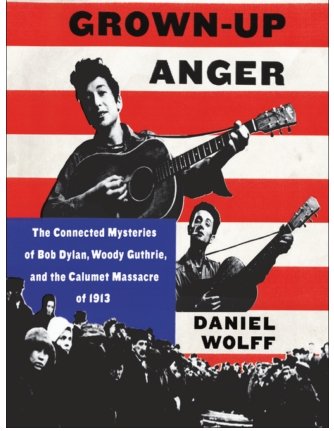

Author, poet and documentary film maker Daniel Wolff has taken on a daunting, Herculean and sometimes dangerous task with his newest book “Grown-Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913.”

Cleaning up the “Augean stables” surrounding the Dylan-Guthrie myth is hard enough, but add in the Calumet Massacre and you need an almost mythical hero to dig out from the deep piles which Wolff attempts to do in his new 354- page book, including 70 pages of notes and bibliographic references. Wolff has already written highly acclaimed books on Springsteen (“4th of July, Asbury Park: A History of the Promised Land”) and Sam Cooke (“You Send Me: The Life and Times of Sam Cooke,”) both tremendously conflicted songwriters and performers, so it is a task he is familiar with.

Enough books have been written about Dylan to fill a small library and although there is a lesser number written on Dylan’s professed muse, Woody Guthrie, there is enough there to mine his life and compare the two folk-slinging giants.

Until recently, there was only Mother Bloor’s book, folklore, a historic marker and Woody Guthrie’s song “1913 Massacre” released in 1941, which helped us understand the Calumet Massacre and the tragedy’s imposing influence on American labor history. Steve Lehto’s Michigan Notable Book “Death’s Door: The Truth Behind the Italian Hall Disaster and the Strike of 1913” is cited as a source in the author’s notes along with a recent film, “Red Metal: The Copper Country Strike of 1913,” which was shown on PBS.

Speaking with Wolff in a phone conversation from his home in Nyack, New York, he said, “It (Calumet) is a tough story and its aftermath is hard too.”

Wolff said he became fascinated with the topic as an angry young teenager (thus the title) after hearing “Like a Rolling Stone,” and thinking that the music of Dylan “would validate that anger.”

“In my book, I was trying to show that there is a line of anger that goes back and goes forward. Whether it was the various Red Scares, the anti-war movement, or Occupy (Wall Street) or Black Lives Matter there is a century of resistance,” Wolff said. He also sees that anger played out in the songs of hip-hop singers.

He explores this line of anger through the music of both Guthrie and Dylan and the mysteries surrounding their lives.

He first details how Dylan comes to meet Guthrie. In essence, a death-bed’s pilgrimage to where Guthrie is dying of Huntington’s Chorea. As legend has it, Dylan, who bummed across America like Guthrie, dressed like Guthrie and even held his cigarette like Guthrie, played Guthrie’s own songs back to him in the hospital. It’s hard to imagine what Guthrie thought of this: was it self-indulgent or pure adoration?

That may have been answered a short time later when Dylan’s first album includes the original “Song for Woody” as a tribute to the legend and arguably Dylan’s inspiration. It’s in Dylan’s lyrics that he perhaps tells the whole truth: “The very last thing that I’d want to do is to say I’ve been hitting some hard travelling too.”

Wolff documents how Guthrie and Dylan at various times obscured or flat-out made up things that created a mystery about their pasts.

“For too long we’ve looked at Guthrie as a Johnny Appleseed character,” he said.

Wolff however writes how during the multiple red scares Guthrie kept his Communist association’s “hush hush.”

The book points out that in many ways Dylan was similar.

“Dylan deliberately kept himself a mystery,” Wolff said.

As he writes about the two song writers and relates some of the purported details of their lives, Wolff use the single word “Maybe” to let the reader know that they are entering a grey area between truth and just made up details.

Lovers of music will be entranced by the name dropping and relationships Wolff pursues in his book. A reader will come away with the feeling of just how much the past influences songwriters, Dylan used the tune from Woody’s “1913 Massacre” for his “Song to Woody,” while Guthrie borrowed the tale and some of the lyrics from socialist and labor activist, Mother Bloor and her 1940 book “We Are Many.” Wolff also notes that folk singers often borrowed melodies and even lyrics, subtly changed, from the work of their predecessors.

Much of that was a practical approach to get people to sing along, by using easily recalled melodies in a time before recording devices and radio.

At the end of his book, Wolff makes a two-day visit to Calumet, something few Michiganders have done due to the inaccessibility of the area.

There he details the continuing mystery of the massacre (was it murder?) and how Guthrie came to write the sparse, haunting lyrics that would tie another music legend to the tragedy nearly 50 years later.

Guthrie, who only visited Calumet through the eyes of others, never considered the tragedy a mystery. A famous photo of Guthrie with his guitar tells the truth Wolff has been looking for all along. There, hand-written on the guitar, is the message “This machine kills fascists.”

Read this book twice; once for fun and then again to take in the incredible detail.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here