Twice a month, the coronavirus develops a new mutation. Some of those mutations are harmless. Some are more ominous, like the B.1.1.7 variant originally identified in the U.K., the B1.351 variant originally found in South Africa and the P.1 variant which was identified in Brazil.

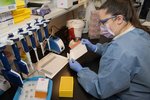

Since last March, even before COVID-19 was confirmed in Michigan, two women have led the state’s efforts to study the genetics of various samples of the virus — and other diseases — and have successfully sequenced about 9,000 individual virus samples from Michigan residents.

But sequencing those viruses takes time — often too much time — for communities to get ahead of them. The recent outbreak at Grand Ledge High School last month is a perfect example: A keen-eyed staffer noticed a quick pace of transmission among the basketball team and sent samples to the state lab for sequencing. Meanwhile, public health used traditional quarantine and isolation protocols and was able to lock down the cluster and slow its spread.

Three weeks after submitting the samples, state health officials confirmed Grand Ledge had the variant known as B.1.1.7. By then, many of those infected had already finished quarantines.

There’s a reason it takes so long, said Marty Soehnlen, director of the infectious disease division at the state Bureau of Laboratories. She oversees the sequencing of those variants.

It’s a complicated process, and she has a favorite analogy to describe it in simpler terms.

“If I take the entire volumes of the encyclopedia and I toss them in a wood chipper and it spits all of that paper out back in, I’m having somebody sit there with a glue stick and have to put all of it back together in the correct order,” she explained. And when the genome of the virus is sequenced out, it produces tens of thousands of codes representing genetic combinations.

Heather Blankenship, bioinformatics and sequencing section manager at the lab, said that the process of “putting it back together,” can take two days or more. And once it’s back together, the genome has to be read, analyzed and tracked based on mutation variations in certain regions.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here