The creator of 60 bold paintings now on display at the Wharton Center — available for viewing by appointment only — gave his age as “nothing.”

“I don’t like to put an age on things,” he explained.

Great, you might think, another smartass artist.

Not so fast.

“Dense,” “slow learner,” “retard” — Staib has been pigeonholed, pegged and pinned down all his life.

Thanks to his own persistence and shamefully late-in-life help, he went from a being a frustrated student, dreading the classroom, to a working artist, touring musician and award-winning Okemos Public Schools art teacher.

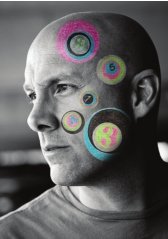

His lifelong struggle with dyslexia has left him with a well-earned stubborn streak. He’s wary of any word, any number, that could lock him in a category.

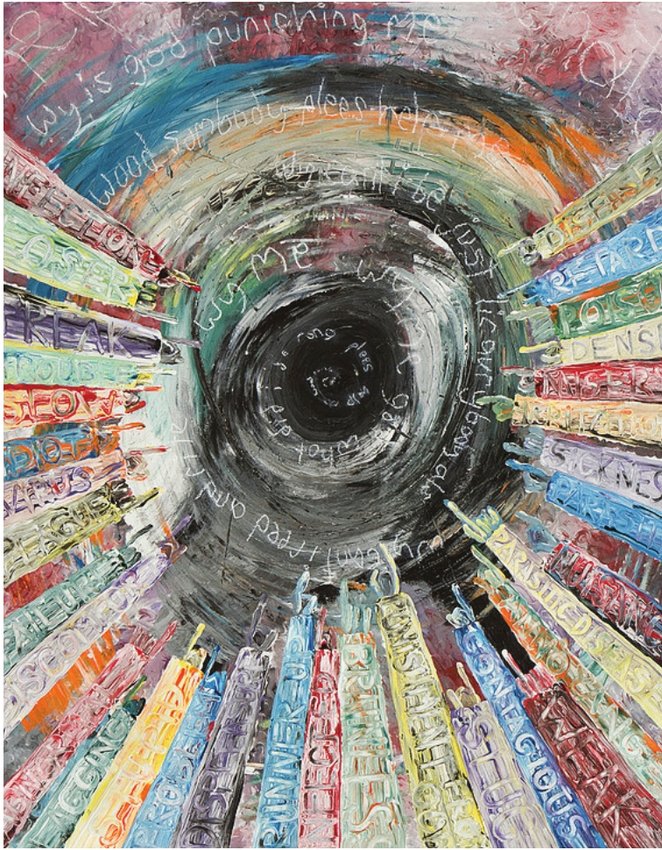

“Labeled,” the first painting Staib ever made and a highlight of the Wharton exhibition, makes the theme painfully explicit. After finally earning his undergraduate degree at Michigan State University, Staib poured all the frustration of his K-12 experience into a ply- wood panel 8 feet wide and 4 feet high.

He scrawled ghost-like phrases, such as “Wy me?” and “What did I do rong?,” in thin white letters and flushed them, swirling, into a black hole ringed by a rainbow of colors.

To soak his message into the work, he used rejected paint cans from Home Depot and other stores.

When he was done with the painting, he stood in front of it and cried.

“We’re so beat down by the system, we feel like failures,” Staib said.

The painting explodes with liberation. Staib was through hiding. He’d done enough of that in school.

Hanging with George

At the school library in rural Rome Center, Mich., where Staib grew up, he checked out the same picture books over and over.

“One of the last places I wanted to be was a library,” he recalled. “Nowadays it’s the opposite. I’m a bookworm.”

To write a book report, he picked books that were made into movies and based his report on the movie.

“I channeled the right side of my brain ever since I was little,” he said.

He dreaded having to decipher words and read them out loud.

“I tried to blend down and sink in my chair — ‘Please don’t call on me,’” he recalled. “Reading was so painful. I spent a lot of time crying.”

In the 11th grade, he was told he read at a “low elementary school level.” He graduated with a 1.6 GPA.

“It was crazy that I made it at all,” he said. “Music is what got me through.”

Music still fills his head, often in the form of vivid imagery, a sensation that sometimes goes with dyslexia.

“It drives me nuts,” he said. “I can literally see music notes, walk through them.”

He composes and arranges music in his head while mowing the lawn or walking his dog, a black lab named Bella, in tempo.

“There’s the drum part, the bass part and so on,” he said. “I put it together as I’m walking, memorize it and I’m ready to execute.”

Music was a lifeline for Staib from third grade, when he started organ lessons. When he heard a student musician take a drum solo at a high school music program, he was hooked. He tried out for fifth grade band and made it.

Staib’s jumpy energy reflects the soundtrack of his youth, ‘80s rock like Tears for Fears, Simple Minds, Duran Duran and a-ha. His first concert, as a kid, was Iron Maiden.

After graduating high school, he didn’t even think of going to college.

“No more reading and writing,” he said.

“I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life.”

Music came to the rescue. Staib badgered Motown drummer Aaron Purdie, who played in the ‘70s with soul legends James Brown and Al Green, for lessons.

Purdie gave Staib one lesson to prove himself.

“He took me on,” Staib said. “I busted my butt.”

Staib was chopping wood in the backyard one afternoon when he got a phone call from a booking agent asking him to do a session with Parliament-Funkadelic bandleader George Clinton. Before he knew it, Staib was a fixture at Clinton’s house and studio in Brooklyn, Mich., not far from Michigan International Speedway. They spent quality time together on Clinton’s living room couch watching “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” (Staib was a “Rocky Horror” virgin at the time.)

One day, Staib was sitting on the couch, doodling in a sketch pad Clinton kept around. Clinton walked in and asked Staib for help memorizing lines for his role in Prince’s 1990 film “Graffiti Bridge.” He tossed the script to Staib and asked him to feed Prince’s lines to him.

“Prince’s writing was on the script,” Staib said.

Staib still has a cassette, given to him by Clinton, labeled “George Clinton Prince Demo,” with the two icons jamming together.

‘Rodeo’ in the saddle

On a trip to California, Staib spent time hanging out with another of his heroes, legendary session musician and Toto drummer Jeff Porcaro. The music adventures were fun, but friends kept pressuring Staib to get a college degree.

He worried that his trouble with reading and writing would hold him back, but he visited Jackson Community College anyway. To his surprise, he walked out of a meeting with the dean of the Music Department with a two-year scholarship. He hoped he wouldn’t have to go through the reading and writing tortures of grade school.

“Music is all math, all fractions,” he said.

But at the end of his first semester, he walked into a test for a class in non-Western music and had to bite his tongue to keep from “freaking out.”

“It was an essay test — every question,” he said.

He hastily wrote a few sentences about his struggles, walked out of the room and cried in the hallway.

He trudged home in defeat, but soon got a call from the dean. He told Staib he was dyslexic and offered him help.

“For the first time in my life, there was a label for what I was,” he said. “I could research it and find out how I tick.”

From there, Staib was recruited to the MSU drumline, where his nickname was “Rodeo,” and ended up with a scholarship to the School of Music.

The college bronco almost threw him off — he spent some time on academic probation — but Staib learned to speak up about his dyslexia, get help and battle his way to graduation day.

An English professor taught him to use tools, such as color-coded note-taking, multicolored highlighting and Franklin spellers that help readers find the word they’re trying to spell out.

“Black print on white scrambles us in the head,” he said.

Despite his progress, he bombed exams in biology and horticulture.

“Latin names of plants? I can’t even pronounce them, let alone spell them,” he laughed.

Getting through an art history class, with its many styles and periods, was a nightmare. But when professors gave him oral exams, he did fine.

He even got 4.0s in two art classes — sculpture and construction fabrication — despite being the only student in the classes who was not an art major.

Along the way, he started substitute teaching in several area school districts. He was especially successful teaching special education classes, where he related well to students.

Professors recognized Staib’s energy, enthusiasm and charisma and encouraged him to become an art teacher, but he still found himself swimming upstream. He studied art education at Saginaw Valley State University,

interned in Midland and applied to several districts as an art teacher, to no avail. One principal told Staib his reading and writing skills wouldn’t do.

At another district, Staib thought he was in the running for a teaching job.

“I rocked the mock teaching and everything,” he said.

At final interview with the superintendent and human resources director, Staib had to slow down when answering non-art-related questions.

“It takes me a while to process things and it sometimes it looks like I’m clueless,” Staib said. “They walked out of the room without even shaking my hand.”

The universe and stuffWith so many doors closing in his face, Staib decided to go for broke. He stopped trying to “talk like the teachers talk” and walked into an interview in Okemos playing the role he should have played all along.

“I decided to be myself,” he said. “I basically took over the interview, showed them my private artwork, what I did with student teaching, what my goals are.”

When he got home, his wife was waiting for him with news that a call had already come offering him the job.

“I turned around, drove back to sign the papers and cried like a baby all the way,” he said. “They looked at me for my talents and not my weaknesses.”

Staib has come a long way from cowering in the classroom, dreading to be called on. In 2006, he was awarded the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s Power of Art award for educators. In 2012, he received a League Educator Apple Award from the Broadway League.

Staib’s current Wharton Center exhibit is one of many projects he’s done at MSU. In 2005, Staib and his third-grade classes created a gigantic mixed-media panorama of the known universe, now on display at the MSU Cyclotron.

“It’s a massive painting that looks like the universe and stuff,” he said.

The art is backed with hundreds of LED light, programmed so the display never repeats itself.

Staib and his Okemos art students first invaded the Wharton Center in 2009, creating art based on visiting Broadway shows for the “Eye for Broadway” project.

MSU communications Professor Steven McCornack devoted a chapter to Staib’s story in his textbook, “Reflect & Relate.”

Staib hears often from students with dyslexia, ADD and depression — and even former bullies who saw the light after hearing him tell his story.

“It’s deep stuff; it’s like therapy for me,” he said.

Nobody is perfect

Overcoming a disability sounds about as appealing as taking a third job. That’s not the way Staib frames his message. When he talks to his students, or to groups like the Michigan Dyslexia Institute, he flips the story and urges them to harness the “power of dyslexia.”

“We can daydream in such vivid detail — we can create the emotion that goes with it,” he said. “That’s why you see Orlando Bloom and other dyslexic actors make themselves cry.”

With thousands of undiagnosed people struggling in schools and languishing in prisons, that power is still largely untapped. But with greater understanding, that seems to be changing.

“Fortune 500 (companies) are hiring dyslexic and ADHD people because of their creativity,” Staib said. “They have systems to keep them organized and on task.”

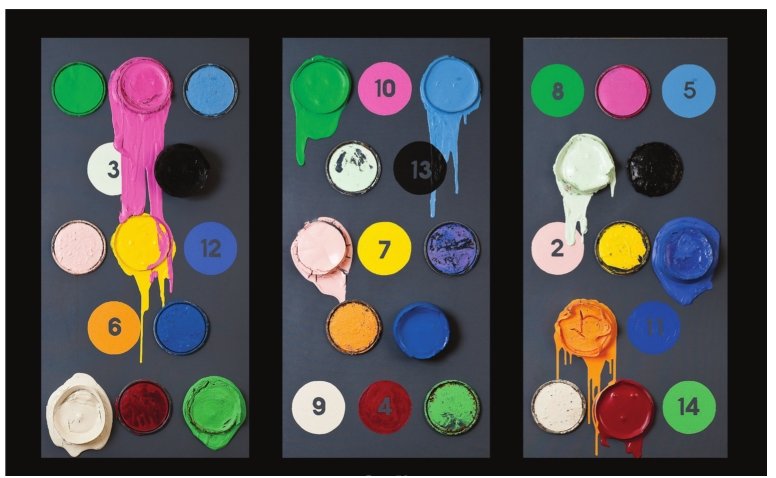

Staib’s meticulous method is a case in point. In his head, he assigns a number to every step in a work of art, from pencil outlines to white color fields to each color used.

“If number four is red, you can be sure I put that on fourth,” he said.

Numbers often float around in Staib’s paintings, as they do in his daydreams. In “Grey #1,” he juggles clean mathematics with drippy serendipity. He was inspired by prying open paint cans and observing the dripping crowns of paint crusting over on the lids. It took him a year, on and off, to nail them onto three plywood boards in the sequence and drip pattern he wanted.

“Isaac walking his pet dragon Lucas” is one of Staib’s favorite works. If Picasso weren’t such an arrogant jerk, this is the kind of playful image he might have come up with.

“I love the ‘60s and ‘70s feel to it,” Staib said.

The little guy with buck teeth in the lower right corner is named after Staib’s son, Isaac, and the dragon is named after one of Staib’s former students, who is also dyslexic. (A lot of people have asked to buy the painting, but Staib is saving it for Isaac.)

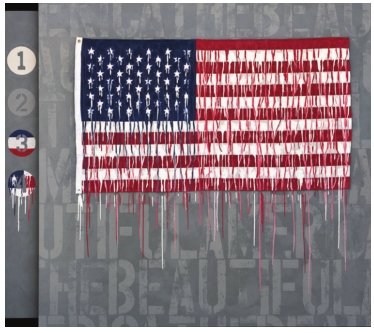

Staib manipulates symbols, forms and colors with a clarity and confidence that recalls Henri Matisse, one of his favorite artists. One of the most striking paintings at the Wharton Center exhibit, “These do,” moves into Jasper Johns territory, with a runny but gorgeous American flag on a field of the stenciled words “AMERICATHEBEAUTIFUL.” Staib said he was inspired by yard signs and bumper stickers saying “these colors don’t run,” but doesn’t want to prompt people on the painting’s message.

“I want the viewer to wake up and reflect,” he said.

When Staib is finished with a painting, he doesn’t let it sit around so he can come back to it and make changes.

“I keep it true,” he said. “I just do it.” While other people “ooh” and “aah” at museums, Staib scans each painting carefully for mistakes and corrections — any evidence of life and change.

“I like to get my nose literally in paintings, or look at it sideways,” he said. “Whether it’s Matisse, Picasso or whoever, I like to see their pencil marks, how they sketched things out or shifted something. That makes it more personal, like you’re getting into their heads.”

When Staib was a kid, he loved to take apart farm equipment and other stuff to see how it worked. It’s the same thing with artists, even the great masters.

“People think these great artists are perfect,” he said. “Nobody is perfect.”

Recently, Staib has moved toward cleaner, minimalist work with lots of solid colors.

“I simplify everything,” he said. “With all this technology, smartphones and computers, everything is so busy. It makes my dyslexic head numb. Wouldn’t it be nice to look at something that’s so simple, and you can just relax?”

“Simple” doesn’t necessarily mean smaller. Staib has plans to make even bigger paintings than the works on display in the Wharton Center.

“We’re talking 12 by 12 feet,” he said.

“I’ve got big recycled sheets of paper. I know exactly how the border will be reinforced, so you can tack them on the wall. It might be graphite or massive watercolor or acrylic — who knows? But it’s big stuff.”

“Inner-Self”

Eric Staib solo art exhibition Through Sept. 11 FREE (viewing by appointment only)

Contact Nina Silbergleit: nina@whartoncenter.com, (517) 884-3119 Wharton Center Grand Foyer and Stoddard Lounge 750 E. Shaw Lane, East Lansing

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here