The 2009 Eastern High graduate struggled with addiction, specifically meth, a popular sex drug in gay communities across the country, including here in Lansing. Saenz said he was injecting the drug, a habit that came to a crashing halt two years ago when a free HIV test registered inconclusive. In his case, the rapid test for the antibodies, which the body develops to fight invaders, was positive. But a confirmatory test taken by oral swab came back negative.

“Something didn’t feel right,” Saenz said. So he asked his primary care doctor to do a more sensitive blood test. That one came back positive.

So he asked his primary care doctor to do a more sensitive blood test. That one came back positive.

He was an elusive target for public health — the newly infected person. When someone is first infected, the virus multiplies rapidly, winning the first battle with the immune system. Eventually, the immune system gets the virus under control. Those in the very early stage, where the immune system is losing the battle, don’t test positive for the virus but are highly infectious. Scientists and doctors have found that starting someone on powerful anti-HIV medications shortly after infection can quickly control the virus and set a path to better health.

Saenz takes a three-drug combination pill every day, paid for by a publicly funded insurance program. The cost is about $14,000 a year .

“It has had no impact on my everyday routine and activity,” he said.

As the world and nation recognized World AIDS Day Tuesday, the epidemic continues at a stable rate in the U.S. The Centers for Disease Control estimates 50,000 Americans are newly diagnosed every year. Here in Ingham County the number of new infections annually has remained in the mid-20s for nearly a decade. But the good news is HIV experts believe the country could be at a tipping point to dramatically reduce and perhaps even eliminate new HIV infections without a cure or a vaccine.

The drugs that Saenz takes, and others like it, have changed what was a fatal diagnosis into a chronic but manageable disease.

Experts say those drugs plus new testing technology make them cautiously optimistic that the HIV epidemic can be halted in the coming years.

The medications — called antiretroviral medications or ARVs — have reshaped the HIV epidemic in the U.S. and other developed countries. Before they were approved in 1996, a person diagnosed with HIV faced a significantly shortened lifespan. Today, a person diagnosed with HIV who takes the drugs is expected to live a completely normal lifespan, though with a chronic manageable disease.

Scientists and public health officials have also discovered another benefit of the drugs. When a person takes the drug daily, it controls the virus — something experts call an undetectable viral load. With that undetectable viral load, a person is highly unlikely to transmit the infection.

The science behind this discovery has spawned a public health movement called Treatment as Prevention (TasP). That movement is now being driven by federal dollars to get people living with HIV into medical treatment and on the drugs. The benefits are two-fold: better health outcomes for the person with HIV and dramatic reductions in onward transmission of the infection.

Also, health officials are recommending the drugs to prevent people who are not infected with the virus from becoming infected. In 2012, the feds approved a drug called Truvada as a daily regimen to prevent HIV infection. Studies have shown that if taken daily the drug is over 92 percent effective. Using this drug as a preventative is called PrEP or Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. Truvada is the only anti-HIV drug approved for prevention, but it is also used for treating the infection.

Even the tests used to identify those with HIV have improved. The new HIV test being used can identify HIV infections as early as 12 days after infection, instead of the minimum 20 days from the last generation of tests.

Despite all these improvements, new HIV infections in the US remain stubbornly at about 50,000 new cases. In Michigan, Ingham County is second in HIV infections to the city of Detroit. Ingham stands at 175 per 100,000 people, while Detroit is at 800 per 100,000 people.

Last year, county health officials said, 25 people were newly diagnosed with the infection. About 500 people are living with HIV in Ingham County.

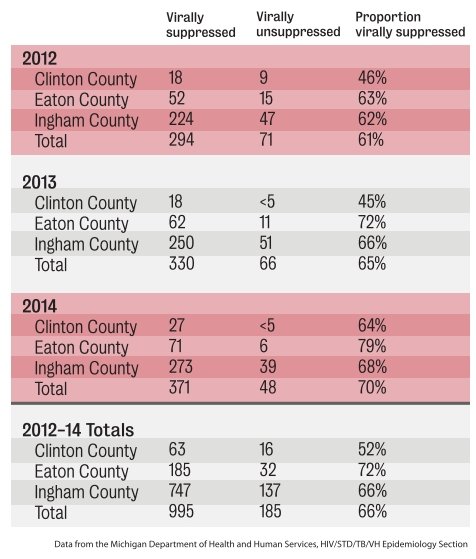

Data from the state Department of Health and Human Services show that in the last three years, the use of anti-HIV medications to control or suppress the virus to “undetectable” has grown. In 2012, of people living with HIV in Ingham, Eaton and Clinton counties, 61 percent had undetectable viral loads. In 2013, the number was 65 percent and last year it was 70 percent.

With federal funding, 82 percent of Ingham County’s 362 HIV-positive clients showed undetectable levels. That’s better than the Obama Administration’s national HIV AIDS Strategy goal of 80 percent, Ingham County Health Officer Linda Vail said.

“In general we are meeting or exceeding CDC targets,” Vail said. She said that the county was uniquely placed “to be on the front edge” of the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy — which includes access to treatment and care for those infected, and a reduction in the number of new cases. She credits the Ingham County Community Health Centers, a collaboration among state agencies, Michigan State University and Sparrow Health Systems.

“I think, absolutely, that when someone tests positive here, there is a benefit in being able to walk them across the hall to a primary care physician and HIV care,” she said.

Getting someone into care is key to addressing the disease. But that has been a struggle nationally and locally. State data show that 608 people are living with the virus in Ingham, Eaton and Clinton counties as of 2013, 431 of whom are considered in care. That’s because they have had at least one set of HIV monitoring tests done in the last year. Of those, 362 people are in continuous care, meaning they have had at least two HIV monitoring tests done in the last year. And 308 of those people are virally suppressed. This is what is known as the treatment cascade and complicates controlling the disease in the community. Those not in continuous care and virally suppressed are more likely to transmit the infection. Those who do not know they are infected are even more likely to transmit the virus. In comparison to other metropolitan areas, Ingham is doing a passable job in overcoming this obstacle.

To get more people into care, the county Health Department will be contracting with the Lansing Area AIDS Network to bring in an early intervention specialist. That specialist will focus on identifying those people who know they have HIV, but are not in care.

That sounds simple enough, but state health officials acknowledged in interviews that the state’s strict confidentiality laws about those infected with HIV could be hampering those efforts. State health officials said they are prohibited from sharing that information with community partners, such as LAAN, by state law, but they are working on a legal work-arounds to address that.

On the prevention side, the advent of PrEP, the two-drug in-one pill drug called Truvada— a daily day pill to prevent HIV — has been hailed nationally as a “game changer.” But the reality on the ground has been different. Only one in three primary care physicians and nurses is aware of the intervention, Vail said.

“We need to get our infectious disease doctors out in the community doing grand rounds,” Vail said. “They are key to informing other doctors about PrEP. And I think they will be doing that.”

Vail reports that Ingham County Community Health Centers’ doctors have prescribed PrEP to about 50 people.

INSURANCE STATUS

The combination of Treatment as Prevention (TasP) and PrEP is working in San Francisco. That city saw only 302 new HIV infections last year. That’s the lowest it’s been since the test was for the virus was first made available.

By scaling up access to treatment, in 2014 half of the diagnosed people living with HIV in the city had undetectable viral loads.

Combine that with the scale up of PrEP for the stunning reductions.

A study of 657 men who have sex with men using the preventative intervention of PrEP found zero new infections among those men. That model has won praise by national HIV experts.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease, told The New York Times earlier this year that he “loved” the model.

“If it keeps doing what it is doing, I have a strong feeling that they will be successful at ending the epidemic as we know it. Not every last case — we’ll never get there — but the overall epidemic. And then there’s no excuse for everyone not doing it,” he said.

That model is not without critics, however. The study of PrEP use saw half of the participants diagnosed with another sexually transmitted infection — an indication those men were not using condoms. But Vail said that is likely a consequence of the PrEP protocol, which requires quarterly STI testing.

The San Francisco model may not be fully achievable in Michigan. Treating HIV is expensive — the cost of drugs alone runs tens of thousands of dollars a month. PrEP costs $12,000 a year, or $1,000 a month.

“ACA implementation has expanded insurance options for thousands of People Living With HIV,” said Dawn Lukowski, acting manager of HIV care and prevention for the state of Michigan. “However, premiums, deductibles, co-insurances, and co-pays can still be prohibitive and present a barrier for low-income PLWH who cannot afford even the reduced costs. Therefore, services like ADAP, health insurance premium and costsharing assistance, targeted testing, emergency financial assistance, etc. are all still essential to filling financial gaps left by ACA.”

State officials also announced in October they have received a three-year grant to develop a pilot project to promote PrEP in Detroit. The first payment for the grant was nearly half a million dollars. If successful, state health officials believe the lessons learned and the educational outreach programs developed in Detroit can and will be rolled out statewide.

For Vail, the county’s health officer, the county can do more. While she has only been at the helm for about a year and half, she said she wants to develop a countywide HIV strategy to bring the various “pockets” of knowledge together.

“I think we can do more as a department,” she said. “One strategy has the potential to have a greater impact.”

For more on the HIV epidemic, see www.lansingcitypulse.com.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here