The acclaimed Charles Pollock and Frank Cassara murals of Lansing's John Dye Water Conditioning Plant’s main lobby are not the only works stored in the Art Deco inspired building. In the plant’s basement bowels, a smorgasbord of art from over 80 years ago springs forth from dusty columns.

A section of the plant, the Cedar Pumping Building, goes back even further to its construction in 1883. Inside the building, among other water processing equipment, is a long-retired steam pump from the turn of the 20th century sitting dormant in almost a third of the upper floor. It supplied Lansing with water, and used the smokestack behind the Nuthouse Sports Grill for its coal smoke exhaust.

“We still use this pumping station as a backup for the city of Lansing,” BWL water division director Scott Hamelink said. “What you see here is all the piping that brings the water from the reservoirs and pushes it out into the system.”

Descending down into the pump building’s basement opens up to a labyrinth of pipes running in every direction. Cable carriers that look like miniature train tracks weave throughout rows of arches and pipes to their final destinations.

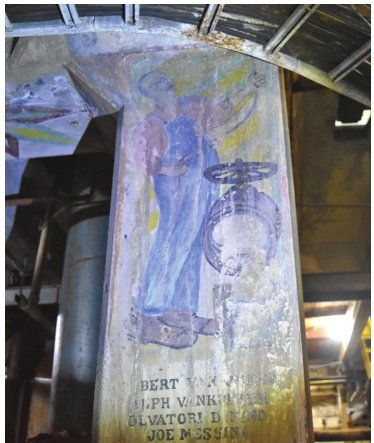

The folk art murals are condensed primarily on two sets of arches. Running through it is a massive pipe entitled “Suc. 4,” acting as a suction pipe from a reservoir.

It was all the work of one boiler operator, Clarence “Charlie” Hewes.

“He had a lot of time on his hands.

Usually those boiler operators used to take reads that took maybe five to ten minutes total. Then he probably came back down here to paint for the other 40 or 50 minutes,” Hamelink said.

Hewes had even more time on his hands because he was a night shift employee. “Our loads would go down at night and the boiler wouldn’t have to be observed during his shift as normal.”

An excerpt from Michigan State University Press’ 1978 publication “Rainbows in the Sky: The Folk Art of Michigan in the Twentieth Century,” by C. Kurt Dewhurst and Marsha MacDowell, mentions Hewes’ work and corroborates Hamelink’s statement:

“Hewes once gave the following account of the work responsibilities, which afforded him an opportunity to spend time at work painting: ‘When the load drops off after 8 or 9 at night, there’s not much to do. The only two men here are an operator and a fireman, and they can usually tell if something goes wrong by the sound.’” Under lighting, the art appears. It’s a dizzying mishmash of BWL staff rosters, art deco ornamentation, every Lansing water station, amateur poems and worker depictions.

Recognizable names like general manager Otto Eckert and chief chemist John Dye hold top positions in the archway. There is also a painting on the top of the arch of a check Hewes presumably wrote to himself for $1 million from BWL.

“We try to be sensitive to them when we work down here and try not to damage anything. But it is just the sands of time have taken their toll on them,” BWL CEO and general manager Dick Peffley said.

Appointed CEO in 2015, Peffley has worked at BWL for 42 years.

“There are not a lot of people on the board who don't know these are even down here,” Peffley said. “The water department is a division of a bigger company. I knew they were down here because I worked over here for awhile when I first hired in.”

Most BWL employees see the Charles Pollock and Frank Cassara murals as more emblematic of the company, Peffley said.

“This is a little out of sight and out of mind.” People used to know the story of Hewes’ art more, but it is still passed down occasionally, he said.

“The story stays pretty accurate. There are still a lot of people here who have been here for 40 years and we keep it original.”

Though there are many imitators with permanent markers scrawling their names next to the art, Hewes’ writing is unmistakable.

“When I start recognizing the names, I know they are the add-on stuff.”

For some BWL employees, it has become an unofficial rite of passage when retiring to scrawl their names beside the folk art.

Peffley and Hamelink recognize a few new names since their last visit to the basement.

“Look at this — 'Scott,'” Peffley said while pointing out a fresh name in permanent marker. “He just retired after being hired on in 1985. He left only about a month ago.”

Support City Pulse - Donate Today!

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here