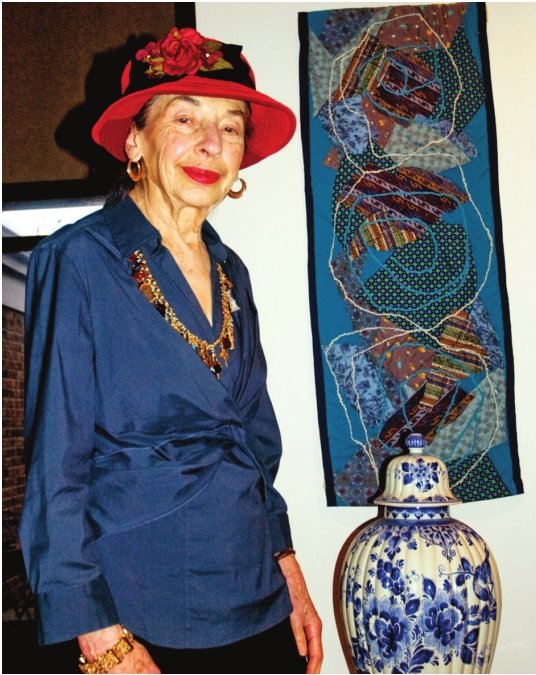

To anyone who attended concerts, plays, gallery openings and other arts events in Greater Lansing in the past 10 years, Selma Hollander was the stunning nonagenarian in the red beret and lipstick, avidly absorbing all the culture from the front row.

But Hollander, who died last week at 101, was only living the final, stylish act of a long and remarkable life.

When Hollander moved to East Lansing in 1958 with her husband, MSU business Professor Stanley Hollander, the couple embarked on a half-century-long rampage through the city’s cultural life, attending nearly every significant concert, play, art show and lecture.

Along the way, they gave generously to dozens of arts organizations, including the Lansing Symphony, the Wharton Center, the MSU College of Music, theaters, libraries, galleries, and individual artists.

After Stanley Hollander died in 2004, Selma carried on with a daily round of social, philanthropic and cultural doings that would have exhausted people onefourth her age.

Until recently, she lived alone in her Okemos townhouse, which she used as a studio, workshop and archive. She didn’t waste much time cleaning the place. She had more important things to do — culture to soak up and art and fashion projects to finish. “My dishes aren’t clean,” she said in a 2011 interview with City Pulse. “You’ll never eat in my house. Simple as that.”

She never lacked for companionship, though. Every impending event brought multiple calls offering a ride. She renewed her driver's license last year just to prove she would, though she had given up driving.

“I never say no to anything,” she said.

“Don’t ever invite me, just to be nice, thinking I’ll say no, because I won’t.”

Hollander was born in Brooklyn on June 18, 1917, into a middle-class family. Her father was a postal carrier.

By the time she graduated from Thomas Jefferson High School, she was already in a category apart from most of her husband-hunting female friends. She aimed for independence, but it wasn’t easy. She quit NYU after three grinding years in the mid-1930s, the height of the Depression.

“Economics, sociology, government — it went on and on, plus stenography, typing, bookkeeping,” she said. “There wasn’t a single elective. I couldn’t bear it.”

Stylishness was more her style. Her mother, a milliner, made beautiful clothes for herself and her daughter.

“I used to dream of sewing clothes and designing and things like that, but not being an artist,” she said.

In her late teens, she found pay dirt at the Post Office, acing the entrance exam and starting as a clerk, boxing mail at night, to her parents’ disapproval.

Two years later, she got a plum secretary position and was earning as much as her father. She stayed with the post office 17 years.

“Three weeks’ vacation, 13 days’ sick leave — and I was never sick,” she said. The years at NYU weren’t wasted after all.

Right away, she bought a car and took up golf.

She bought a set of Babe Didrikson golf clubs and let her inner Babe out — athletic, poised, independent, like the groundbreaking golfer and multi-skilled athlete of the 1930s.

Hollander’s sartorial slam, powered largely by splashes of red and killer accessories, came naturally. “My mother wanted me to dress beautifully. She made all these hats for me. I always had a hat for everything.”

She started going to Camp Tamiment, a summer resort in upstate New York popular among middle-class Jewish workers.

(“A boy-meets-girl place,” she called it.)

One Saturday afternoon during Rosh Hashanah of 1956, she was thrown into a golf threesome with two men. One was a young professor and specialist in marketing at University of Pennsylvania’s business-focused Wharton School named Stanley Hollander.

“I didn’t fall in love at first sight,” she recalled with a shrug. “Sorry, but he did — I didn’t.”

Stanley proposed to Selma about a month after they met. She found the whole idea “incredible.”

“What if the marriage didn’t work? I’d be giving up my security.”

But Stanley was urbane, intellectually voracious and doggedly pursued his passions — Selma foremost.

“He was the last Renaissance man,” she said. “He was brilliant as a scholar and had the most incredible sense of humor. He had everything.”

The couple married Dec. 16, 1956, and went to Bermuda on their honeymoon. They came to East Lansing in 1958, when Stanley came to MSU’s Marketing Department as an associate professor.

“Apparently, he wanted to get away from his mother,” Hollander said.

The Hollanders quickly became fixtures of the Lansing area’s cultural scene.

This, she said, was when her life “really started.”

The couple traveled to Europe and soaked up every exhausting minute of the Chautauqua Music Festival in New York. During a stay in London, Selma learned lacemaking, yarn spinning and ceramics. One summer, Stanley did research at the United Nations while Selma enrolled in Rutgers University. They avoided high Manhattan rent by living in Selma’s dorm room as student and spouse.

Most important, they treated their new hometown as if it were Chautauqua or London, absorbing the local culture to the fullest and pushing the envelope where it fell short.

“The university is here,” she said. “How do you have a university here and not take advantage?” To her surprise, Hollander started taking art classes at MSU. “My inspiration was, I had to do something,” she said with typical self-deprecation.

Her first class was full of “junk little craft projects” that didn’t interest her.

Undaunted, she took a series of studio art classes and started getting 4.0 grades. She ended up with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts, became an art instructor and branched into jewelry, textile art, painting and her most recent passion, collages.

In the Hollanders’ heyday, they went to almost every Wharton Center production. As the audience cleared and the house lights came back on, they were often seen sitting in the front row, chatting. More recently, Hollander would just chill in the Green Room after a concert, waiting to chat with the musicians.

She didn’t seem to care much what was on the program.

“Beethoven’s Sixth, Fifth, Ninth — I just go and I enjoy the evening or I don’t enjoy it,” she said. “But most of the time it’s good.”

While many big cultural donors are hoping to lure artists to their homes for private parties and concerts, the Hollanders’ checkbook followed their hearts and minds. They often supported less popular cultural offerings, including modernist sculptures and a new music concert series.

Selma Hollander kept the philanthropic tradition alive well after Stanley died. A gallery in the ultramodern Broad Museum is named after her and Stanley.

Like many long-time donors to the university, Hollander was skeptical of the project at first, but a tour of the building helped change her mind.

“It’s fantastic,” she said in 2011. “I’m just sorry I’m not going to be around for a long time, because I would enjoy the art very much.”

Fortunately, she lived long enough to attend many openings and exhibits at the Broad, and her philanthropy didn’t stop there. Her support of the MSU College of Music reached another peak last November, when she donated $1 million toward MSU’s new Music Pavilion to build a recital hall.

Along the way, Hollander never stopped creating. In 2017, at 101 years old, she was astonished (or pretended to be) when about 20 of her colorful, abstract serigraphs, or silk screen prints, were chosen for an exhibit at the Lansing Art Gallery — her first art show.

“An exhibit of my work! It never crossed my mind,” she said in a 2017 interview. “But I never say no to anything.”

That was Hollander’s advice for young people in her 2012 commencement address at MSU, another first for her, at 95.

“You just don’t close doors. They may open again, but not likely, and that’s the end of it.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here