Former tutor describes his life with Motown icon

Former tutor describes his life with Motown icon Stevie Wonder played on the world’s biggest stages and became one of Motown’s biggest stars, but in 1964 he did a favor for his tutor, Ted Hull, and played in the tiny gym at Marble School in East Lansing. Hull, who was Wonder’s tutor and constant companion during the star’s teen years, did his student teaching at the school under Virginia Collins.

Hull vividly recalls the day he got “the call” in September 1963 from Esther Gordy Edwards, the sister of Berry Gordy and Motown vice president. She wanted to hire Hull as a tutor for Wonder.

Wonder had already embarked on a remarkable career, but the lack of a proper education would have been a serious obstacle in his future life. It was Hull’s job to see that didn’t happen and for six years, until Wonder’s graduation from high school at the Michigan School for the Blind, he was by his side, as an employee of Motown.

Hull was 25 in 1964 and had recently graduated from Michigan State University. He was also an alumnus of the School for the Blind, graduating in 1957. When Wonder was first introduced to Hull, the first question he had was “Are you blind too?” Although Hull was totally blind in his left eye and had only 20 percent vision in the right, he had already spent two summers traveling the world solo.

Over the next several years Hull would find himself rubbing shoulders with the greats of Motown, including Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross and Martha Reeves, riding with them in a bus to events — and sometimes helping push it to get it started.

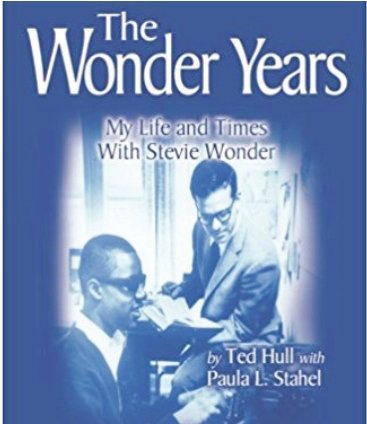

Hull wrote about these experiences in a self-published book, “The Wonder Years,” which first came out in 2000 and is still available on Amazon.com. It’s mostly complimentary of the Motown machine and its stars, but it does reveal some of their warts and quirks.

Hull is a good storyteller, and he’s at his best when he writes about the times he and Wonder were inseparable, flying across the world to various gigs in Japan, England and domestic venues big and small.

Hull writes with respect about blindness, but he is not above self-deprecation, telling some funny stories about the adventures he and Wonder had during his tenure.

On a visit to the Statue of Liberty, the two went up the down staircase and found themselves crushed against the wall by a descending tide of people.

Hull said he hadn’t seen the sign for the up staircase.

Hull was involved in many firsts for Wonder, sharing Wonder’s first canoe ride and introducing him to Martin Luther King, whom Hull had met earlier.

As Wonder’s talent became more in demand, Hull found himself in the role of de facto road manager, protecting the star from scurrilous promoters.

Most of the time, Hull thought he had the best job in the world. At other times, it was a minefield of influence seekers and flat-out greed, as others sought to use Wonder’s talent to leap-frog their career. It seemed that everyone wanted to write the next big hit for Stevie Wonder.

Hull himself was a songwriter. Two of his songs, “Purple Rain Drop” and “Music Talk,” ended up on the B-side of Wonder hits. He still gets royalty checks.

Hull protected Wonder both emotionally and physically as he grew into a man.

“I had a reputation as Stevie’s mother hen,” he recalled in the book. On one fraught occasion, the “mother hen” vetoed a photo shoot with an attractive young woman who appeared to want to put Wonder in a compromising position.

At the end of Wonder’s tenure with Motown, his relationship with Hull began to show signs of strain as the musician matured and sought more freedom to make his own decisions.

It’s no wonder. Hard as it is to believe, Hull writes about doling out Wonder’s weekly allowance, which was a paltry $2.50 — slim pickings even in the 1960s.

Scores of books have been written about Motown and by its stars and leader, Berry Gordy, Jr. Even a Broadway musical was written on the rise of Motown. But Hull adds something distinctive to the crowded shelf, delving into the hearts and minds of the performers and providing keen insight into what made Motown tick.

Hull’s role in Motown is likely to remain visible at Hitsville, USA, which is being reinvigorated with a projected $50 million infusion to turn the original recording studio into a world-class museum.

“Right inside the door on the left is a time clock (which no one used much). My punch card is still there — the fourth one down,” he said.

Hull will tell his and Wonder’s story 7 p.m., Wednesday, Oct. 24 at the Hannah Community Center in East Lansing, as a guest of the East Lansing Educational Foundation which raises money to support East Lansing schools. The event is free.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here