On a subzero night 70 years ago, tears were streaming down the face of Geneva Kebler Wiskemann. She can vividly recall the night of Feb. 8, 1951. She stood in front of the Estes Leadley Funeral Home and gazed across Walnut Street as smoke and flames engulfed the State Office Building, where she worked as a circulation specialist for the Library of Michigan.

Wiskemann, who will be 94 on Monday, said she first learned there was a fire while shelving books on the first-floor reading room, which has high ceilings and a glass over-floor on its west end.

“Smoke began coming out of the registers,” she said.

Along with 1,300 other state employees, Wiskemann was evacuated but returned later in the evening with George Kebler, her future husband. She cried tears of despair for the more than 500,000 rare books and archival material, which were at risk from the slow-moving fire and subsequent water damage.

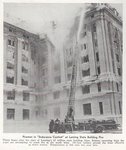

“It was so cold out that water froze like crystals when it was shot from the firehoses,” she said.

The six-story office building, now known as the Elliott-Larsen Building, was considered state-of-the-art when it was completed in 1922 at a cost approaching $3 million. An additional floor was added in 1923 — when the building was named after 19th century U.S. Sen. Lewis Cass — and an attic was converted to a mezzanine. As the only state building other than the Capitol, numerous government departments occupied its halls including the Library of Michigan, the State Banking Commission and the Michigan Highway Department. The neo-classical U-shaped building was designed by local architect E.A. Bowd and constructed using reinforced concrete with marble staircases and concrete pillars supporting the floors. It had entrances on all four sides.

An alarm notifying the Fire Department was pulled at 12:40 p.m., while most workers were at lunch and cashing their paychecks. Firefighters arriving on the scene were confounded by heavy smoke and intense heat from the mezzanine level between the sixth and seventh floor, which held state records in locked wire cages and housed the Highway Department’s microfilming unit.

Wiskemann said a variety of individuals who were still on their lunch break held keys for the different wire cages, thus making them inaccessible to firefighters.

The first firefighters on the scene soon asked for smoke masks and a three-alarm fire notice was sent out, calling more than 110 firefighters to the scene. Reports at the time said the Fire Command considered using a former burglar to dynamite a hole through the roof, so water hoses could be aimed directly at the fire.

By nightfall of Feb. 8, the fire was still raging and Battle Creek, Flint and Jackson sent their aerial trucks and a pumper to help out. Flames began erupting from the seventh floor at about 9:45 p.m. and hoses were stretched out on three 100-foot booms provided by two local construction companies, the Christman Co. and Granger, in order to reach the top floors. By 2 a.m., equipment began arriving from Grand Rapids, allowing firefighters to pour 5,000 gallons per minute on the fire. Lansing’s Fire Engine No. 1 was damaged by ice and removed from the scene.

During the first day of the fire, Gov. G. Mennen Williams inspected the building twice, once making it all the way to the seventh floor and walking directly into the smoke-filled hallways. He was asked to leave because of the obvious danger.

A contemporaneous news report in the Lansing State Journal quoted a member of the entourage as saying, “It was like a Democrat walking into a convention of Republicans or Shadrach into the fiery furnace.”

Courageous state employees and the state police scurried to cover furniture, equipment and records with tarpaulins on the first five floors, not knowing that the mezzanine floor was at risk of collapsing into the floor below. At 7:30 p.m., a portion of the seventh floor in the north wing collapsed onto the M-6 level, providing an opening for the fire to spread.

The next morning, Friday, Feb. 9, a vault on the seventh floor’s south wing crashed through to the M-6 level, destroying huge amounts of historical records and books.

Fighting fatigue, bitter cold and smoke inhalation, numerous firefighters were hospitalized, including the fire chief. During the fire, the Red Cross, Salvation Army and Box 23 — a support group for the Lansing Fire Department that grew out of the spectacular Kerns Hotel fire in 1934 — provided warm socks, gloves, coffee and food to the exhausted and freezing firefighters.

By Saturday, the fire was mostly extinguished, and members of the fire marshal crew toured the building and assessed the damage. On Saturday, some astounding news was revealed when Richard Shay, a 19-year-old Highway Department employee, admitted to intentionally tossing a match into a wastebasket, thus igniting the disastrous fire. Shay had hoped that by starting a small fire, extinguishing it and admitting fault, he would be excluded from the draft for the Korean War. Later, Shay’s alibi fell apart and he plead guilty to arson. He served three years, a year less than his four-to-10-year sentence. He resided briefly in Lansing before moving out of state.

When the fire diminished, the Christman Co. and Granger began securing the building. On the sixth day, while the fire was still smoldering, moving companies began relocating furniture and vital records to other sites across the city.

As the fire progressed on Thursday, temperatures plummeted to 10 degrees below zero, giving the building’s appearance the look of a giant ice sculpture spewing frozen crystals from all of its windows and doors. The fire made national news and two radio stations broadcasted remotely from the location. Gawkers became such a problem that local police and the state police were stationed at the site.

It was determined the mezzanine and the seventh floor were damaged beyond repair. Today, the original building has only six floors.

Finger-pointing began while the fire was still raging, and a several-year-old report by the state Fire Marshal was dragged out, which recommended numerous safety changes on the mezzanine including fire suppression equipment and enclosing stairwells. None were implemented due to cost concerns. Legislators began calling the State Capitol a firetrap.

By Saturday, state librarian Loleta D. Fyan began assessing the loss of rare historical records and books. One item presumed damaged was a rare edition of “Audubon’s Birds of North America,” along with a complete set of U.S. Supreme Court decisions and rare historical newspapers. It was estimated that 500,000 volumes had been damaged, some frozen in cakes of ice. The collection of art reproductions of masterpieces by Michigan artists, which was loaned to schools, literary societies and associations, was also damaged.

Wiskemann said while touring the building after the fire was extinguished, she noticed the Audubon was untouched by fire but water was slowly dripping on it. She and another employee rescued it.

“Overall, the Archives and the State’s Historical Commission lost the most. Unique, one-of-a-kind materials, even the catalog perished,” she said. Wiskemann said everything from Civil War diaries to early 20th century records of administrations were lost.

The state librarian led a herculean effort to save the rare books and documents by transporting them to the fieldhouse at the Boys Vocational Center, where the books would be dried out. Librarians, according to Wiskemann, worked around the clock turning pages of waterlogged books, as giant fans blew air across them. Unfortunately, the state’s traveling library, which was stored in the basement, was completely lost to water damage. Today, numerous books in the Library of Michigan collection have statements pasted onto them stating damage may be due to the fire.

An untold number of books and records were lost, and Wiskemann recalled walking through the fire-ravaged library and seeing what appeared to be ash-covered books. “As we walked by them, the currents from our movement caused them to totally disintegrate before our eyes. It was eerie,” she said.

Officials anxiously awaited the opening of a special steel vault, which held Michigan’s most important formative statehood documents. The documents were found relatively unscathed and the safe manufacturer, Mosler Safe Co., used the fire in an ad campaign to promote the durability of its safes.

Michigan began the rebuilding process immediately by lopping off the mezzanine and top floor and closing the north and south entrances. The building reopened two years later after receiving $32 million in renovations, and it was renamed the Lewis Cass Building after Michigan’s first territorial governor. In 2020, it was renamed the Elliott-Larsen Building as part of a national movement to rename buildings and remove monuments that honor leaders who owned slaves, as Cass did. The building was added to the National Historic Register in 1984.

The fire still stands as Lansing’s most devastating in terms of structural loss, but fortunately no lives were lost — unlike Lansing’s other destructive fire at the Kerns Hotel in 1934, which claimed 34 lives, including seven legislators.

Wiskemann went on to work for more than 30 years at the Archives of Michigan and became a force in preservation and local history and has donated her family collection to the Archives.

After working in the building on cleanup duty following the fire, Wiskemann has not returned to the building.

“There are too many spirits in there for me,” she said.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here