The fight over the separation of refugee families at the United States border is part of a bigger picture that has Lansing-area refugee support workers deeply concerned: the sharpest drop in refugee resettlement, nationwide and in greater Lansing, in half a century.

Judy Harris, director of the refugee resettlement program at St. Vincent Catholic Charities, which resettles families and adult refugees, said refugee resettlement in the US “has almost completely stopped at this point.”

“We used to have a very robust refugee resettlement program here in Lansing,” Harris said.

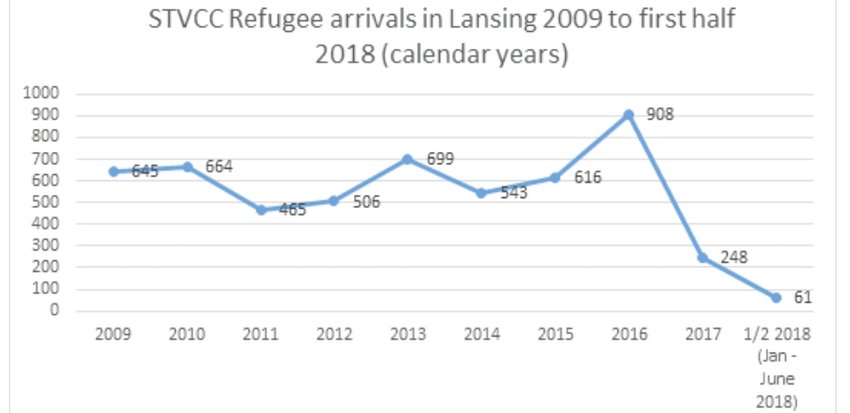

In the years leading up to 2017, St. Vincent Catholic Charities resettled about 600 people a year in Lansing and mid-Michigan. With 2018 about half way over, about 118 have been resettled.

“A lot of stuff went on last year — executive orders, travel bans, everything went up and down for a while,” Harris said. She attributed the drop, in part, to federal staffing reductions at embassies and other agencies that handle refugees.

“People aren’t being interviewed and the paperwork isn’t being processed, and so there’s nobody coming,” Harris said.

Harris also cited increasingly stringent vetting procedures for refugees. “The kinds of questions they’re asking people, they aren’t necessarily able to answer,” she said. “They have to provide names and addresses of all relatives anywhere in the world, not just in the U.S. In a war situation, it’s complicated to know if anyone is alive, let alone where they’re living.”

For fiscal year 2018, President Donald Trump capped the number of refugees who can resettle in the United States at 45,000, the lowest number since the president was given authority to set the cap in 1980. (The previous low was Ronald Reagan’s cap of 67,000 in 1986.) Meanwhile, the number of refugees in the world is skyrocketing to new heights. The United Nations estimated 68.5 million forcibly displaced people in the world in 2017, of which 25.4 million are classified as refugees.

The disparity between America’s closing door and the growing multitude outside also worries Shirin Kambin Timms, coordinator of the Refugee and Immigrant Resource Collaborative, a network of 50 organizations serving the refugee and immigrant community.

“The severe decline in refugee resettlement is part of a larger pinch on all immigration to the United States,” Timms said. “We are concerned about the messaging surrounding immigrants and refugees.”

The “big pinch” involves a lot of fingers. “A full sweep of changes is both proposed and underway,” Timms said, including “proposals to reduce or eliminate family reunification efforts, the Diversity Lottery, US border practices and more.”

Refugee support organizations are struggling to keep funding constant as federal policy, and refugee numbers, spike up and down.

“They are experiencing whiplash from all these executive orders,” said the Rev. Kit Carson of All Saints Episcopal Church, a donor to St. Vincent Catholic Charities. “And because they receive funds to resettle refugees, when the flow of refugees pauses or is cut off, they lose funds. They live in a state of continual uncertainty.”

Harris said St. Vincent Catholic Charities is keeping staffing levels up by concentrating more on working with refugees who have already resettled in recent years. The charity offers classes in small business development, classes on buying a house, financial literacy and other life skills, computer literacy and expanded English classes.

“Refugees are good for Lansing,” Harris said. “We get calls all day long from employers saying, ‘Do you have any new arrivals?’ In our communities, our schools, this has been a really successful program, so we want them to start coming again, and we’re hopeful.”

The fate of over 2,000 children separated from their parents at the U.S. border under the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy is still uncertain, but it will likely have a disparate impact on Michigan, where two organizations have contracts with the federal government to accept separated immigrant children: Grand Rapids-based Bethany Christian Services and Samaritas, a nonprofit with 70 program sites in 40 cities, including Lansing.

“There are only a few foster programs around the country, about 20, so for Michigan to have two is kind of a big deal,” Harris said.

Samaritas has had a program for unaccompanied refugee minors, or URM, since 2001, according to spokeswoman Lynne Golodner.

“We have URM foster parents in Lansing and throughout the state,” Golodner said.

But Golodner was careful to distinguish between such programs, which help unaccompanied refugee minors find long-term foster care, with the kind of program that would help children separated from their parents at the border.

Golodner said Samaritas does not yet have a transitional foster care program — a temporary program for children until they are reunited with their parents.

“We had it until 2015 but discontinued it because there was no need at the time,” Golodner said. “Samaritas has no children from the border.”

The national Office of Refugee Resettlement solicited proposals last week from organizations certified to do transitional foster care. Samaritas submitted a proposal to resettle 50 to 60 unaccompanied refugee minors, but it hasn’t been approved yet.

“Until it’s approved, no one knows what will happen,” Golodner said. “If and when we get the green light, we will accommodate children who were separated at the border.”

On the west side of Michigan, Bethany Christian Services in Grand Rapids has admitted over 80 children into its foster care program since the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance policy was implemented last month.

The practice is not popular with opponents who charge Bethany with kidnaping kids for profit. (Bethany has not put any of the children up for adoption, and it’s not known whether they will be reunited with their parents.)

Protesters picketed Bethany’s Grand Rapids offices June 20, charging that the organization is profiting from an inhumane policy and demanding that it end its contract with the federal Office of Refugees.

Bethany also has a history of working against reunification or adoption to parents who are non-Christian, LGBTQ or legal medical marijuana patients.

A video posted Monday by attorney Susan Reed of the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center raised another issue: legal representation for unaccompanied minors.

“Michigan is one of the biggest states for federal foster care, and we represent all of those children in those foster care programs,” Reed said.

Staff attorneys at MIRC are accustomed to representing young clients who got to the U.S. on their own, not children under 12. Reed said that the family separation policy, “a new policy that has been chosen by the administration,” has brought them new clients who are “much younger than the clients our program is resourced to serve.”

While trying to find their parents, MIRC staff is trying everything, from crayons to puppets, to help traumatized kids tell their stories.

“All of a sudden we are getting requests from people who want to give diapers or other supplies to help unaccompanied children,” Reed said. It’s a great start, she said (with a slightly weary tone in her voice), but it’s important to “seek justice for immigrant children, not just charity in the form of diapers.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here