State Rep. Sarah Anthony is tired of seeing Lansing families take a pass on Lansing schools.

Every year, the parents of thousands of children who live within the Lansing School District — for one reason or another — decide their kids are better off attending classes outside of the city and away from its public schools, according to Ingham Intermediate School District records.

As an Everett High School student in the late ‘90s, Anthony didn’t think much about why some of her neighbors were deciding to attend other districts. But after graduating college and getting into politics, the declining reputation of her hometown district started to strike a personal chord.

“I really came back with different eyes after college,” Anthony said. “I started to see how people perceived our school district and how for so many people, Lansing schools just weren’t even an option for them. I saw how the buildings were just falling apart. And to be honest, it all really ticked me off because it sent out a clear message that we didn’t care about our kids.”

Last fall, the LSD recorded about 2,900 Lansing area students who opted not to attend the city’s public schools despite living within the district boundaries — instead picking a neighboring district or another nearby private or charter school. Only about 400 students opted in last fall.

Anthony said the reasons for the ongoing exodus are numerous: For some parents, it’s more convenient to drop off their kids elsewhere on the way out to work; some families pick the schools with the highest test scores, the best sports teams or the most extracurricular offerings.

But for others, the reasons for leaving Lansing are a bit more obvious, Anthony explained. Nineteen of the district’s 25 school buildings were built before 1970. And nine were rated in “poor” condition in a recent facility assessment. Put simply: The schools have seen better days.

“The condition of some of these buildings was plainly telling these families and these students that they weren’t worth the investment — that the community didn’t care about them,” Anthony said. “So, when I saw another opportunity to invest in our schools, of course, I’m here for that.”

Last month, Anthony and Dean Transportation President Kellie Dean stepped up to serve as the volunteer campaign co-chairs of a bond proposal that aims to infuse another $130 million in tax revenue into the school district’s coffers to help rebuild four elementary schools, renovate Everett High School and ensure that every classroom in the district has working air conditioning.

The proposal will be on the ballot on May 3 for voters in Ingham, Eaton and Clinton counties who live within the district boundaries. Absentee ballots are set to be sent out this week — giving voters the task of deciding whether or not the district is worthy of more taxpayer cash.

“Any opportunity I have to be a cheerleader for Lansing schools, I’m absolutely going to do it,” Anthony said. “This one is a hands-down, no-brainer. It’s about investing in new schools, improving student comfort and refreshing Sexton High School — and everyone will benefit.”

What’s on the ballot?

For the third time since 2016, the Lansing School District is turning to local voters to help drive the district into the 21st Century — even if it’s now more than two decades behind schedule.

The proposal would enable the district to borrow $129.7 million, pay off and refinance old debt and reissue bonds, all without increasing local tax rates, for three primary purposes: Demolish and rebuild four elementary schools; equip every classroom in the district with air conditioning and make some significant renovations (including a new auditorium) at Sexton High School.

“That’s really it. That’s the cool thing about this bond,” said Superintendent Ben Shuldiner. “A lot of times, school districts will try to throw in a little bit here or a little bit there. With this proposal, it’s so easy to understand what we’re asking for: It’s four buildings, air conditioning and some love for Sexton — nothing else. It’s really all about creating a better learning environment.”

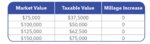

If the measure is approved next month, homeowners within the district would continue to be taxed 0.58 mills — or $0.58 on each $1,000 of taxable value — for a cumulative annual millage rate of 1.88 mills. If it fails, residents would see their tax rates decreased by the same amount.

“No new taxes. That’s one of the biggest selling points,” Anthony added. “It won’t increase the debt millage, yet it’ll lead to a massive investment for local schools. And everything in our community is connected to education. It’s economic development. It’s arts and entertainment. Schools attract people into the community. That creates new businesses. That builds jobs. It’s not just tax giveaways and incentive packages that make mid-Michigan attractive. It’s schools.”

Which elementary schools will be rebuilt?

Four of the district’s oldest elementary schools will be demolished and rebuilt (though likely in reverse order) by 2030 if the proposal passes next month, Shuldiner explained. The first project — and the top priority — will be rebuilding Mt. Hope STEAM School, the district’s oldest operational elementary school, which houses about 250 fourth-, fifth- and sixth-grade students.

Afterward, and in no particular order, the district plans to use the bond cash to build “21st Century” replacements for Willow Elementary School, Lewton Spanish Immersion and Global Studies Magnet School and the Sheridan Road STEM Magnet School. Shuldiner said each of the schools would be rebuilt just a few hundred yards away from the existing buildings, which would then be torn down only after the new buildings are ready to fill classrooms with students.

Each project is estimated to take 18-24 months, with some overlap, over the next 6-8 years. The total reconstruction costs are set to tally to almost exactly $100 million — about $22.1 million each for Mt. Hope and Willow; $24.3 million for Sheridan and another $31 million for Lewton.

Mt. Hope — the oldest of the bunch — was built in 1948, back when President Harry S. Truman was still in office. Willow was constructed in 1952. Sheridan and Lewton were built in 1954 and 1957, respectively. Combined, the schools tracked a total enrollment of 877 students last fall.

An assessment outlined in district records pegged those four buildings as having some of the poorest conditions of any others in the district — all scoring below 60%, which is usually low enough to warrant an “F” in the standardized testing world. Those same assessments found that renovations at the “end-of-life” elementary schools would be more costly than a total rebuild.

All of them would be replaced with “brand new, 21st Century” schools that will be “purpose-built” with “age-appropriate spaces,” modern technology, new furniture and an overall more inviting atmosphere — with plenty of natural sunlight, Shuldiner said. The idea: Keep the facilities updated to match more effective instructional models and keep students comfortable in class.

“Every morning, thousands of students who live in Lansing leave Lansing to go to school in other places. One of the main reasons they do that is because of the school environment and the school buildings in other districts are in great shape,” Shuldiner said. “I think we owe it to the students of Lansing to bring them into a better environment and make them more comfortable.”

With state funding for public school districts set at $8,700 per student, the families who chose to send their kids outside of the Lansing School District last fall also effectively took with them about $21.5 million that would have otherwise been rolled into the district’s budget this year.

It’s not the primary objective, but building new schools can help lure them back, Shuldiner said.

“I get the argument,” added School Board President Gabrielle Lawrence. “You want your child to have the best. I also want my kids to have the best. I want them to attend schools with updated facilities and cutting edge technology. That’s exactly what we’re trying to do here in Lansing.”

What about the other $30 million?

Studies have long shown that indoor air quality is directly linked to health outcomes and student academic performance. It can also play a crucial role in mitigating against the spread of viruses — a lesson that was repeatedly learned over the last two pandemic-filled years in Lansing.

Still, district officials estimate that less than one-third of classrooms across the district currently have functional air conditioning — which can also make for some sweaty and uncomfortable learning environments for students, particularly as the spring semester drags on into late May.

City Council President Adam Hussain — who also teaches social studies at Waverly Middle School — said the physical learning environment is a critical component to his students’ ability to succeed. Cleaner air and cooler temperatures can simultaneously help to increase attendance rates, boost test scores and lead to more student engagement in the classroom.

So, about $19.1 million of the bond proposal cash will be earmarked for the installation of new air conditioning systems to cover every classroom in Lansing, according to district literature. If the bond proposal passes, Shuldiner hopes to have the work finished within the next 3-5 years.

“A lot of that centers on things that people don’t necessarily think about,” Hussain said. “The air quality, for example, is so important. Temperature is important. I know this not only from reading the studies, but from working with my own students. This is a chance to invest in schools, ensure the physical environment makes sense and create that learning opportunity.”

Lawrence said the districtwide air conditioning overhaul may also help open the door to more summer learning opportunities, which are currently unbearable in the warmer months. That includes the possibility of moving to a year-round “balanced” calendar, she told City Pulse.

“Maybe in the future we can look at it, or maybe that’s just wishful thinking,” Lawrence added. “But as a parent of a four-year-old boy who is starting school in the fall, I know next summer is going to be challenging and this could create an opportunity to consider something different.”

Building on recent renovations at the city’s two other high schools from the last bond proposal in 2016, district officials have also targeted J.W. Sexton High School for about $10.9 million in renovations — including about $5.8 million in air conditioning upgrades, $2.1 million for a new auditorium and another $2.6 million for new ceilings, paint, window shades and other fixes.

If the bond proposal passes, Shuldiner hopes to have those renovations done within five years.

Déjà vu?

In May 2016, Lansing voters approved a $25.2 bond proposal for the school district by a margin of about 61%, as well as a slightly less-popular sinking fund proposal in May 2019 — a three-mill property tax increase for 10 years that’s estimated to draw in another $73 million.

Since then, more than $120 million has now been spent on various improvements at several school buildings — including renovations at Everett High School, new furniture and updated technology in every building, and a newly rebuilt Eastern High School and athletic complex. The latest sinking fund proposal has also helped pay for upgrades like new roofs and utility systems, security upgrades for front entrances and more as part of the “Securing the Pathways” plan.

This year’s bond proposal has been billed by district officials as a “continuation” of those improvements — a necessary move that will enable the district to spread infrastructural love across the city. And without increasing the local millage rate, it would also still keep the school district’s capital improvement millage rates set among the lowest in the Greater Lansing region.

Lansing Councilman Peter Spadafore, former president of the district’s Board of Education, said the deteriorating state of the district’s buildings is the result of years of neglected maintenance, which was only compounded by a dwindling stream of tax revenue — at least before 2016.

“The voters are always generous to the school district when asked. We just didn’t do a very good job of asking them on a regular basis,” Spadafore said. “That kept our taxes lower compared to other districts in the region, but the physical environment really suffered.

“When you look at brand new elementary schools going up in neighboring districts, you have to wonder whether sometimes parents make decisions based on infrastructure,” Spadafore added. “It might not be the primary factor, but it certainly wouldn’t hurt to remove that from the equation.”

Added Anthony: “I don’t think it’s out of the realm of possibility that students in Grand Ledge or Mason or Holt or East Lansing will see these improvements and think differently about Lansing.”

Spadafore, Hussain and Lansing Mayor Andy Schor have all voiced support for the proposal — billing it as a crucial step in ensuring the district is prepared for another century of learning.

“Our children need facilities that reflect the quality of their education in schools,” Schor said. “Updating the infrastructure of our schools is important for our children’s education and benefits our community, and this millage proposal allows our city to do this without a millage increase.”

And even for voters who don’t have children, the peripheral benefits of creating higher quality schools is expected to pay broader economic dividends for the region, Shuldiner contended.

Decades of economic research shows a proven connection between the perception of high-quality schools and a region’s ability to attract business investment — which in turn could trickle down to create more jobs, raise property values and create a greater “quality of life.”

“Most important of all is the impact Lansing’s schools have on our overall economy,” he explained last week. “We produce much of the talent that keeps our employers thriving, and every operating budget dollar we divert from the classroom to pay for capital needs has a trickle effect in terms of what future Lansing graduates know and are able to do in their work.”

If the ballot proposal fails, district officials have published warnings about a potential need to reconsider their “financial picture” and draw down instructional resources to cover maintenance.

It’s a path that hasn’t been mapped, and one that Shuldiner hopes he won’t have to navigate.

“The school district will always do everything in its capacity to bring the best education possible to our students,” Shuldiner said. “However, if the bond doesn’t pass, it will make it that much harder.”

How do I vote?

The Lansing School District includes properties in Lansing and certain parts of East Lansing, as well as DeWitt, Lansing, Delta, Windsor and Delhi townships. To vote at home, register to vote absentee online or by mail by April 18 and then return a completed ballot by May 3. Voters can also register and vote in person on Election Day. Polls will be open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. Absentee ballots returned within two weeks of Election Day should be hand delivered to avoid potential delays. Visit lansingvotes.com or michigan.gov/vote for more detailed information.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Other items that may interest you

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here