Summer of memoriesA look at Michigan in the summer of ‘67

Summer of memoriesA look at Michigan in the summer of ‘67 It was June 1970 and I was standing at the corner of Haight-Ashbury, the epicenter of the Summer of Love. But I had missed my chance in 1967. Instead of making my way to San Francisco, I had opted to make parts for steering wheels in Saginaw, Michigan.

Still curious to learn what I had missed all those years ago, I wanted to see if the Summer of Love was as magical as it was portrayed or if it was the result of marketing. In reality, it was both.

In January 1967, a gathering in nearby Golden Gate Park called the Human Be-In seemed to catapult the movement into the mainstream.

Charles Perry, a writer for Rolling Stone and author of what may the definitive book on the Haight-Ashbury scene, “Haight- Ashbury: A History,” wrote, “Life in the Haight had the exaltation of a play.”

“For some time the Haight had been shaped by events that came from all sorts of surprising quarters,” he wrote.

Swirling in the heady mix were radio stations, light shows, underground newspapers, head shops, poster artists and designer drugs — especially LSD — that were still legal and readily available.

Overlaying the high rent in Venice Beach was the down-on-its-luck nearby neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury. Its vast Victorian mansions had been saved from the 1906 San Francisco fire, and the area along the famed intersection became very attractive. For $20 you could rent a room which came furnished with a lifestyle.

Bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and the Holding Company would take over entire mansions, making them their headquarters and designated jamming palaces.

Haight-Ashbury, nestled near San Francisco Bay, in actuality was only a few short blocks long, but it featured unique attractions. It had a coffee shop, a seminal head shop and stores with unique names like “Far Fetched Foods,” “Mnasidika” and the “Blushing Peony.”

But most of all it was fun. It was where hippies could dress up and be free, where they could, as Timothy Leary urged at the Human Be-In, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.”

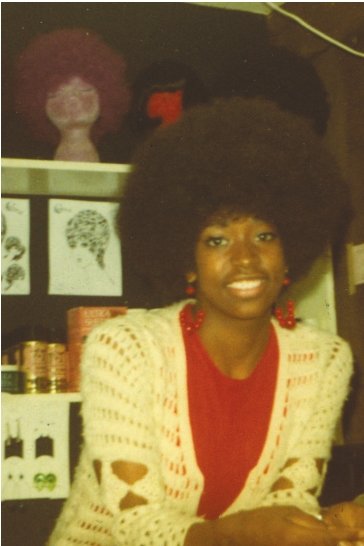

Here are five Michigan-related Summer of Love stories, from people who ventured out west during that time or brought a little piece of the Summer of Love back home.

Michael Erlewine

Magic was in the air in the summer of 1967, even in Michigan. Michael Erlewine and his Ann Arbor band, the Prime Movers, packed their 1966 Dodge to the gills with equipment and left for San Francisco in early June of that year. Erlewine was one of the more than 100,000 who poured into the city that summer.

Erlewine said that “you had to be part of it,” even though in 1967 “the bloom was a little off the rose.”

Even before his foray into the Summer of Love, Erlewine had some expertise in hippie culture. He dropped out of high school in 1960, hitchhiked to California and became part of the “beat generation.” He ended up living in Venice Beach and later in the Berkeley area, where in 1964 he took acid for the first time. He also tells stories of hitchhiking with Bob Dylan from folk gig to folk gig.

When they arrived in the city in ’67, the Prime Movers hooked up with guitarist Michael Bloomfield and played gigs all over the San Francisco area. For cash, they played at a variety of venues from restaurants to clubs like the Matrix. The group even opened for Cream at the Fillmore Auditorium, the first time they played in San Francisco.

While there, Erlewine would become attracted to the colorful posters promoting the major rock clubs like the Avalon Ballroom and Longshoreman’s Hall. Later, he would become a major collector amassing thousands of the posters by Chet Helms, Rick Griffin and others.

Much later he would build a camera to digitize more than 33,000 posters of the era and provide copies to the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library.

“We were in the scene and tried to survive. All we did was hang out,” Erlewine said.

Russ Gibb

Just before the Summer of Love fantasy, Russ Gibb, a Detroit area teacher and disc jockey, would make a foray to San Francisco to meet up with the owner and promoter of the Fillmore Auditorium, Bill Graham. Graham’s venue hosted thousands of hippies on weekends, where they would listen to music, dance, get high and become entranced by the phantasmagoric light shows.

Gibbs, an early adopter, brought the entire psychedelic ballroom concept back to Detroit. In 1966, he took his own stab at operating a venue with the opening of the Grande Ballroom. It would be that downat-the-heels dance hall where he’d host hippie legends like the Who, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, Cream and more.

As bands made their way east, they would bring with them the California lifestyle “look,” long hair and bellbottoms soon became fashionable across the country. Dance halls like the Grande, and, later, Grandmothers and the Stables in East Lansing, would become a window into this burgeoning lifestyle.

Although some still believe that the Summer of Love appeared fully actualized, it certainly was no modern-day “Pirates of Penzance.” It had deep roots, drawing from both the beat and surf cultures. By the summer of ’67 it had morphed into an amalgam of music, drugs, mind-altering experiences, free sex and freedom of thought. This blend was created by the combined experiences of key figures in, and leading up to, the Summer of Love like Jack Kerouac, the Merry Pranksters, the Diggers, Hells Angels, and the Family Dog commune.

Fulton Jay Hanson, Doug Maahs, Tom Cathay and Dennis Preston.

The feel and look of the Haight-Ashbury area would soon be replicated across the country in Chicago’s Piper’s Alley, Underground Atlanta and, closer to home, Plum Street in Detroit.

Lansing would take another tack called Free Spirit. In the old Home Dairy building in the 300 block of Washington Avenue, a group of entrepreneurs would fashion an indoor version of the Haight-Ashbury retail area with head shops, a record store, a pet store and about anything else folks wanted to try.

Two men from Madison, Wisconsin, saw an opportunity there. They were Fulton Jay Hanson and Doug Maahs, who arrived soon after its creation and, by early spring of 1969, refurbished the former downtown eatery and grocery store into a type of business that had never been seen before.

“Nobody had conceived doing it under one roof. It was totally out of the ordinary, especially for that community,” said Maahs, who now designs and builds kitchens for a living in Santa Fe.

Maahs remembers the creativity of the people who sublet the shops.

“They loved doing business, but just not in the corporate way,” he said. “At the time, everything seemed more-brighter more-intense. The vibe was very young, hip, friendly and stoned.”

That didn’t seem to bother the Wall Street Journal when it sent two reporters to Lansing to write about the hippie shop, publishing a front-page story about the new way of doing business.

Jay Hanson, who was seen as the driving force behind the concept, said, “The story of Free Spirit could be a movie.”

“It was a life-changing experience and we had people from all over the country coming in to see how we did it. We weren’t interested in Berkeley. In our mind, we were the epicenter of the world,” Hanson said.

One of the local entrepreneurs, then 19-year-old Tom Cathay, set up a record store in Free Spirit called Sounds and Diversions. He said he borrowed money from a friend to set up the store after working in the warehouse at Marshall Music Co.

The record store was located in the back of Free Spirit, but Cathay said they played music that went throughout the building.

“It became the soundtrack for the store,” he said.

He still remembers the first album he sold, CSNY’s “Déjà vu.”

But as quickly as the two Wisconsin entrepreneurs had blown into town, they vanished.

“One day,” Hanson said, “A chick came in and we got in a van and drove away.”

Cathay said he moved sounds out before Free Spirit closed in March 1975, to become what is now the New Daily Bagel. He also opened a stand-alone waterbed store called The Sleep Shop.

Glenn Brown

Glenn Brown is a local music producer who has worked with the likes of Eminem. His high school band added hard-driving electric beats and synthesizers to the mix. Hardly a band worth its salt would be without the Gibson Maestro fuzz pedal, commonly called the “fuzz box.”

Brown said music “became much more psychedelic” back then, particularly with the introduction of drugs.

Many bands also took up some of the antics of the Who and Jimi Hendrix, who at Monterey had their acts climax with the destruction of their instruments.

Music, art and lifestyle changes were not the only cultural characteristics which gave in to the wave of the famed West Coast summer.

Radio waves also underwent dramatic transformation, adopting some of the West Coast pirate or underground radio styles. For the first time, entire albums were being played without interruption. AM radio was pushed into the background.

John Sinclair

Advertising in all forms began taking on a sixties vibe with words like “groovy” and “blast” being used to describe consumer products.

One of the most astute and involved observers of the 1960s and author of “Guitar Army,” John Sinclair, believes the tenets of the flower power generation were subverted “by a lot of cornballs.”

He goes back to the Monterey Festival calling “San Francisco” a “corny song.”

“Advertising people took a beautiful thing and kicked it. The ideal is lost and we are just consumer ants,” Sinclair said.

Sinclair has seen a lot of sixties culture wash over his dam. He became the face of marijuana in the movement, when he was arrested and imprisoned for selling two joints to an undercover agent in 1969. He was later freed by the Michigan Supreme Court, after a dramatic “John Sinclair Freedom Rally” concert in Ann Arbor that included an appearance by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Sinclair was a founder of the annual Hash Bash in Ann Arbor and at one time was the manager of the MC5.

He said by the time the Summer of Love was underway, there already was a vibrant Detroit hippie scene.

“The best things to come out of the sixties were LSD, radio and the internet,” he said.

Sinclair’s lament that the Summer of Love was half hype is backed up by a former rock critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, Joel Selvin. Selvin wrote this about the Summer of Love in his book “Summer of Love.” “The Summer of Love never really happened. “Invented by the fevered imaginations of writers for weekly news magazines, the phrase entered the public vocabulary with the impact of a sledgehammer.”

For me, the end of the ‘60s and the extended Summer of Love came along in 1970, when I got a job as a security guard at the Goose Lake International Music Festival and was put in charge of a Detroit motorcycle gang there to provide muscle.

There weren’t many hippies there wearing flowers in their hair; they had been replaced by entrepreneurs selling everything from watermelon to laughing gas.

The best of the Summer of Love was in the rearview mirror.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here