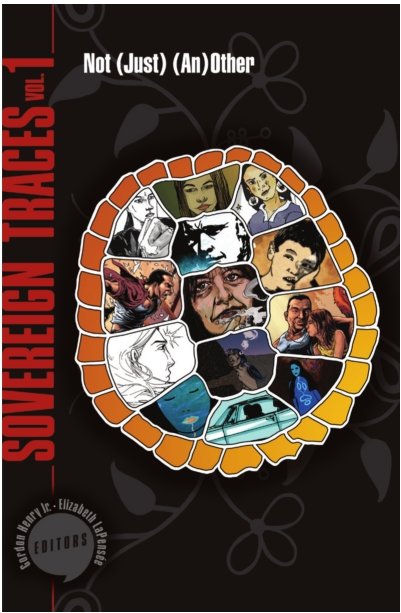

The nine selections in the book include contributions by major North American Indian writers coupled with a variety of contemporary, sometimes comic book style illustrations by U.S. and Canadian artists.

Authors such as Louise Erdrich, Gerald Vizenor and Gordon Henry Jr. are represented in the illustrated collection which will become a continuing series.

Henry, who is an enrolled member of the White Earth Chippewa Tribe of Minnesota and teaches American Indian Studies at Michigan State University, serves as series editor. His novel, “The Light People,” won the American Book Award in 1995.

Another MSU professor, Elizabeth LaPensée — an award-winning writer and artist Anishinaabe from Baawaating, is co-editor. She illustrated and colored Erdrich’s “The Strange People.”

Although this is MSU Press’ first entry into the graphic novel format, the new series has been under consideration for some time, according to Henry. But, it took a while to put together the lineup of authors and pair them up with illustrators.

“It is something we wanted to do reach new audiences with a new way of delivering Native stories,” he said. “The graphic format is a perfect fit for the oral tradition of Indian storytelling.”

Henry’s short story “The Prisoner of Haiku,” illustrated by Neal Shannacappo, is an imaginative look at the negative impact of American Indian boarding schools. A young man loses his voice when he is tortured after refusing to give up his native language. He becomes an accomplished sculptor, but then finds another voice when he becomes an arsonist that targets liquor stores — a cultural anathema for American Indians.

American Indian boarding schools were initiated in the late 1800s to early 1900s to assimilate children into a white culture by “taking the Indian out of the Indian.” American Indian children were taken from their parents, sometimes forcibly, and sent to “schools” often run by religious organizations.

Mental and physical abuse abounded and families were often separated for life. Michigan has several American Indian boarding schools, most notably the Mount Pleasant Indian Boarding School and the Holy Childhood Boarding School in Harbor Springs, which operated into the 1970s. No one is really sure how many American Indian children were housed at the schools, where many children died or ran away never to be seen again.

Make no mistake — the stories and illustrations in this volume aren’t pleasant strolls down a romanticized Indian trail in moccasins, but rather are a frank look at the modern American Indian way of life.

Henry calls the bar scenes in Joy Harjo’s “Deer Dancing,” illustrated by Weshoyot Alvitre, “pretty gritty.” In “Deer Dancing,” a typical bar scene at an off-reservation bar is interrupted when a beautiful young woman enters and dances naked. Is it a dream? Was it a deer? A trickster or maybe a modern myth?

Many of the stories in the collection alternate between reality and something American Indian story tellers are very familiar with— magic realism.

All the authors in the collection submitted work at no cost.

“We paid the artists, not the authors,” Henry said.

The styles of art are as varied as the stories, but each artist has connected with the themes by not overwhelming them. This can be seen from the wallstyle petroglyph-like art used in part by LaPensée to illustrate Louise Erdrich’s poem, “The Strange People,” to the more contemporary superhero-style art of Scott B. Henderson, with colorist, Donovan Yaciuk, in the flash-bang story, “Mermaids,” of Richard Van Camp, a member of Tticho Dene from Fort Worth.

In a prelude, Henry describes his and LaPensée’s desire to recognize and develop Native Literature and the “profound intellectual and imaginative cultural legacies of Indigenous people and communities.”

Henry sees the medium of the graphic novel “doing some amazing things” for telling American Indian stories. This past winter the third annual Indigenous Comic Con was held with the focus of adding American Indian cultural influences rather than the previous “sidekick mentality” (think Lone Ranger and Tonto) to comics and showcasing writers and artists.

On the downside, an American Indian was portrayed as a superhero by Eugene Brave Rock in a recent Wonder Woman movie. It was a major breakthrough, but Brave Rock wasn’t pleased that his character’s name in the movie was “Chief,” but at least he didn’t have to clean up after a masked man.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here