Last Tuesday, the day before his first round of chemotherapy, Bob Alexander went through a stack of papers at his Lansing condo.

In late January, Alexander was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He was in a mood to look back, or at least he pretended to be, but his excitement over the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries kept distracting him.

"Hillary is so namby-pamby,” he said. “Bernie says $15 minimum wage, she says, 'I'll do $12.' Bullshit. Just atrocious. She's in la-la land."

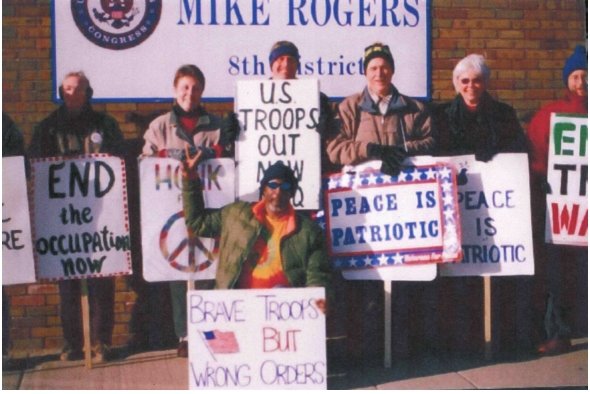

He pulled out a picture of himself, standing with Iraq war protesters outside the office of U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers, who pummeled Alexander in two runs for U.S. Congress in 2004 and 2008.

The photo is strangely comforting. It says all's right with the world, even though nothing is right. In the 1990s and 2000s, while toothy flag-wavers like Rogers settled into the national driver's seat, Alexander was in his element, two feet outside the window, in the cold, the shrubs and the dog shit.

He padded to the kitchen for a glass of water. The diagnosis hit Alexander when many of the issues he's hammered all his life — income inequality, racism, access to health care — have spectacularly come to a head.

"A lot of us older folks have a lot of understanding about this kind of stuff, but we didn't have the ability to motivate young people to get on our side," he said. "They saw politics as evil. They just didn't want to get involved. This Bernie Sanders campaign has eliminated that wall, and it's just amazing."

Almost everyone in Lansing, and half the state's population, have run into Alexander over the past 40 years. He's managed dozens of campaigns, worked for hundreds of Democratic candidates, circulated thousands of petitions for causes ranging from legalization of marijuana to physician-assisted suicide.

"Bob has never been cynical. That's the beauty of him," former Michigan state senator Lana Pollack said. Pollack has known Alexander since the 1970s. In 1982, Alexander pulled out of the state Senate race because he thought she had a better chance to win. It wasn't the only sacrifice play of his career.

Political consultant Mark Grebner com pared Alexander to a lighthouse. A longtime Ingham County Commissioner and fellow policy wonk, Grebner has known Alexander since 1972.

"He's part of the navigation of the Democratic Party," Grebner said. "He's fixed. He refutes Einstein's theory of relativity."

Beto Alejandro

Growing up in Berkley, a suburb of Detroit, Alexander read a lot of history. He spent hours drawing elaborate maps, including a panorama of the battle of Gettysburg he still recalls with pride. In the early 1950s, he watched his father work with a neighborhood association to organize the fight against Dutch Elm disease. He and a friend got $3 apiece to deliver notices to 285 houses. He still remembers the names of the streets and number of blocks they covered. It was his first leafletting campaign.

"We had to fold them very carefully," Alexander said. "My father said you have to have respect for the people you're giving them to."

Political activism didn’t interest him much, even after graduating with a history degree from the University of Michigan in 1966. The only door-to-door canvassing he did in college was to help the university put a stop to panty raids.

He thought about law school, but the Vietnam war was heating up fast. He joined the Peace Corps and spent two years in India, working in intensive chicken breeding, but the draft loomed even larger when he got back in 1968. He applied to the National Teacher Corps, a Great Society program that sent young teachers to poverty-stricken areas.

The Peace Corps expected 5,000 applications. It got 27,000. Alexander didn't make it and was due at the draft board Aug. 2. In late July, he learned that Congress had authorized three more Teacher Corps training sites. The closest was in Bowling Green, Ky.

His parents dropped him off at the corner of Telegraph and 12 Mile roads with a duffel bag and a sign: "Bowling Green or Bust."

He ended up teaching middle school in newly desegregated Hopkinsville, Ky., 70 miles west of Bowling Green, near Fort Campbell, a huge army training camp. When the one-year gig ran out, he drove to Detroit June 19, 1969, to apply for another Teacher Corps opening.

"That's when I just blossomed," he said. He taught at Webster Elementary, at 25th and Porter, near the Ambassador Bridge, where 40 percent of the kids spoke Spanish and there were no Spanish-speaking teachers.

The area was in political ferment, with Hispanic/Latino protest marches to the Board of Education building. Alexander was in the thick of it, under the cognomen Beto Alejandro. He fell under the spell of future Detroit mayor Coleman Young, then a hardcharging state senator who gathered input at annual legislative conferences and monthly task force meetings.

"I just sat here and soaked it all up," he said. "People longed to be there, to be part of this boiling pot of ideas."

In March 1971, Congress gave 18-yearolds the vote. That May, the Supreme Court ruled it was unconstitutional to keep college students from voting in the city where they went to school. The influx of young voters was a game-changer for activists seeking office.

Alexander moved back to Ann Arbor and got involved with farm workers' groups, the Human Rights Party, "about 10 different things." He dismissed the Democratic Party as too "status quo," but his relationship with the HRP wouldn't last long.

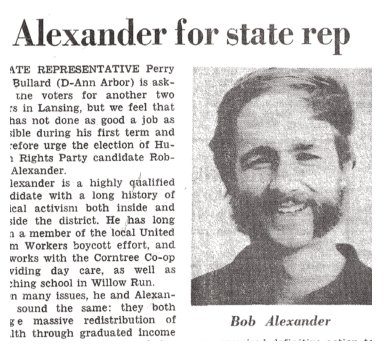

He learned a big lesson in his first bid for public office, running for state representative in liberal Democratic icon Perry Bullard's district in 1972.

"Perry Bullard was a big deal," Grebner recalled. "Bob very nearly defeated him as a third-party candidate, sucking off enough of the vote to elect a Republican. As a reaction to that, Bob spent the rest of his life deploring third-party runs."

"I did my little tour with the Human Rights Party and Doc Spock," Alexander said. (Dr. Benjamin Spock, the renowned baby doctor, was the HRP's 1972 candidate for president.) "I was done trying to create a new national party. That was the end of my personal running for awhile."

In the years following, Alexander gravitated toward brainy, compassionate, unorthodox Democratic politicians. In 1974, he ran Democrat Zolton Ferency's unsuccessful campaign for governor against Republican George Romney. They lost the election, but Alexander gained a dear friend and mentor. He loved driving Ferency and his wife, Ellen, all over the state, listening to "Zolie's" stories about the Russian front in World War II. "I had a tremendous rapport with him," Alexander said. "Zolton was — and Ellen still is — just a gem, so real."

In 1976, Alexander got involved in the populist presidential campaign of Fred Harris, a former Oklahoma senator who tooled around the nation in an RV and stayed in supporters' homes to save money. (Harris gave his hosts a token for a night in the White House in return.)

"He was brilliant," Alexander said. Several of Harris' books, with titles such as "Locked in the Poorhouse" and "Deadlock or Decision," still sit on his shelves. "They're just as accurate now," he said. "Bernie [Sanders] is the Fred Harris of today."

Against his better judgment, Alexander loaned the campaign $2,400 of his own money for a big fundraiser. Harris had the support of the Service Employees Union and plenty of three-figure donors were lined up, so he was sure he'd get his money back. On the day before the event, Harris dropped out of the race. He was screwed.

"I learned a very expensive lesson in that campaign," Alexander said. "If you're getting into left-wing politics, running against the status quo, like Bernie against Hillary, you're going to pay."

{::PAGEBREAK::}

Different colorsIn 1975, Alexander went back to India for a summer. He took along a troubled fifthgrader from Willow Run High School, where Alexander taught for five years.

Ira Harrison, now an Ann Arbor fire inspector with two kids of his own, said the trip changed his life.

"When someone else thinks you're so important that he'll take you halfway around the world, it leaves an impression," Harrison said.

He marvels that his parents allowed the trip at all.

"My father was good at reading people," Harrison said. "I'm not sure how I would react to a trip like that with my own kids, but he trusted Bob."

Early in the trip, Alexander pulled a sleepy Harrison out of bed to see the sun rise over the Indian Ocean. It's one of Harrison's most treasured memories.

"The sun came up out of the water, it was all these different colors and it was amazing. It sounds so simple, but it made me stop and think about things differently."

Alexander still considers Harrison family.

"We had a lot of discussions about life," Harrison said. In one heart-to-heart, Harrison told Alexander he hated his sister, with whom he was constantly fighting. "He told me hate is too strong a word to use on people," Harrison said. "Hate cancer or injustice, but not people."

Harrison choked back tears as he spoke.

"I was raised by him. I love Bob."

In the late 1970s, Alexander and Pollack taught a disco dance class together at Washtenaw Community College.

"He was wearing plaid pants and I know he had sideburns," she said.

Pollack was an early beneficiary of Alexander's political instincts.

In 1982, Alexander was a staffer for then-state Sen. Edward Pierce of Ann Arbor. When Pierce decided to run for governor, Alexander's time for public office finally seemed nigh. Pollack, then a member of the school board, would run his campaign.

The more Alexander thought about it, the more he realized Pollack was better known in the Senate district than he was. What is more, the Republican candidate was a woman, and a moderate, who might tempt Democratic votes away from Alexander.

Alexander opted out of the race. Pollack won and went on to a distinguished career in public service and environmentalism. She served as state senator from 1983 to 1994 and headed the Michigan Environmental Council from 1996 to 2008. In 2010, President Barack Obama appointed her to lead the U.S. section of the International Joint Commission, the body that resolves U.S.-Canadian disputes over water boundaries.

As state senator, Pollack's signature achievement was the "polluter pay" law requiring polluters to pay for environmental cleanup.

"I'm known as the author of the legislation in 1990," Pollack said. But the impetus, she said, came from Alexander.

"In my first week in the Senate, he told me I would be eaten up by day-to-day demands if I didn't carve out some major longterm goal and make time for it," Pollack said.

"It was Bob who had the vision to go for something large and important," Pollack said.

Alexander hit another sacrifice fly in 1995, when he bowed out of the race for East Lansing City Council. Although he earned a slot on the ballot by finishing sixth in the Democratic primary, he urged his supporters to vote for the progressive triumvirate of Sam Singh, Mark Meadows and Douglas Jester in the general election. The strategy worked. All three won and all three took a turn as East Lansing mayor.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Alexander led campaigns for dozens of fellow Democrats running for Ingham County Commission, East Lansing School Board, state representative and other offices. He headed the Michigan Draft Al Gore for President campaign in 2007 and was state campaign director for Dennis Kucinich's 1994 presidential run. The scroll of Bob's allies and causes is much too long to fully unroll, except perhaps in a dirigible hangar.

But when it came to running for office himself, Alexander was wary of wearing out his welcome with voters. In a 1995 letter to supporters explaining why he pulled out of the East Lansing city council race, he anticipated being attacked as "the Engler recall leader, a Zolton zealot, an ole HRPer, and from Ann Arbor!"

Many people saw his two runs for U.S. Congress as two more sacrifice flies. He doesn't see it that way.

He prefers to call his 2004 campaign "educational."

"You can't beat Mike Rogers with $80,000," he said.

But in 2008, Alexander thought he had "some cutting edge stuff " that could put him over the top. He warned of widespread plague from the rat's nest of collateralized debt obligations and other arcane Wall Street instruments that brought about the 2008 financial collapse. He identified $800 billion in unnecessary administrative and lobbying costs in the nation's health care system.

"It didn't get any attention from the mainstream press," Alexander said.

Rogers brushed him off with ease. When Alexander showed an uptick toward the end of the 2008 race, the Republican flooded the district with smiley TV spots and negative ads warning of "taxpayer giveaways to illegals." Alexander could only afford to rebut with a mailer. In Michigan, Democratic challengers got far less support from the party's national campaign committee than incumbents.

"[The Committee] is a club of the Democratic members of Congress and they don't let a lot of people in," Alexander said. "I was done running, for myself, for office."

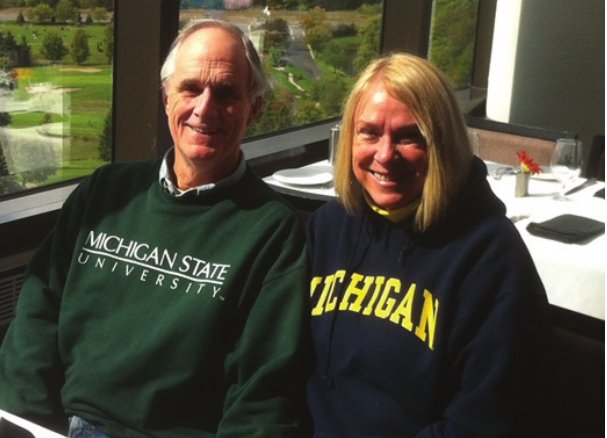

Yes AlexanderAs our talk last Friday afternoon wound down, Alexander got up from his chair to greet his wife of 15 years, Julie, a 44-year veteran in human services for the State of Michigan.

She was holding flowers from a retirement party her co-workers threw for her that day.

"It's a different chapter than I thought would come next, though," she said.

On Jan. 29, doctors found cancer in Bob Alexander's pancreas and liver. He began chemotherapy Feb. 24 and is enrolled in a clinical study at the University of Michigan hospital for a new drug he hopes will curb the growth of the cancer.

The illness hit him in the midst of a typical cascade of Bob Alexander projects. Alexander retired in 2002 after 30 years working for the state of Michigan, in the Department of Social Services and other departments, but he’s kept himself busy. His living room is still piled with charts analyzing state elections with precinct-by-precinct, Battle-of- Gettysburg precision. Since his 2008 defeat, he has devoted much of his time to finding ways to elect more Democratic state representatives in Michigan, homing in on 20 key races. The charts pin down precincts with “difference makers,” voters whose participation tips an election one way or the other.

Now he's busy researching cancer treatments on the Internet and charting his 21-day cycles of chemotherapy.

"I don't know what's going to happen to the [Democratic Party] progressive caucus, but it's going to be no longer my concern," he said quietly.

But there's a twist in the latest chapter of the Bobyssey. After working for Bernie Sanders' Michigan campaign, Alexander is more certain than ever that the palace gates are about to swing open for progressives in America.

In Mark Grebner's analysis, it's not so much the Democratic Party that's wheeling back around to Lighthouse Bob. It's the world.

"Socialism doesn't scare people," Grebner said. "The death penalty is dying out. Marijuana is gradually becoming legalized. Homosexuality has become not just routine, but almost boring. The world is talking about economic inequality. In some ways, the world is smiling upon Bob and his beliefs more than it did 10 or 20 years ago."

After decades of blank stares, rolling eyes and slammed doors, the old canvasser has never seen young people get so excited about politics.

Last September, Bob and Julie visited Alexander's daughter from his first marriage, Lindsay, in Thomas, W. Va., a tiny town near the headwaters of the Potomac River. Alexander and his first wife divorced in 1987.

The music, the politics and the scene had more than a whiff of 1960s Ann Arbor. Thomas, a former coal town in the Alleghenies, is becoming a lefty, hipster hub with a restaurant/venue called the Purple Fiddle.

Lindsay Alexander, 32, performs in a rock duo with drummer Chuck Richards under the name Yes Alexander. (It's her nickname from way back, Bob explained, because she's always up for a celebration.)

"The music — I can't do it justice," Alexander said excitedly. "It's really noisy and full of pathos, anguish and so on. My daughter's bouncing up and down while she's playing the keyboards and singing and Chuck is doing these fantastic rhythms."

True to form, Bob got antsy during his brief visit and helped locals organize a Bernie Sanders event.

"By 6 o'clock we had 48 people, in a town of 380," he said. "I spoke to 15 or 20 percent of the population!"

Julie's voice came from the next room.

"Are you drinking water?"

He dutifully took another sip.

"That's what I'll miss. Seeing the positives," Alexander said. "But we did what we could and I feel really good about it."

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here