There’s no question if he had lived, Andrew Bourdain would’ve made his way to the land of the “good berry,” just as the Anishinaabeg had centuries ago in search of a land where food grows on water.

In the oral tradition of the Anishinaabeg there exists a prophecy that the people would follow a sign moving inland to avoid the long boats of the European invaders. The prophecy said the people would know when to stop when they found food growing on water. The Great Lakes basin would be one of those areas. The prophecy also predicted if the indigenous population did not move they would be destroyed. Thus began the great migration west.

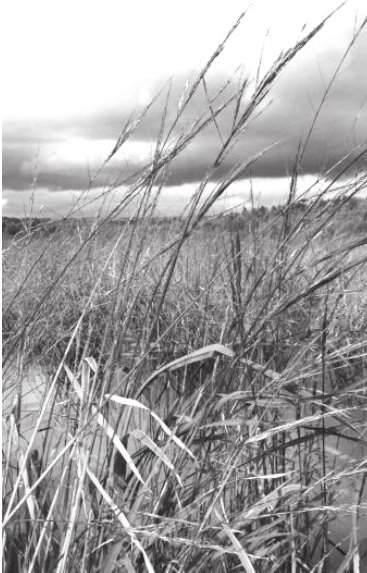

Michigan’s lakes, rivers and marshes were once rich with Manoomin, or wild rice. For the Anishinaabeg, Manoomin would become the source of both spiritual and physical sustenance.

In her new book, “Manoomin: The Story of Wild Rice in Michigan,” Lansingarea biologist and forager Barbara Barton writes about the vast areas of Michigan rice beds and their ultimate demise due to the arrival of European colonizers and their shortsighted practices.

In the name of progress, Michigan’s once pristine waterways became seen as a path to riches. Forests were clear cut, wetlands drained, rivers dammed and muck farming instituted.

Barton also writes about the dredging by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the many pollutants that were dumped in the waterways: “Manoomin was being cut, dredged, poisoned, smothered and drowned. It didn’t stand a chance.”

Barton lists the hundreds of sites in Michigan that were home to rice beds. Sadly, time marches on and canoes gave way to jet skis. Today, according to Barton, there is only one remaining rice bed in Michigan, but Michigan’s Indian tribes have begun wild rice restoration.

In a lifetime spent foraging, Barton said she knew little about Manoomin. In 2008, her desire to learn took her the Keweenaw Bay Indian Casino, where she met Roger LaBine, a member of the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians and an acknowledged expert on wild rice.

One thing Barton had learned through foraging was patience and it paid off since LaBine was five hours late for the meeting.

In the preface she writes, “Thank goodness I am blessed with patience because the relationships that developed from that meeting with Roger changed my life.”

LaBine would introduce her to not only the practical aspects of rice growing and harvesting but also to its important spiritual significance to the Anishinaabeg.

In her book Barton connects directly to the Anishinaabeg by incorporating introductions to each chapter written by her “tribal friends.”

She also sought out recipes like wild rice with cinnamon and raisins which is clearly an amalgam of cultures. She said that Manoomin is a versatile food that is high in protein, low in salt and saturated fat and can be served as a main dish, side dish or dessert. It also can be ground into flour.

Barton said “I was just smitten with wild rice, like I am with honey bees.”

Barton keeps a number of hives at her home in Lansing and at nearby farms.

She cautions those seeking wild rice to be careful, since most wild rice that is sold and advertised at roadside stands in actually what is called “paddy rice,” a genetically distant cousin to Manoomin. Even then, paddy rice can cost $5 a pound.

The book is also a practical guide to how wild rice grows and the intensity and spiritual journey of harvesting it. Today, it is harvested in the same manner as it was centuries ago with much decorum and religious ceremony that reaches back more than a millennium. Documented seeds of Manoomin have been found dating to 400 A.D.

Barton also details the previous and ongoing efforts of restoration that have been undertaken by Michigan tribes, but she is not optimistic about its long term viability.

“I’m not sure we will have wild rice 100 years from now, unless we can get it to come back,” she said.

Barton also said that the television show “State Plate,” hosted by Taylor Hicks, will be visiting her in Lansing to film a segment on how Manoomin is harvested, processed and prepared. “State Plate” focuses on state’s unique foodways.

The next subject Barton wants to write about is foraging for wild food in Michigan.

“There will be a story with each plant and our relationship with nature,” Barton said.

Book club meeting canceled The meeting of the City Pulse Book Club scheduled for Thursday has been canceled due to insufficient interest.

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here