“I often dream about floods and flood zones, and I do feel this urge to return,” the artist said at Friday’s exhibit opening.

In Mendel’s portraits, life-sized flood victims from five continents stare straight at the bone-dry viewer, folded at the neck, waist, or knees by an inexorable water line. Above the line is normality; below is murk.

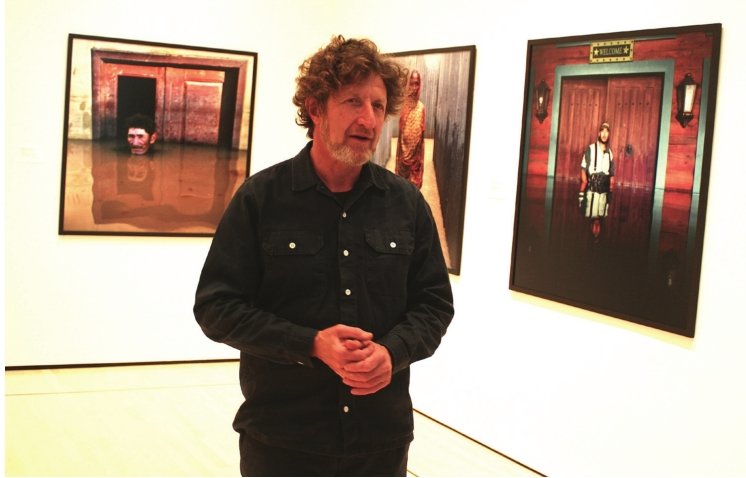

Mendel often talks about his work at climate change conferences, but he’s an artist, not a journalist. At Friday’s event, he talked like a man caught in an aesthetic undertow.

“People say to me, ‘It must be so difficult and painful and traumatic,’” he said. “The truth is, as a photographer, as an artist, I’ve come to love being in flood zones.”

Mendel started documenting floods in India and the United Kingdom in 2007. Since then, he has photographed floods in Pakistan in 2010, Thailand and Australia in 2011, Nigeria in 2012 and South Carolina in 2014.

“There’s something about that environment that I find immensely compelling, visually,” he said “Everything is reversed. Nothing is where it was meant to be. The light is changed by the water.”

Mendel isn’t sure whether his work is evidence of climate change or a metaphor for it. Water seeps into the mind as surely as it covers the planet, and that makes Mendel’s photographs hard to shake off. As you look around the gallery, the ever-present water line cuts as cleanly as mathematics across cultures and countries. It would be hard to find a more dramatic metaphor for — or evidence of — humanity’s common lot.

Broad Art Museum curator Caitlín Doherty, who curated the Mendel exhibit, has been haunted by Mendel’s images since she first saw them in 2007.

“These people are from different countries, entirely different socio-economic and cultural situations, but they are all united by their vulnerability,” Doherty said.

The beauty and gravity of the subjects’ faces stubbornly defy the chaos around them. “The photographs obey all the rules of conventional portraiture, but the environment is quite strange,” Mendel said.

The exhibit is divided into two parts. The first is a selection of Mendel’s “Drowning World” photographs, a few of them never before seen, along with a halfhour video of people mournfully wading, gingerly rowing and playfully backflipping through flooded streets in cities around the world.

The second part of the exhibit, the “Watermarks” series, brings Mendel’s work into a new phase, seen for the first time at the Broad. The gallery is hung with flood-damaged snapshots that are “massively amplified,” in Mendel’s words, to the size of posters.

Fishing ordinary family photos from flood areas, Mendel found that wedding pictures, high school portraits, vacation snapshots and other pictures had turned into semi-abstract mosaics of patterns, colors, faces and backgrounds.

A vitrine in the center of the gallery contains a pile of the originals. Mendel has collected about 400 of them.

“They’re muddy and destroyed, but yet beautiful,” Doherty said.

As in the “Drowning World” photographs, a blatant metaphor all but jumped from the blotchy, patchy images. Mendel was fascinated by the role of chance in saving parts of the images and obliterating others. The capricious waters dealt the same with the photos as they had with people.

“They work on a level I’m not used to dealing with,” Mendel said. “I don’t fully understand why I’m so drawn to them. “ At a question-and-answer session after Friday’s talk, Mendel seemed familiar with the accusation that he is exploiting his subjects and aestheticizing tragedy. He said he’s well aware of the issue of subject consent, appropriation and “the gaze.” But he seemed content to leave the question open and continue to do what he does.

His interactions with subjects, he explained, vary according to the circumstances. Sometimes he pays people 30 dollars to lead him to their flooded homes and let themselves be photographed. At other times, he doesn’t get consent, but he appeared comfortable with his methods.

One flood victim, he said, refused his money. “I want you to show the world what’s happened to us,” she told him.

“As a curator, you get a gut feeling about the genuineness of work,” Doherty said in the artist’s defense. “I felt that four years ago, and it haunted me ever since. I now know that initial gut feeling was correct.”

Doherty found it “particularly powerful” that the people in Mendel’s portraits are named and not anonymous victims.

Mendel pointed out that in 2008, at the same time Hurricane Sandy hit North America, massive floods in Nigeria killed 500 people and left almost an eighth of the country under water. Although the disaster was worse than Sandy, there was very little press coverage. Mendel’s Instagram feed was among the few outlets to give the world a glimpse of the disaster.

“They want what’s happened to them be deeply witnessed, and that’s what I do,” he said.

“Gideon Mendel: Drowning World”

Open through Oct. 16 FREE Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum 547 E. Circle Drive, East Lansing (517) 884-4800, broadmuseum.msu.edu

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here