crimes in the ongoing cover-up.

Three years later, the problem still lingers in Flint. About 6,000 lead service pipes have been replaced, but there are 9,000 more to go. Many residents are still drinking bottled or filtered water and bathing at friends' houses.

Hanna-Attisha has now changed her focus to working on ameliorating the impact of lead poisoning on the Flint community — especially young children.

Her book is an intimate look at her life preceding the water crisis. The daughter of two immigrants, she was raised to understand the importance of civic responsibility and giving back.

In the book she writes: “There are lots of villains in this story.”

Fortunately, there are more heroes and heroines.

“We have to encourage folks to open their eyes,” she said.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here