On Feb. 11, 1965, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. came to MSU to deliver a speech on education. It sounds routine, but there was no such thing as a routine speech by Martin Luther King.

The enriching root of education and its potent fruit, voter registration, were life and death matters in the segregated South. King was determined to recruit help. Although his responsibilities were multiplying by the day, he wedged MSU into a grueling schedule of meetings, speeches and sermons.

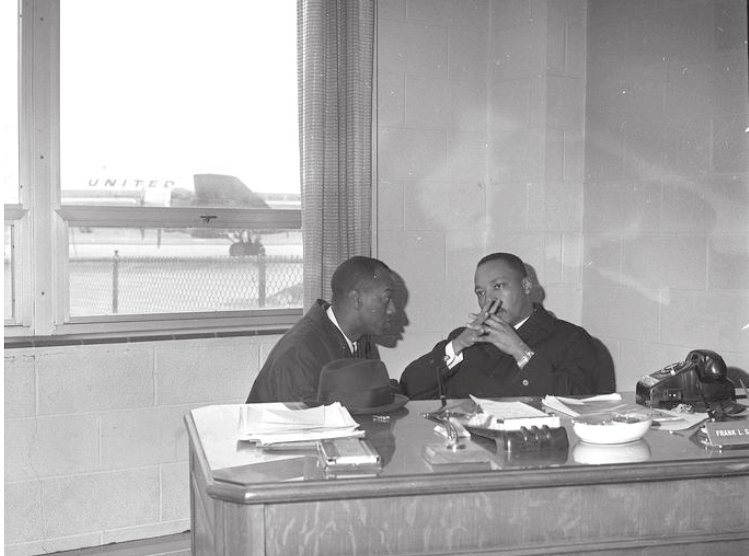

“When I picked him up at the airport, he wasn’t feeling too well,” MSU Professor Robert Green recalled. “He was tired and had a sore throat. It was the only time I ever saw him ill.”

Over 50 years later, King’s sore throat was news to former Lansing Mayor David Hollister, then a teacher at Eastern High School.

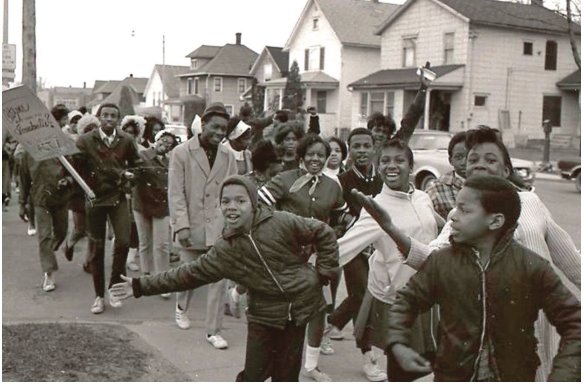

Spellbound by King’s oratory that day, Hollister and dozens of others volunteered to teach underserved students in the South and register people to vote. They ended up facing down KKK thugs in Mississippi that summer.

“That day changed my life,” Hollister said.

Giant Steps

The speech at MSU was the last of at least three visits King made to the Lansing area. In 1954 and 1957, King came to Lansing at the request of his uncle, the Rev. Joel King, pastor of Lansing’s Union Baptist Church. The 1957 speech drew thousands of people to the Lansing Center.

By 1965, King was a national force with his finger on the hour hand of history, but he still sweated the details. He came to MSU to kick off the first all student-run educational outreach program in the country — the Student Education Program, or STEP. He made the fund-raising pitch to 4,500 students, faculty and community members at the MSU Auditorium.

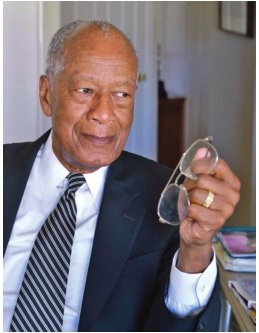

Green, a professor emeritus at MSU, where he was the dean of urban development, and keynote speaker at MSU’s King commemoration at the Erickson Kiva Monday, remembers the day vividly.

Green drove King from the Lansing airport to his office at MSU, on the second floor of Erickson Hall, and made him hot tea with lemon.

Green had a lot of questions, but King didn’t talk about himself.

“He was always turning it on you,” Green said. “He wanted to know about me, about my job, about MSU, how were they treating me. He asked about my kids.”

To his amazement, Green noticed King quicken his step, lose the cough and grow more animated on the walk from Erickson to the auditorium.

“He became invigorated, alive, and gave a great speech,” Green said. “He didn’t have time to get sick.”

King didn’t confine his remarks at MSU to the STEP program. Never one to shy from big themes, he urged the assembled students and faculty to adopt a “world brotherhood perspective,” denounced the notion of superior and inferior races and called for worldwide action to end segregation.

King called for new civil rights legislation and name checked MSU President John A. Hannah, who was appointed chairman of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 1957 by President Dwight Eisenhower.

In the wake of assaults and harassment, King urged action on the Civil Rights Commission’s recommendation that federal staffers handle voter registration in the South.

Green couldn’t have refused King’s call even if he had wanted to. He got the OK from Hannah to take a leave to work for King from 1965 to 1967 as educational outreach director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Working for King wasn’t a cubicle job. In tense times, Green helped King organize the 1966 March against Fear in Mississippi.

His time with King was an eye-opener. “He was so adamant about not being afraid to die,” Green said.

In Green’s book, “At the Crossroads of Fear and Freedom,” he recalled driving in the South with King, his confidant Andrew Young and three other associates. When they stopped at a red light, a white gas station attendant recognized King in the front seat.

The man walked up to the car, pulled out a gun and held it to King’s head.

“I love you,” King replied calmly. The would-be assailant walked away. It took years for Green to wrap his head around King’s surreal serenity.

“Listen to his old sermons,” Green said. “There are a lot of them on line. King always talked about death. It was his way of purging himself of fear.”

When traveling, Green and King’s other associates begged him to sit in the back of the car, flanked by aides, but King resisted.

“He said, ‘You guys can’t protect me. John Kennedy had the Army, the Air Force and the Secret Service, and they got him. I don’t have all that. When they’re ready for me they’re going to get me, and I’m prepared to die.’” King teased his friends and associates about their solicitude.

“He would say, ‘You guys are so worried about me getting shot. One day, someone will shoot at me and miss and hit one of you,’” Green recalled. “And he started giving a mock eulogy for his ‘good friends.’”

‘I’m signing up’

On the day King came to MSU, an unknown MSU student changed David Hollister’s life by handing him a flier.

The former Lansing mayor, then a teacher at Eastern High School in Lansing, made his way to the MSU campus to hear King.

“I was mesmerized,” Hollister said. “I could tell he was speaking extemporaneously.”

Hollister was so moved by the speech that he rushed to get near the rear exit to meet King when it was over.

“I shook his hand, looked in his eye and said, ‘I’m signing up,’” Hollister said. “I didn’t realize what that would mean, but it was a brief encounter, less than a minute.”

Hollister spent the summers of 1966 and 1968 teaching math, history and government at underserved schools in Mississippi, for no pay.

“Oh my God, it was life-changing,” Hollister said. “You can read all you want to about segregation, but we were harassed by the Klan and supporters trying to terrify both the volunteers and the students. That experience fundamentally impacted everything I did in 50 years of public service.”

Burning message

Martin Luther King Jr. was a young Ph.D. student in theology at Boston University when his uncle first invited him to speak at Lansing’s Union Baptist Church on Jan. 3, 1954.

Joel King, the younger brother of Martin Luther King Sr., was pastor of Union Baptist — now Union Missionary Baptist Church — in southwest Lansing for eight years in the 1950s. The old church building, at the corner of Logan (now Martin Luther King Jr.

Boulevard) and St. Joseph streets, is no longer standing. Joel King also ran, unsuccessfully, for the Lansing City Council.

Starting with this comparatively lowkey appearance, King’s three Lansing visits would climb sharply in urgency and scale.

“Nothing so eventful on that day — other than the climax of a rally for beautifying the interior of the church,” Joel King wrote in his invitation to Martin Luther and Coretta King.

The 1954 visit was put off until the first Sunday in March, when Joel King made a more urgent request in a second letter. “I am asking that you would accept the engagement, as it would mean much to you and me,” he wrote. “Remember that this is a cross section of Negro and White. Usually the message is from one half hour to one hour long.

Would like for you to bring them a burning message, centering around some of our present-day problems.”

King spoke March 7 at the morning service. That day, King was also scheduled to address the Lansing branch of the NAACP. The church has no record of the text of King’s speech, but church member LaVerne Wilson is compiling a history of King’s ties to Union Baptist, Joel King and Lansing.

“I found it amazing that King has all these ties to Lansing, and yet it’s hardly known or talked about,” Wilson said. “The Martin Luther King luncheon is in its 34th year, but I don’t know how many people realize there’s more history of Martin Luther King in Lansing.”

By 1957, King’s stature in the moral, spiritual and political life of the nation had grown considerably. In May of that year, King would deliver his first national address, “Give Us The Ballot,” at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, D.C.

This time, Joel King had a bigger forum in mind for his nephew. “I feel it’s time for you to come to us,” he wrote Martin and Coretta King from Lansing. “People of all races are continually asking about your coming. I would like to make this one of the finest programs that they have had at this huge new Civic Center Auditorium.”

Atomic cannon

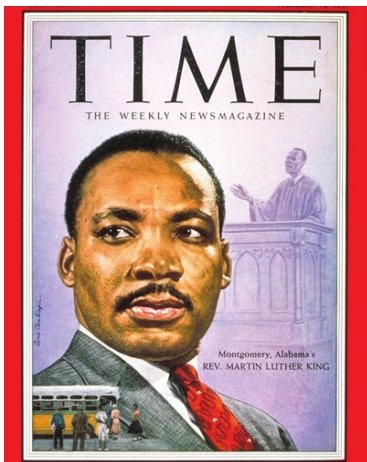

On Feb. 17, 1957, King spoke to over 3,000 people at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium of the 2-year-old Lansing Civic Center, urging a vigorous but peaceful fight against segregation. His national profile was in the ascendant. The next day, his face would appear on the cover of Time Magazine. Three days earlier, King became head of the Southern Leaders Conference, later the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Donations at the Lansing speech went to the victims of racially motivated bombings of homes and churches that had recently wracked the South, including the bombing of the home of the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth in Birmingham, Alabama, the previous December.

King gave the Lansing audience a vivid description of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott that made national news two months earlier.

“They decided it was more honorable to walk in pride than ride in humiliation,” he told the group. “They substituted tired feet for tired souls.”

Headlines from Hungary were dominating the news at the time. The previous November, Soviet troops crushed a student-led revolution in Hungary, killing thousands and sending hundreds of thousands into exile.

King knew that Americans were riveted by events in the Eastern bloc and watched with horror as the tanks rolled into Budapest. He admonished the crowd to remember the plight of their own African-American brothers and sisters at home.

“If the United States is to be a first-class nation, it can no longer have second-class citizens,” King declared. “It is a puzzle to us why the government of this nation cries out against Communist oppression and not against oppression of people here at home.”

Michigan Gov. G. Mennen Williams, a strong advocate for civil rights and racial equality, attended the speech with his wife. King said Americans would make a “great move” if they elected Williams president.

When King was finished, Joel King invited Williams to speak. The bow-tied governor pleaded that his oratory, compared to King’s, would come off like a “pop gun compared to an atomic cannon.”

Evergreen words

Every year, when the King holiday comes around, people find the question irresistible: What would King be saying today?

The question is tragically easy to answer.

Chances are, anything King said 50, 60, or 70 years ago is doubly or triply relevant now. Consider this snippet from an editorial King wrote in the Morehouse College student newspaper — in 1947.

“At this point, I often wonder whether or not education is fulfilling its purpose,” King wrote. “Education must enable one to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.”

Robert Green heard King say such things first hand.

“There’s a lot of unreal stuff being said today,” Green said. “King would have been in the forefront now of challenging the many untruths that are being spread around the country, especially about poor people, about immigrants.”

King also hammered at the need for early childhood education.

“That’s a big deal today,” Green said, “but he talked about it 50 years ago — making sure kids can read and process information.”

While in Lansing, King talked to Green about lynchings and beatings of black men who were organizing voter registration in the South. In 1965, King was preparing to lobby President Lyndon Johnson to sign voting rights legislation.

Green said King would have been “very upset” with recent attempts to erode voting rights in several states, and would have denounced 11th-hour legislation in Wisconsin and Michigan aimed at restricting the powers of incoming Democratic officeholders.

“If he were alive today, he would call together black, white, Hispanic, Native American leaders, like he did for the poor people’s march, and say, ‘This is wrong,” Green said.

In Green’s view, recent protests by student and professional athletes like Colin Kaepernick would also have gotten King's attention.

“Dr. King admired Muhammad Ali because he spoke out on human rights issues and denounced the Vietnam War,” Green said. “He admired Ali because he was fearless inside and outside the ring. He would have been 1000 percent behind Colin Kaepernick. He would have respected him, met with him, encouraged him and supported him.”

The list goes on and on. It’s so hard to keep up with Marin Luther King, even today, that it would almost be dispiriting, were not King so good at lifting them back up.

“I constantly think about him,” Green said. “I feel that he’s there. He used to quote William Cullen Bryant a lot: ‘Truth crushed to Earth will rise again.’”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here