Pete Gojcaj’s wife, Cile Precetaj, was suddenly deported from Sterling Heights back to Albania this month after living in the U.S. for 18 years.

“People say, ‘why didn’t she just become a citizen?’” he said. “We tried. We spent time and money to no avail. They kept denying her and pushing parts about how she should’ve done something. But when they keep denying you, there’s nothing you can do.”

Gojcaj was among a dozen people who ended a weeklong walk from Detroit on Monday at the All Saints Episcopal Church in East Lansing.

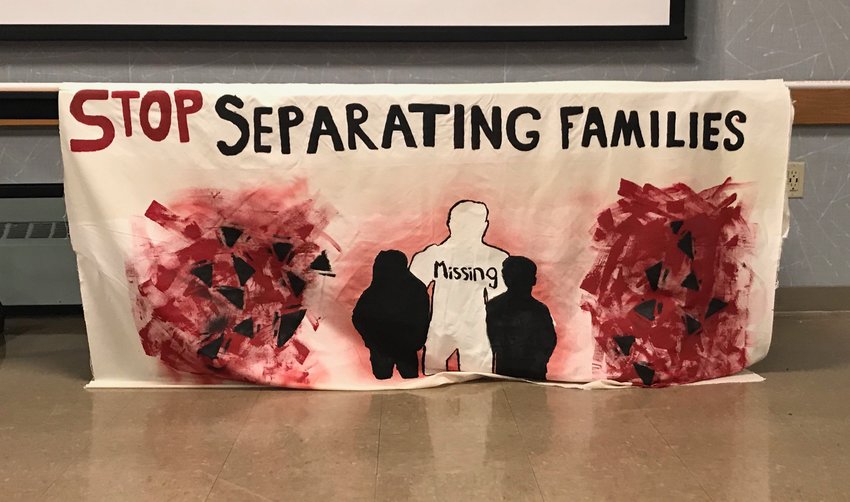

The 90-mile trek, titled the “Pilgrimage to keep families together,” was in support of Ded Rranxburgaj, an Albanian immigrant currently taking sanctuary in a Central United Methodist church to avoid deportation, and other families who faced deportation.

One of the families is Gojcaj’s, whose children — a 16-year-old son and two daughters, ages 8 and 10 — are forced to look at him as both their mother and father, he said.

People will ask him what part of illegal he doesn’t understand, he gives this analogy.

“When someone comes to break into your house, they have to break a window or door to get into your house,” he said. “She didn’t break anything. She walked across. She walked through the checkpoint. She didn’t break anything, but they are breaking up a family. They’re breaking up my children’s future.”

Gojcaj sarcastically said he hopes people feel safer now with his wife deported and can now “sleep with the windows open.” During his speech, Gojcaj’s hands rarely left one of his daughter’s shoulder. “Her future, if not ruined, has been delayed,” he said.

The abruptness of his wife’s case isn’t a rarity.

Doug Fleury, of Madison Heights, said a prayer with his two daughters before breaking the news: Their mother, Laura, was to be deported back to Mexico after 17 years in the U.S.

“Laura was our whole life,” Fleury said. “The girls are lost. If anyone here has grown up without a parent, they know how that feels. I’m lost myself. She was a very big part of our lives.”

Mrs. Fleury was active in both volunteering and organizing fundraisers for her church and her children’s schools. Since her deportation, she’s missed those events and personal ones: birthdays, holidays and her daughter’s junior high school graduation.

The Fluerys saw her a few days after being taken by Immigration through a glass screen in Battle Creek, where she remained for a month “like a prisoner,” said Fleury.

“Immigration targeted us and surveilled our home,” he said. “Our home was watched for up to a week so they knew when we left and when she was home alone.”

He doesn’t know how many agents were there when they picked up is wife or how they approached her. He said all he knows is they were aware they were a family and that the ICE agents didn’t care.

These days, once his daughters are tucked in, Fleury goes to bed alone. He sits in bed with no one to talk to. His daughters spend time at their grandmother’s when he’s busy. They slept there for the first three months after she was arrested. Fleury appreciates the grandparents’ help, but said it just adds to the painfulness of the situation.

“They shouldn’t have to do that. It’s not their job to raise more kids,” he said. “They already did that. A grandparent’s job is to send the kids home loaded up with sweets.”

Fleury paused while talking about his daughters’ current lives and unknown futures. There are no more bedtime stories told by her mother each night. She can no longer tuck them in and kiss their heads, he said.

She can only speak to them over the phone from thousands of miles away.

“This is where I struggle,” he said. “How do I explain this to them? My girls are the reason I get up every day and try to make this right.”

When his wife calls, he has to take a deep breath to calm down before answering. It’s not that he doesn’t want to talk to her, he said. Sometimes he’s just not sure he can handle how much it hurts.

“With the girls next to me and having to talk to my wife in Mexico, it breaks my heart,” Fleury said. A friend wrote a letter to President Trump requesting his wife be allowed stay in the U.S. with her family. The letter was short and sweet.

The response was “terrible,” said Fleury. It listed the reasons deportation laws are in place, and stated the deportation was to keep people safe.

Oscar Castaneda, an organizer of Action of Greater Lansing, said the small turnout at All Saints was a good start to a discussion about the impact of immigration enforcement.

“People need to start listening. It’s a broken system,” Castaneda said. “We want Congress to take action and fix the system but they’re stuck in discussion that doesn’t go anywhere.”

Carmen Kelly is a Colombian immigrant who came to the U.S. more than 40 years ago to obtain a master’s degree in pharmacy. She received a Visa before deciding to stay after getting married.

Over the years, Kelly met dozens of people excited about her immigration status, expressing that their own doctors and friends were also immigrants.

“If we can get immigrants that have degrees and can help, why not have them?” she said. “It’s good people doing good.”

After 9/11, Kelly and her husband, Michael, both now living in Harper Woods, became active again in the pro-immigration movement after previously working for sanctuaries in the 1970s.

They were worried what happened to Japanese people would happen to Muslims, Michael Kelly said. While the concern didn’t happen, he said the issue remains a “real moral crisis that’s corrosive to society.

”The pilgrimage was a good idea because it’s a public way of bringing awareness, but the towns we have been through,” he said. “The support has been inspiring. You can care about something, but once you put your feet on the pavement it makes you more aware of what’s at stake.”

A dozen people ended a weeklong walk, titled the “Pilgrimage to keep families together,” from Detroit to Lansing on Monday at the All Saints Episcopal Church in East Lansing.

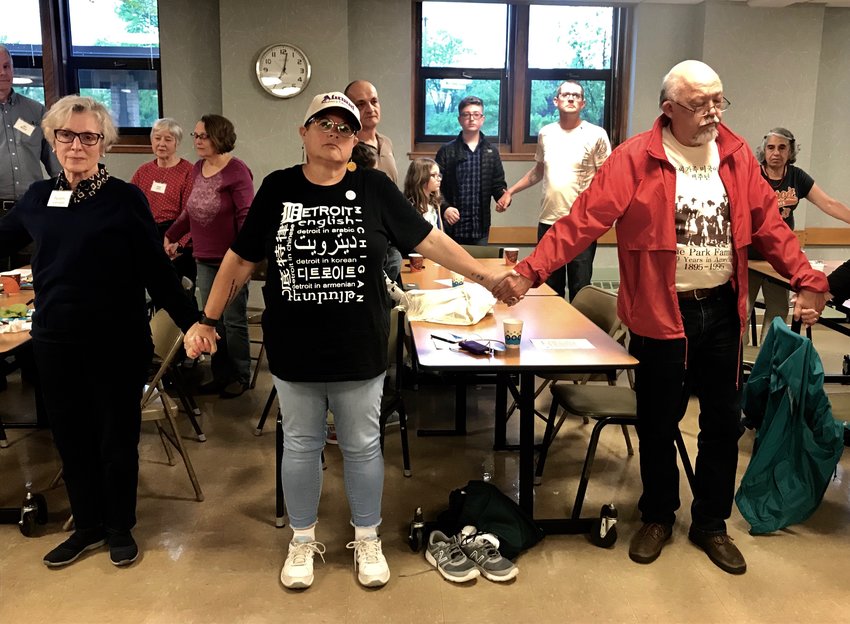

Marchers and supporters hold hands as the All Saints Episcopal Church pastor reads a prayer following the event, which was created to support families affected by immigration policies.

Pete Gojcaj embraces his three children, a 16-year-old son and two daughters, aged 8 and 10, while discussing his wife’s recent deportation from Sterling Heights to Albania.

Pete Gojcaj embraces his three children, a 16-year-old son and two daughters, aged 8 and 10, while discussing his wife’s recent deportation from Sterling Heights to Albania.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here