Todd Heywood has won state and national awards for his reporting over his 30-year journalism career. He has also been living with HIV since 2007. His work has been cited by the United Nations Commission on HIV and the Law, the U.S. House of Representatives and in numerous state legislative and administrative memos related to policy and HIV. Heywood also hosts conversations at universities in the state to discuss a variety of topics related to HIV and the law.

Because of editing errors, this story carried two mistakes. One of them was in connection with what motivated a local resident, Doak Bloss, to engage in pioneering efforts to assist those afflicted with HIV. The story attributed it in part to his boyfriend’s death. The boyfriend is still alive. City Pulse regrets the error.

The other mistake was a typographical error giving the wrong date for when Dr. Peter Gulick moved to Lansing. The correct year was 1985.

(This story was updated at 10:11 a.m.)

Among the memories burned into Maxine Thome’s memory of the early days of the HIV pandemic is visiting one of her counseling clients in the AIDS Ward at Lansing General Hospital.

Thome, a lesbian, was among the first to actively support those living with the virus. She volunteered as a social worker, providing therapy for people with the disease then thought invariably fatal. Thome’s client was one of many with the bizarre and baffling opportunistic infection, which takes hold among the sick after the virus has eaten up the immune system.

Thome was ordered to “gown up” with a mask, gloves. She felt alien as she entered his room.

“I just remember he looked so small in that bed,” she said. “And I felt so much like an object rather than a person. I said to him: What do you need? And he said: A hug.”

Thome shed her gown, gloves and face mask.

“And we hugged. That’s a moment that will never leave me because people were still considered to be untouchable,” she explained. “And it seemed to last forever.”

This was HIV in the mid-‘80s. The virus, now widely believed to have arisen from a chimpanzee virus in Africa at the turn of the 20th century, came to Ingham County with the same vengeance it did in the nation’s coastal cities — along with the same stigmas, social isolation and fears that it carried to New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. It was a brutal disease.

Dr. Peter Gulick arrived in Lansing in 1985 after a residency at the Cleveland Clinic, where he studied oncology and infectious disease. He came to Michigan State University to teach and treat cancer and other diseases, including HIV. He had already had similar experience in 1982 with the strange new disease that was slaughtering young gay men with unexplained and catastrophic immune collapse and a host of infections that took advantage of their weak bodies.

His first years working at Lansing General Hospital’s AIDS Ward were “horrible.”

“When people with HIV were admitted, they’d put yellow tape on the doors. Food was left outside the door. People were gowned up like spacemen in treating patients because of the fear,” Guilick recalled. “It was just horrible because of the fear.”

In 1983, Suellen Hozman was a nurse working in infection control at Lansing General Hospital, where McLaren is now on Pennsylvania Avenue. She met Ingham County’s first two people diagnosed with AIDS and grew particularly close to one of them, according to the history of the Lansing Area AIDS Network.

She saw firsthand the fear and isolation that patients experienced, just like Gulick and Thome.

By 1985, both patients were dead and Hozman was teaching the hospital staff. It was clear to her that people living with HIV or an AIDS diagnosis were in need of far more than medical care. They needed support.

Thome and Doak Bloss, a figure in community theater, saw a news story about Hozman and reached out to her. They had one question: What do you need?

It was the beginning of not only the Lansing Area AIDS Network, but of the countywide and local community response to the strange and scary new disease that was ravaging the nation.

HIV by the numbers

Symptoms of the disease were first reported in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly publication. Dr. Michael Gottlieb, a physician in Los Angeles, reported on the cases of five previously healthy homosexual men who had developed pneumonia. Their immune systems were profoundly compromised. And most of them harbored a condition called cytomegalovirus, a herpes virus known for causing a mono-like illness in healthy people. It was June 5, 1981.

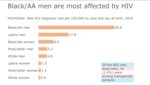

The next four cases Gottlieb would see in Los Angeles were in people of color, he told PBS’ “Frontline” a decade ago on the 30th anniversary of the disease. The first five cases he reported were white. Nationally and statewide, this racial disparity would continue to the present day.

The epidemic can be told in numbers. In 2018 — the most recent data available from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services — Black men had a new HIV diagnosis rate of 45.6 per 100,000 Black men in Michigan, while white men had a rate of just 4.8 per 100,000. Black women had a rate of 8.9 infections per 100,000. White women were tracking at below one infection per 100,000 people. The racial disparities were statistically clear.

Thousands of Michiganders have died from the disease since 1981. Today, at least 16,306 Michigan residents are living with the virus, with more than 10,000 cases in southeastern Michigan. An estimated 13% of those people are unknowingly living with the virus.

One of every 10 people diagnosed with HIV in Metro Detroit has never been linked to care — including an opportunity to access antiviral medications, which is similar to the rest of the state. Of those undergoing treatment, about 44% weren’t connected until 30 days after their diagnosis.

Outside of the Detroit area, 92% of those in care have an undetectable (or suppressed) form of the virus. In Metro Detroit, 88% of those in care have achieved an undetectable viral load.

COVID-19 has delayed reports on the status of HIV at both the county and state level. The most recent data from 2018 shows 445 people knowingly living with HIV in Ingham County. Eaton County has 91 people who know they are living with HIV and Clinton has 43. Officials estimate there to be more than 100 people across all three counties who don’t know they have the virus.

The good news is that living with HIV is no longer the death sentence it was until the early ‘90s. The advent of effective medications means that a person living with HIV is expected to survive the same life span as a person without the virus. Drugs stop the virus from replicating.

Medical science has determined that a person with an undetectable virus is unable to transmit HIV to another person during sex. Science has also discovered that using one of the HIV medications by people who are at risk of contracting HIV can prevent them from acquiring the virus through sex. That intervention is called Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and is thought to be up to 99% effective.

Despite these interventions, data from the state shows that 88% of people who know they are living with HIV in Ingham County are linked to medical care and, of those, 91% have an undetectable viral load. In Eaton County, 90% of people who know they are living with HIV are receiving medical care, but only 87% have an undetectable virus. In Clinton County, 93% are undergoing treatments for the virus in medical care, and 90% of those are undetectable.

Because the disease was first reported in sexually active gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, it was initially referred to as Gay Related Immundeficiency, or GRID. The new syndrome began manifesting as a host of bizarre and aggressive infections with telltale purple lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a skin cancer associated with older men of Mediterranean descent.

Initially, people diagnosed with HIV were given a life expectancy of no more than two years.

When the disease began appearing in people who had blood transfusions and in the children of women who injected drugs, the disease was renamed AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Regardless of its name, it was deadly and no one knew quite what was causing it.

It would take scientists three years to identify the retrovirus responsible for the new syndrome. And even that discovery, announced in 1984, would be overshadowed by scientific scandal as Dr. Robert Gallo would take credit for the discovery, but a review of his work would determine the virus was the exact same genetic virus as the one discovered by the French in 1983.

Scientists brought them together and renamed the virus HIV — human immunodeficiency virus.

A test for the virus was approved by the FDA in 1985, but medical science could offer no intervention to slow or stop the relentless war that the tiny package of RNA would wage in a human body, slowly destroying the immune system and allowing other bacteria, fungus and viruses to overwhelm and ultimately kill its human host. There was no cure at their disposal.

Bias in the beginning and now

There was barely a governmental response to the pandemic. After all, the virus was mostly impacting gay and bisexual men and people who injected drugs. This was the era of President Ronald Reagan — the zenith of power for the religious right and the birth of the war on drugs.

Reagan himself would not give a speech about the disease until 1987, and even then, he would only mention it in passing and in sparse selection of budget priorities. The Reagan administration had abandoned entire swaths of America to the virus.

Queer communities rose up to fight the virus and support those who had become ill. Curtis Lipscomb, executive director of LGBT Detroit, was living in New York City when the radical protest movement AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power arose from the communal grief and rage.

The movement staged highly theatrical protest events, including die-ins, targeting high profile sites like St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Wall Street and even the “CBS Evening News” with Dan Rather. They wanted to make sure the plight of gay men — most of whom were white — was known.

As a Black man living in the most populated city in America who was aware of the virus’ impact in his community, Lipscomb was thankful for ACT UP but he didn’t feel part of the movement.

“I knew at the time that what they were doing was important to me, for me,” he said. “But it was not a space I felt welcome in.”

Lipscomb talked about how queer spaces — discos and sex clubs — were racially segregated in New York and in Detroit. Menjo’s, a popular night club in Detroit, was infamous for requiring Black patrons to present multiple forms of identification to get in. And once inside the bar, Black men were largely relegated to an isolated corner of the bar.

“It was the Black corner,” Hank Millbourne, a Black man who helped run AIDS Partnership Michigan in Detroit, said. Millbourne recalled community members referring to the Menjo’s area.

HIV education materials that circulated in Michigan in the ‘80s predominantly featured white men.

“It didn’t speak to me,” Millbourne added. He and his team recreated the educational materials to speak to Black and brown communities in Detroit.

In the late 80s, when AZT was approved as the first drug to treat HIV, it had not been tested thoroughly in the Black community. One of the unforeseen side effects included turning fingernails and toenails black. Millbourne recalls his friends in the late ‘80s asking him why he was speaking to certain Black men in the bar scene.

He was told they had “the package”— as evidenced by the Black nails on their hands. Millbourne said he was unclear at first that the package meant HIV.

In 1987, Renee Canady landed her “very first professional job out of college” at the Ingham County Health Department as the county’s first AIDS educator. The position was brand new. She was told to “figure it out,” on how to raise awareness and education about HIV.

“As a Black straight woman, the framing and the narrative back then wasn’t really anything I perceived as impacting me or my community. When I saw this opportunity and started reading and learning about what was really going on I was like: This is terrible — not just for these people they are shaping the narrative around, but for a lot of people, for all of us.”

Canady would go on to helm the department as the county’s health officer and now leads the Michigan Public Health Institute. Racial disparities are a common point of concern in funding and structuring programs to address public health statewide. HIV laid bare the racial inequities in healthcare and access that plague Black communities locally, Canady explained.

Meeting local needs

Hozman told Bloss and Thome what was needed was support. People with the disease were unable to complete basic life tasks like grocery shopping or caring for their pets. The disease left them feeling afraid. Their community often turned its back, leaving them isolated and alone. The people living with the virus needed, more than anything, some human compassion.

Bloss had just ended a 10-year relationship with his college boyfriend. The two were popular in local theater groups. They were the “acceptable” gays, he joked — the charming theater couple.

He said he was looking for something to do as he rebuilt his life after he broke up with his boyfriend. Assisting those with AIDS seemed like an opportunity to get to better know the gay community and help.

Bloss threw himself into the work of supporting people living with AIDS — driving them to appointments, grocery shopping for them, assisting them in getting to doctor’s appointments. It was called the Buddy Program, which paired volunteers with people living with AIDS.

At the time, in 1985, there were only 10 people known to be living with AIDS in Ingham County, he said. As he tried to raise awareness, he faced pushback from the gay men’s community, which pointed to how few cases there were. There was still denial, he said, still “a lot of fear.”

Meanwhile, Thome was doing the same thing as Bloss. It became obvious quickly that the Buddy program needed funding and a way to handle financial donations from people unwilling or unable to join. The bylaws for the Lansing Area AIDS Network were written, she recalled, over a meal in El Azteco.

Closing a chapter

For 18 years, Jake Distel has helmed the Lansing Area AIDS Network, shepherding fundraising, grant writing, prevention programming and medical case management for people living with HIV. Like so many others, he said he watched his friends die from the virus in the 80s and 90s.

While they lived in Toledo, his partner, Jon Hoffer, was diagnosed with HIV in the late ‘80s. For a time, Distel wrongly presumed he too had the virus, and both men took AZT to stave off the effects. Hoffer died in 1996 from AIDS, just months before the miraculous HIV cocktails were released to patients.

Distel recalled how the small newspaper in his hometown refused to run Hoffer’s obituary because it explicitly said he died of AIDS. He said Hoffer’s mother took the paper to task and shamed them into running the memorial.

He also recalled his first real interaction with a person living with HIV via his friend Dennis Michaels, a popular female impersonator in Columbus. Distel and Hoffer would travel from Toledo to watch his performances. He recalls Michaels’ last appearance on stage.

“He performed in a wheelchair,’ Distel said. “Everyone knew what was going on at that point, but he did it. He rolled out onto the stage to a standing ovation.”

Even after Hoffer and Distel moved to Washtenaw County, the couple would still travel to Toledo for Sunday brunches. It was a community response that grew out of the isolation and rejection of queer identities in the AIDS crisis. The families of many of the men who died didn’t want to acknowledge they were gay. Their identity was hidden. To deal with that, the local bars began hosting Sunday brunches, for free, as a memorial to those who lost their lives to the virus.

Millbourne recalls during the late 90s, the Black queer community would host parallel memorials for those lost to AIDS in which “We could remember people completely,” he explained.

And in Ingham County, Thome and others created the “Remember My Name” project, held on the steps of the Capitol on the mornings of gay pride marches. The names of people who had died of AIDS would be read. Their names were inscribed on ribbons and affixed to sticks.

Those ribbon-streaming sticks would lead the march, but by the mid-’90s there were too many names to read in the five hours before the march.

As Thome recalled the early days of the pandmeic, she thought of her time serving on the board of the Michigan Organization for Human Rights, one of the state’s first LGBTQ organizations.

“I just think back to those times, and it seems like every month, another person was gone,” she said. “It was like the table was emptying. It was. People were just gone.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here