Last month, George Howard went into the recording studio for the first time in his life.

So what? A lot of saxophone players make a lot of records — maybe too many. Why care about this one?

Be patient, keep your ears open and we’ll get there. That’s Howard’s approach to life. He will turn 92 on Feb. 22.

Born and raised in the segregated Deep South, a veteran of World War II, witness to the heyday of jazz in 1950s New York, Howard has been a quiet mainstay of Lansing music for decades, jamming around town and busking on the streets.

If you’ve worked downtown in recent years, you may have tossed a few bucks into his saxophone case on your lunch hour and walked back to your cubicle with “Blue Skies” in your head. Or if you were down and out, he might have thrown you some of his day’s takings, no questions asked. That’s the kind of gentleman he is.

Loved and respected by his many local friends and fellow musicians, Howard can be reproached for only one thing.

He’s been been holding out on us.

Wavelength of midnight

Last year, a nonagenarian with a sharp eye and an appreciative ear started showing up at Moriarty’s Pub downtown. Jazz Tuesdays has become a hothouse where local artists, MSU students and world-renowned jazz professors like Rodney Whitaker and Etienne Charles play for a jammed room every week.

Plenty of aspirants, from greenhorn students to retired duffers, approach drummer Jeff Shoup, organizer of Jazz Tuesdays, to ask if they can sit in with the band.

For a change, it was Shoup who had to coax the reluctant Howard to bring his horn.

“I didn’t want to get up there with all those bad cats from MSU,” Howard said last Wednesday. He was in a reflective mood, sitting in the living room of his friend, Laurence Max, popping grapes and ignoring the bottle of beer next to him.

“You see, I’m not what you would call a Sonny Rollins or a Charlie Parker, with the fast stuff,” he said.

Howard has no formal training, just big ears and a deep love of the music.

“I don’t sound like the rest of the people, because I’m just playing me, how I feel about the songs that I’m playing,” he said.

Shoup hears an endless supply of MSU hotshots, but he felt something special in Howard’s sound — the rich grain of experience, ribbed with 90 rings of life. They played together once at a gig in Old Town, and Shoup never forgot that sound.

Over the decades, Howard has cultivated a tone as smooth as 18-year Scotch, gentle as a mother’s kiss, sharp as your grandpa’s fedora and dark as katalox, the royal ebony wood of Mexico — the wavelength of midnight, with a hint of purple.

A few years ago, when Shoup was working at a day job downtown, Howard was busking in front of a burrito place on Washington Square.

“I’d go for lunch and hear this sound coming from down the block,” he said. “You don’t just pick up an instrument and have a sound like that.”

Finally, one night last spring, Howard got up his nerve and brought his horn to Moriarty’s. Shoup made sure the best players, including organist Jim Alfredson and guitarist Larry Barris, were up on stage.

“I knew everybody that heard him was going to be blown away,” Shoup said. “Sure enough, he played his head off.”

As the set wound down, Shoup shot a meaningful look to his bandmates. That sound had to be documented.

Just three weeks later, they were in Alfredson’s home studio on the west side of Lansing.

The CD begins with Howard playing all by himself, sauntering into the first tune, “Bye Bye Blackbird,” like a man quietly opening a door.

“He didn’t count in or do anything,” Alfredson recalled. “I’m like, ‘OK, I guess we’re going.’”

Shoup expected to record for at least two days, owing to Howard’s inexperience in the studio. They were done in two hours. But those two hours were 90 years in the making.

The ‘black soldati’

A thing called George happened to Howard’s mother Feb. 22, 1925. She was about to go to Alabama State University, having graduated from industrial trade school, when she met some friends who were a little older and “a little fast,” in Howard’s words.

“They went on this hayride, and that’s where I was made,” Howard said, laughing.

He grew up in Birmingham to the sound of jazz, blues and gospel music.

“We had the good stuff,” he said, “Duke Ellington, Woody Herman, all the big bands.”

He walked past a well-equipped all-white school every day to get to a ramshackle school for black kids.

“They had a nice bus,” he said. “They used to pass us in the wintertime, throwing spitballs and stuff.”

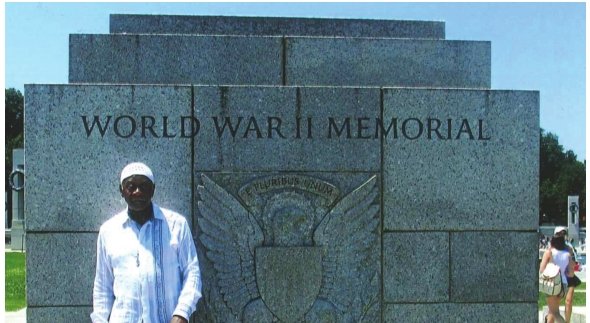

He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and stationed in Italy, near Naples, in an all-black unit. He remembered seeing old people and children scrounging for scraps in the garbage and giving them his rations.

“Those people loved us,” he said. “They called us ‘the black soldati.’”

On duty in Corsica, he got homesick for buttermilk and cinnamon rolls. A baker gave him two dozen rolls.

“No pay, no pay,” the baker said, waving him off. While Howard was on leave in Switzerland, a jeweler gave him a Swiss-made Richard watch and a bottle of French perfume.

A couple sitting next to him at the movies invited him to spend a day at their castle.

“They had every doggone album Duke Ellington ever made and all that stuff,” Howard said. “It was beautiful, man. They treated us like royalty.”

Segregated Birmingham was tough to take after that.

“When I got back to America, the same stuff was going on,” he said. “After all the hell I went through overseas, I wasn’t going back here and stay in a place like that. So I moved to New York.”

Orbicularis oris

Howard arrived at Penn Station in 1947 with $5 in his pocket. He landed a job at a laundry the next day. Soon after that, a school friend who worked at New York Hospital got him a job as an orderly.

Howard liked anatomy in high school and had a knack for it. His boss, a brain surgeon, overheard him chatting with a medical student one day.

“We were talking about the orbicularis oris (the muscles around the lips) and all that,” Howard said, savoring the Latin. He didn’t know it yet, but his own orbicularis oris would soon play a crucial role in his life.

Dr. Stanley made Howard his operating room technician, with a raise in pay.

At night, Howard made his way to the legendary Savoy Ballroom or headed to one the most fabled stretches of concrete in jazz history, 52nd Street, home of Birdland, the Bandbox, the Onyx, the Three Deuces, Minton’s Playhouse — birthplace of bebop — and many other clubs.

“I got poisoned by the saxophone players,” he said. “Sonny Rollins, Stan Getz, all those guys.”

Howard got to know Duke Ellington and his band on a first-name basis.

“Those guys were so beautiful,” he said. “They were just so enthralled over the fact that you liked their music.”

Among Ellington’s men was Howard’s saxophone idol, the sinuous and insinuating Johnny Hodges.

“That’s why I wanted to play the alto — oh God, Johnny Hodges,” Howard sighed.

Busy with work by day and dancing and “meeting the ladies” by night, Howard didn’t think of picking up a horn. He married Cora Smith, a woman he met at the Savoy, moved to Newark in 1959 and signed up with an employment agency. With a wife and three kids, he ended up working in the men’s room at a country club, shining shoes to make extra money.

A customer kept on raving about a town called Lansing, Michigan, “where people are nice, and you can raise your kids.”

But Howard didn’t like Lansing at first.

“It was too corny,” he recalled. “When we came through downtown on Washington Avenue on the bus, I said, ‘What the hell is this cow town?’”

A job opening for manager at the Lansing YMCA was hard to resist. He later took a job as a physical therapy technician at Ingham Regional Medical Center.

Jazz in Lansing was sparse, but on weekends, Howard took the bus to Detroit, where jazz greats were playing by the dozens.

“Man, that was it,” he said.

Still in the thrall of alto man Johnny Hodges, Howard went to a second-hand store and bought a $69 silver alto saxophone that wouldn’t stay in tune.

“My wife and kids would say, ‘Oh my God, put that thing away,’” he said.

He soaked it in the bathtub to make the pads swell up and force it back into tune.

Exiled from home, he practiced in the basement of a friend who ran a barbershop. He took informal lessons with Keith Barto, a veteran big band player who lived in Okemos.

The barber started to like what he was hearing in his basement and tipped off local bandleader Earl White, who led a quasi-funk band called Earl White and the Motiques. White showed up at the barbershop one day and told Howard, “Get your horn, we’re going to Chicago.”

“You’re crazy,” Howard told him.

“I said get your horn.”

White turned out to be a crook, skimming off the gig money for himself, but playing for the public was a rush for Howard.

“Man, that was a hall,” Howard said. “To me, it looked like 10,000 people out there, even though it wasn’t that many.”

‘Oh yeah, George’

The saxophone “poison” surged into Howard’s veins, with no antidote in sight. He traded his alto in for a tenor, paying an extra $450 for a new Selmer Mark VI.

In Detroit, he hooked up with a group of players from MSU who played Thursday nights at a club called Bomac’s, on Gratiot Avenue near Broadway Street. They teased him about his lack of training.

“Here comes George from Lansing,” the organ player would say. “Let’s see if he makes it through a tune.”

One week, Howard heard a raspy voice behind him say, “Don’t let these guys bug you.” It was Marcus Belgrave, the great Detroit trumpet player.

“You sound good,” he told Howard.

“Some nights I was good, some nights I wasn’t,” Howard said.

One night, playing the standard “Blue Moon,” he inserted the melody from the show tune “Some Enchanted Evening” so deftly that a musician in the audience took notice and came up to him after the tune to shake his hand.

“My head got a little bit bigger,” Howard laughed.

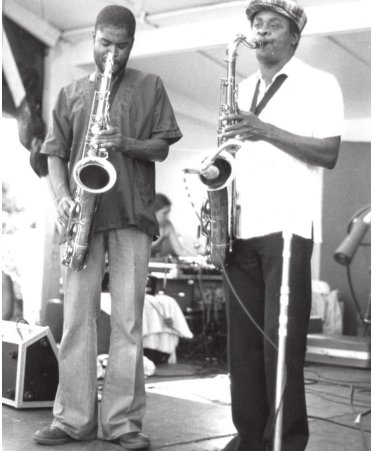

Back in Lansing, Howard became acquainted with Roscoe Mitchell, a legendary figure in Chicago avant-garde jazz, who lived in Bath, north of Lansing, in the early 1970s. Mitchell co-founded two of the most important avant-garde ensembles in jazz history, the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians.

“The man is a genius,” Howard said. “I learned a lot from him. A lot of people tell me I have a great tone. I got that from Roscoe.”

In the 1980s, Howard fell into a long-running gig at Jambalaya’s on Round Lake Road with singer Panthea Hawes. It worked well, but Hawes annoyed Howard with her habit of interrupting solos.

“She’d get happy,” Howard said. Tossing aside his plate of grapes, he jumped out of his chair to re-enact the scene.

“I got into it and got wound up in my solo, she’d cut you off: ‘Oh yeah! Yeah! Oh yeah, George! Yeah, yeah, yeah, play it again!’ I wasn’t going to play it again,” he cried, cracking up. “I wanted to move on. I’d say to myself, ‘Oh, Jesus.’”

One night in the 1980s, he sauntered into Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit carrying a red saxophone, wearing a Russian fur hat and long, beautiful coat.

He jumped from his chair again to imitate his younger self, strutting across the room with a big grin on his face.

“People stopped talking and whispered ‘Who is that?’” he recalled. “I lied to them. I told them, ‘I’m just back from a gig, I thought I’d check y’all out.’ I didn’t have no gig.” He laughed.

“I looked pretty good that night. I played the devil with ‘em. I asked some ladies if I could sit down and join them. They said, ‘Oh, yes.’” He laughed again.

After Howard retired in 1989, he spent a lot of his extra time practicing his horn, with encouragement from former MSU jazz professors Wessell “Warmdaddy” Anderson and free lessons from trumpeter Derrick Gardner. He married his second wife, Anne Paquet, in 1994 and they are still going strong.

In the early 2000s, Howard played at East Lansing’s Green River Café and busked on the sidewalk outside. When the place closed, he busked outside New York Burrito on Washington Square in downtown Lansing for about three years for free food and tips from passersby. “I loved it,” he said.

Scoot, scat and squawk

Terry Terry met Howard more than 30 years ago at an informal weekly gathering of musicians and artists hosted by MSU art professor Bob Weil and his wife, Judy.

Terry, now Lansing JazzFest director, had just returned from Guatemala and was sporting a beautiful shirt he bought there.

“The first thing Howard ever said to me is that he liked the shirt — and could he have it,” Terry said with a laugh. Terry gave it to him and went home in his undershirt that night. They’ve been friends ever since.

“A lot of people love George,” Terry said. Howard has jammed for years as part of the OtherBand, a rotating group of like-minded artist-musicians including Terry, saxman Jack Bergeron and guitarist/bassist Dennis Preston.

“I play some grooves on bass for him and Jack to just scoot, scat and squawk on top of,” Preston said. “I really like jamming with George. I'll get a run going, and he lets loose on it. I just close my eyes and grin while I'm listening to him. His playing amazes me.”

The jams take place mostly at Terry’s house, in the spirit of the old Weil salons. The music is all improvised.

“Some artists just want to make art, they don’t really care about the business part,” Terry said. “Those are the ones I’d rather hang out with.”

That’s not all

Nobody but George Howard can be George Howard, but people still ask him how he’s managed to thrive into his 90s. He doesn’t smoke, eats good food, exercises and is “very moderate on the booze.” But the master key to being George is clear to anyone with ears.

“Music is like loving God to me,” Howard said. “Any good music. I don’t care if it’s classical, hillbilly — if it’s good, I can dig it.”

People often ask him to name his favorite jazz saxophonist.

“All of ‘em,” Howard said. “They all have their own thing they want to say.”

Jim Alfredson, one-third of the chart-topping ensemble Organissimo, has played with dozens of jazz greats and toured the world with singer Janiva Magness, but playing with “George from Lansing” on the new CD was a unique experience for him.

“I feel like I’ve played with a direct link to the era of Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins, which is really rare now,” Alfredson said. “He’s kind of the last of a breed of men.”

At the Dec. 13 recording session, Alfredson found himself checking his own tendencies to “showboat.”

“I was hearing his approach, and it affected my playing,” Alfredson said. “Take a breath, take your time and you’ll get there when you get there.”

The standards on the CD all have a special meaning to Howard. Although there are no vocals on the disc, he keeps the lyrics in mind when he plays.

“I heard this stuff all my life,” he said. “I listened to the big bands, Glen Gray and the Casa Loma Orchestra, Patti Page, Doris Day. All those songs are embedded in me, in my consciousness.”

Howard’s take on “I’m an Old Cowhand” is a sly delight. (It’s not an old cowboy song, by the way, with lines like “I know every trail in the Lone Star State/’cause I ride the range in a Ford V8.”)

And Howard’s orbicularis oris produces a particular eloquence on the simple, understated 1952 standard “That’s All.”

“It reminds me of my courting days, when I had this beautiful lady that I liked,” he recalled with extra warmth in his voice. “‘The love that I can only give you, that’s all’ and stuff like that. Now, that tune brought tears to my eyes. I think that’s the best tune on the CD, because it really got into my soul.”

He shook his head wistfully, half singing, “That’s all.”

Although a second CD isn’t out of the question.

“Maybe, possibly, if this one goes OK,” he said.

George Howard “How It’s Done” CD release party 7 p.m. Tuesday, Feb. 28 FREE Moriarty’s Pub 802 E. Michigan Ave. (517) 485-5287, moriartyspublansing. com

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here