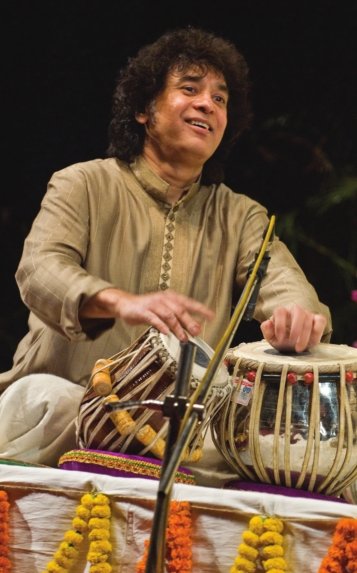

Hussain is one of the world’s most famous players of the tabla, the traditional pair of drums used in north Indian Hindustani music. Raised in India, Hussain arrived in San Francisco in the 1970s at the height of the Hippie Era. He cut his teeth on American music by jamming with the Grateful Dead and John McLaughlin.

Over the next 40 years, Hussian performed with everyone from cellist Yo-Yo Ma to rocker Van Morrison to banjo virtuoso Béla Fleck. He is a founding member of Planet Drum, an all-star percussion outfit led by Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, as well as electronic world music group Tabla Beat Science.

Hussain turned 65 earlier this month — “I’m officially a senior citizen,” he joked. “I’m eligible for Medicare and all that” — but he shows no signs of slowing down.

Hussain’s Masters of Percussion tour comes to the Wharton Center Tuesday. City Pulse caught up with the musician at his home in California as he was preparing for the tour.

Is it true that you started playing tabla at the age of 3?

In India, in those days, we were 40 years behind the times. When you had a son, the son had to be groomed to be in the father’s profession. And with my father being a drummer, as soon I was born, he would hold me in his arms and sing rhythms in my ears. He was trying to get all that information in my head, in my subconscious mind, so that I would be ready for it when the time came. By the time I was 3, I was already learning, mentally at least, the language of the drums, the grammar of it. By the time I put my hands on the tabla and was told what to do, the basic information was already there. So yes, I started early.

What is the Masters of Percussion tour?

It started in 1992 with my father and me doing a percussion tour of the United States and Canada. When we came back in ’94, we added my brothers. It became a family drumming tour. After that, my father said, “Why don’t you concentrate on showcasing the rarer drumming traditions of India?”

In India, we have about 200 different percussion instruments and about 20 different drumming traditions. There are masters of drumming in very remote corners of India that you seldom hear about. So his idea was to bring drummers who need some exposure and have them perform on the stage that they deserve. That’s how Masters of Percussion was born in 1996.

We would travel to the remote corners of India and look for drummers, and when we found someone, we would bring them to Bombay and interact with them and see if they had the temperament to interact with other drummers and if the sounds worked together. Once they are ready for performance, we initiate them into the Masters of Percussion tour. Over the years, there have been a couple hundred drummers we’ve worked with.

What kind of drummers are you bringing with you this year?

This year, I’ve concentrated on cylindrical drums — two-headed drums played on either side. I wanted to showcase different traditions of that. There’s Navin Sharma, a folk drummer coming from the central part of India. He plays the dholak, which is a two-headed drum used in the folk music of central India. Then there is Mannargudi Vasudevan, a thavil player. Thavil is an instrument from Kerala and other parts of south India that’s used to play in wedding processions, temple processions and stuff like that. Then there’s Anantha Krishnan, who plays the traditional drum of southern Indian classical music, the mridangam. I thought that when you put these three together, they have three different traditions to represent, three different styles of playing. Sonically, they are very different from each other, but we find a common path to make a rhythmic journey together.

Apart from that, we have a Sabir Khan playing sarangi, which is a bowed instrument. It will give us the melodic content of the regions these drums came from so that you can see how they interact with the songs and the melodies of the areas they represent. And I will be playing the north Indian classical tabla. Between us, we’re going to go on a rhythmic journey and give the audience sort of a bird’s eye view of Indian regions — their songs, their rhythms, their language.

This year is the 25th anniversary of “Planet Drum” —

Twenty-five years! Whoa!

Yes, it was released in 1996.

It was the first album to win a Grammy for world music — that was the year they introduced the category. We have the honor of receiving the very first one.

I just got a mail from Mickey on my birthday. He is rebuilding the studio where we recorded “Global Drum Project” and “Planet Drum” and other albums. So right after this tour is over, we’re going to go camp in there and see what we can bash out. The whole idea is to gather the Planet Drum alumni — the ones that are still around and in good health — and make another trip.

I have to credit Mickey with introducing me to the rhythmic world outside of India. I had not known of people like Babatunde Olatunji or Airto Moreira or Giovanni Hidalgo or Sikiru Adepoju … oh God, so many other percussionists I had not heard of. It was Mickey, in 1971, when we started working together, who started putting records in my hands. He’d say, “Check this out,” or, “Listen to the way this rhythm goes,” and so on. So I have to credit him with opening my mind, my eyes, my rhythmic world to the global experience that has shaped me into the drummer I am now.

You are known for Indian classical music, but you also co-founded Tabla Beat Science, a famous electronic world music group. How did that come about?

There was a time when people like Karsh Kale and Talvin Singh came up with this Asian underground style — drum and bass being the main ingredient. They started finding loops — loops of Indian instruments, African instruments and so on — and bringing those in to make a loop-oriented, rhythm-based style of music for people to dance to.

So one day I ran into Bill Laswell, and Bill said, “We’ve been doing this, and it’s great, but what if we did the same thing but bring in, on top of this, organic instruments. Real instruments.”

I went to Bill’s studio in Newark and we started putting some tracks together. We added Ustad Sultan Khan, the great sarangi player — he’s the father of the sarangi player who’s coming with me to East Lansing.

What was interesting with Tabla Beat Science is that you had Bill Laswell laying down that groove like only he can on the bass, the drum loops were being laid down by Karsh Kale, then, on top of that, all these organic tones were appearing — tabla and hand drums and sarangi — and it really came alive. It wasn’t robotic anymore.

That’s how Tabla Beat Science came about, and it really took hold in people’s imaginations. It became quite a successful group. We played concerts for 10,000 and 20,000 people, DVDs were made and it was a really great experience.

I just recently talked with Bill Laswell about doing the next installation of Tabla Beat Science. I have several projects coming up: the one with Mickey for the anniversary of “Planet Drum” and the one with Bill Laswell — 15 years of Tabla Beat Science.

How much longer do you hope to keep playing?

As long as there is stuff to learn. Most musicians want to learn more, want to grow as artists, want to expand their knowledge, their vision, their expressive quality. To do that, they need to interact with artists all over the world and learn different languages of music.

I find that being a student is a great thing, and as long as I keep being a student and as long as there are people willing to work with me and give me insight into their music, there is no reason to stop.

Music is not like sports, where after a certain time the body does not respond as well, and you have to become a coach or commentator or something. You can play music well into your 80s. Ravi Shankar played until he was 90, and my father played when he was 80 years old, so I don’t see any reason to stop. There’s miles to go before I sleep and a lot to learn in that time.

Zakir Hussain

With Masters of Percussion 7:30 p.m. Tuesday, April 5 Tickets start at $23/$15 students and youth 5-18 Wharton Center 750 E. Shaw Lane, East Lansing (517) 432-2000, whartoncenter.com

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here