At most science fairs, you’ll see molecule chains, astronomy charts and, if fortune smiles, fine subsoil classifications.

Only one student competition is expansive enough to welcome angry bacon and rapping wasabi.

Hustling from venue to venue on a fast bike, I could barely sample a tiny fraction of Friday’s madness at MSU, where the 2010 finals of Odyssey of the Mind competition were in full freak flag flight.

The pattern was the same everywhere on campus: a dozen or so excited kids in identically colored T-shirts, followed by one or two tired, bemused, 40-ish adults.

“Look, it’s air conditioned!”

An estimated 20,000 students, family members, and coaches — 813 teams from 15 countries — criss-crossed campus from Wednesday through Saturday like army ants in funny hats, scouring the ecosystem of every drop of ice cream and crumb of pizza.

Between forays to local restaurants, the MSU Dairy Store and the IM West outdoor pool, teams of students from kindergarten through high school competed to solve creative “problems” with elaborate guidelines but no set solution.

Some Odyssey problems called for technical skill — NASA is a sponsor — but others were roughly two percent science and 98 percent sugar buzz theater.

A problem called “Food Court,” where students put a food item on trial, was little more than an invitation to dress up like a fish (gum wrappers make nice scales) or wear a creampuff coif.

Apples were tried for choking people. Fish were in the dock for being smelly. Bacon was mercilessly grilled. (And looked none too happy about it.)

A high-energy group from Naksaeng High School in Sungnam, South Korea, took the problem around every anatomical bend and then some. Three foods (shrimp, wasabi, and pudding) danced, rapped and climbed into a giant face made of painted and stacked cubes. As their journey went on, the cubes were rotated to portray the esophagus, stomach and large intestine. Despite some light banter about peristalsis, everyone knew where this was headed.

The three foods distracted the audience from thoughts of the end by playing out a gut-wrenching love triangle. Finally, Judge Green Tea (a leafy mandarin with stilt arms) found “pudding” guilty of artificial color and sentenced him to be excreted.

This occasioned a disgusting, but fleeting, costume change. When the crowd burst into applause at the end, “pudding” discreetly tossed his poop hat behind the set and took his bow bareheaded.

An off-duty Odyssey judge, Deborah Teague of Arkansas, was in the back, goggling at the spectacle. It was Teague’s first trip to the World Finals.

“I’d like to know what the customs people said when they saw some of this stuff,” she said. “What do you have to declare? A giant mouth?”

To competition founder C. Samuel Micklus, a.k.a. “Dr. Sam,” the wild costumes and concepts lubricate three prized traits: teamwork, fantasy and flexibility.

“Problem solving is the highest form of learning,” Micklus declared in his book on the competition. “We raise the bar by adding creative thinking.”

Micklus is the Walt Disney, Henry Ford, Gautama Buddha and Sam Walton of “Odyssey.” While teaching technology courses at Rowan University in New Jersey in the 1960s and 70s, he got tired of seeing bright students stifled by teachers “who are convergent in nature,” i.e., expect a single correct answer to a question.

Micklus found that smart kids are bored or disenchanted with low expectations and barely-get-by curricula.

“There is a misconception that these kids can take care of themselves,” he wrote. “I wouldn’t be surprised if their dropout rate is as high or higher than the rest of the school population.”

In 1978, teams from 28 New Jersey junior and senior high schools met in the first Odyssey competition. Over 40 years later, a concept born of 1960s pedagogy has become an international juggernaut.

In this year’s most high-profile problem, “Nature Trail’R,” the students had to build a human-powered vehicle that could overcome obstacles and clean up its environment, among other tasks.

Every team got to do an eight-minute riff on the theme. The Breslin Center storeroom looked like the prop department from a Terry Gilliam movie, with fantastic chariots, buggies, carts and velocipedes parked everywhere.

A team from Halstead, Kansas was fussing with a pink contraption made out of 20 bicycles.

Each linkage had three sprockets, said team member Matthew Rodenberg, not because they were needed, but “just for complexity.”

No sensible adult would come up with a machine like that, but that’s the point. Coaches can only ask questions, never give hands-on help.

“So often, parents do science fair projects for them,” commented judge Heather Hanks from Florida.

“They do their own things in a society where so often, parents coddle kids. Here, if they want to weld something, they have to weld it.”

The imaginary settings for problem solutions ranged from a donut planet (watch out for the hole) to the present-day Gulf of Mexico.

A team from Cherry Lane High School in Austin, Texas, trundled around the floor in a cart steered by turning a wooden wheel parallel to the floor, a la Sit ‘n Spin.

When the team first built the cart, the driver had to spin the wheel dozens of times to move the cart one inch.

“We learned about gear ratios,” team member Austin Bates said.

With their big moment behind them, the team was headed back to Akers Hall for another round of foam-rubber sword fighting with a sister team from Singapore. Because they have 10 players and only four swords, both teams have worked lateral sword passes into the game.

As Dr. Sam would say, “the purpose of creative problem solving is the transfer of learning to new situations.”

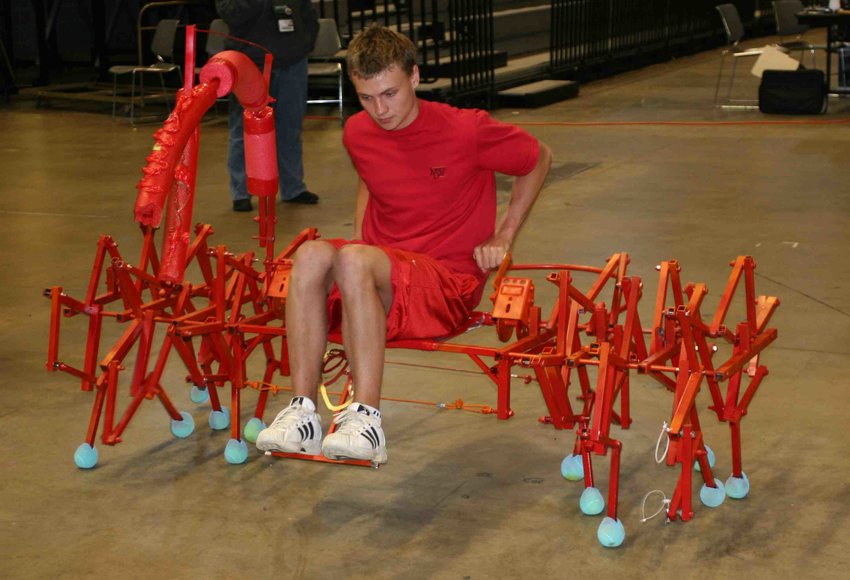

One of Friday’s “Trail’R” highlights was an astonishing array of tubular metal, cranked by hand, that moved forward on gentle tennis-ball feet.

The bright red crab-walker played a key role in a timely oil-spill scenario from Oakton High School in Vienna, Virginia.

“Look man, no wheels!” yelled crabman Carter Scharer as the team began.

In addition to hairsbreadth engineering, the Oakton scenario involved a student in a starfish suit, a penguin with oil-encrusted feet, Shakespearean couplets and satirical references to Halliburton and the EPA.

The crabwalker had over 100 moving parts, each one cut to a .15-inch tolerance.

The judges were mesmerized. One judge asked to ride the machine himself. At the debriefing, Scharer told them that when he first sat on the frame, it sagged half an inch and froze the whole works. The crew installed a steel cable under the seat to flex the frame tighter.

“What do you plan to do with it now?” a judge asked.

“Sell it on eBay,” piped a voice.

In early afternoon, the food court at MSU’s International Center was jammed. Among the hungry was a team of American military-dependent kids from Gielenkirchen Elementary in Germany. Most hadn’t been to the United States in years.

Their problem called for them to act out a historic rediscovery, and they chose the Aztec temples in Tenochtitlan. But in true Odyssey style, the problem also called for them to imagine some present-day artifact being discovered in the future.

They chose the world’s biggest park bench — the serpentine mosaic bench in Barcelona, designed by Antoni Gaudi.

At a conventional science fair, students might hypothesize that the bench would be covered in volcanic ash or flooded by rising seas.

But this is Odyssey of the Mind.

“It’s hidden by a leprechaun,” coach Stephanie Starkey explained. “She’s a loner, she likes to live by herself and uses her magic to hide it.”

The “spirit of the problem,” in the judges’ phrase, determined the spirit of the trash left at each of the MSU venues Friday afternoon.

By late afternoon, the bins at Wilson Hall were piled with Promethean leftovers from “Food Court:” boulder-sized strawberries, a four-foot-wide satin cherry pie, atomically mutated grapes, and bon-bons the size of soccer balls — because they were made of soccer balls. The parking lot near Spartan Stadium was heaped with chunks of castle turrets, wall sections, and street scenes, all backdrops for “Nature Trail’R.”

All these props had been sweated, argued and fussed over for months, as each team made its way to the finals. Now they were useless as discarded bug exoskeletons.

The young minds responsible for them were ready to grow more.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here